Earlier this month, the Native American Journalists Association created what it called “a new tool” for newsrooms covering Indigenous communities.

That tool is a bingo card.

Say what?

Indulge me here as I explain what is behind the association’s purpose, which is very much applicable to Canada, particularly Vancouver and the rest of the region. Yes, the bingo card is a real thing. It’s not, however, filled with numbers, but clichés and stereotypes of Indigenous people.

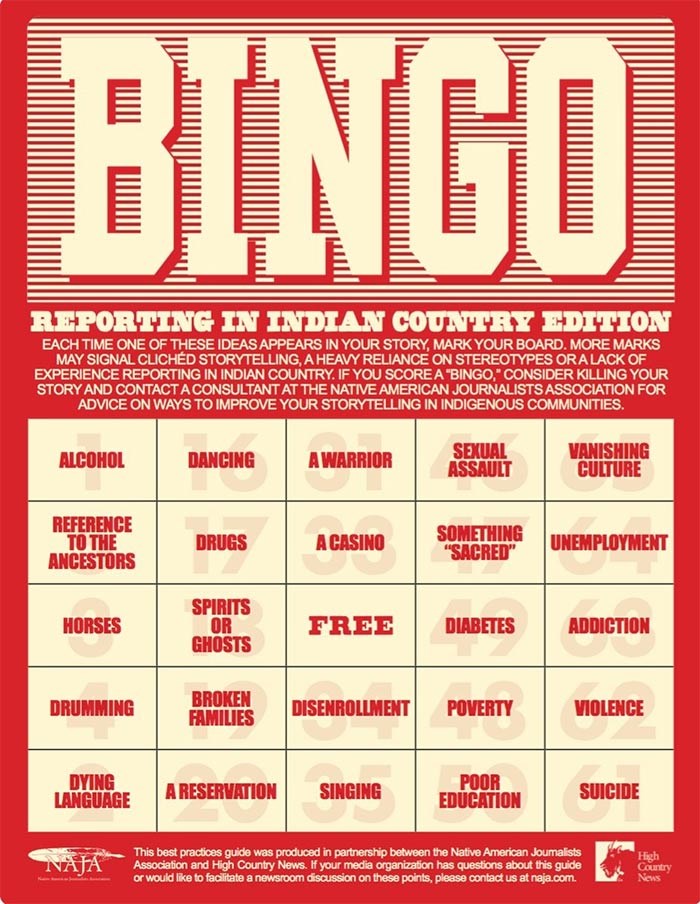

The Native American Journalists Association created this bingo card to help reporters avoid writing cliched and hackneyed stories about Indigenous people. Image courtesy NAJA

Bingo squares include words such as poverty, addiction, drugs, alcohol and suicide. “Vanishing culture” and “dying language” also appear on the board, as does “poor education” and “broken families.” If a reporter has one of these words or phrases in his or her copy, that reporter has to mark that square.

You probably know where this is going – yes, the more squares a reporter fills, the better chance the reporter scores a bingo. And, according to the association, if a reporter scores a bingo, “consider killing your story and contact a consultant at the Native American Journalists Association for advice on ways to improve your storytelling in Indigenous communities.”

Here’s a quote I found in a release from the association. It can be attributed to Tristan Ahtone, the association’s vice president.

“Because news organizations often refuse to commit time, energy or resources to covering Indigenous communities in real or meaningful ways, coverage is often shallow and formulaic. The bingo board is designed to draw attention to stereotypes and cultural bias reporters employ when framing their stories. It’s the responsibility of journalists to combat clichés in order to ensure that information is accurate, fair and thorough.”

I tell you all this because I’m about to score a bingo with the sentences I’m going to write to finish this piece. Such a “win,” though, is unavoidable when discussing the topic of homelessness among Indigenous people in Vancouver and across the region.

Yesterday, the Metro Vancouver agency released a report on the 2017 homeless count that specifically pulled data on Aboriginal peoples. The news is not good. It never has been good in the couple of decades that I’ve followed this topic – Aboriginal peoples account for one-third (34 per cent) of the homeless in the region, despite representing only 2.5 per cent of the population.

It’s the highest proportion ever recorded.

In real numbers, that’s 746 people out of 3,605 counted across the region over one 24-hour period in March.

But there’s likely more, as the report’s authors concluded: “It is important to point out that this count only addressed the most acute form of homelessness – those individuals in shelters and on the street over one 24-hour period – and is therefore very conservative in that it fails to take into consideration those individuals who were simply not counted and those who are at-risk of becoming homeless. One can speculate that the actual number of Aboriginal peoples who are homeless or at risk of being homeless is extreme and much higher than actually reported.”

The reasons for homelessness include poverty, addiction, broken families, poor education, intergenerational trauma related to colonization and the residential school system, unemployment, racism – bingo! – and a lack of housing, where tenants have access to health care and counselling.

Year after year, the story never changes. When the percentage of homeless people counted on the street was 30 per cent in 2013, I got Patrick Stewart’s reaction to the numbers. At the time, he was chairperson of the Aboriginal Homelessness Steering Committee.

He was troubled by the numbers then. That concern hasn’t diminished in 2017.

“Those numbers are people, and we’ve got to be able to house them,” said Stewart, an architect and chairperson of the provincial Aboriginal Homelessness Committee, who continues to implore all three levels of government to build and enable more housing. “We need more safe, affordable housing, we need social housing, we need a federal government that has the political will to put the National Housing Act back on the table.”

I mentioned the bingo card and he agreed the media focuses too much on negative stories about Indigenous people. But, he said, stories that shine the light on homelessness have to be told because the crisis needs attention.

It’s just, he added, that this can’t be the only story told about Aboriginal peoples. Reporters have to look beyond the doom and gloom so often associated to the community. He’s right, and I heard that loud and clear while reporting and writing a series I did last year called “Truth and Transformation.”

I like to think there was some good news in there – the Metis high school valedictorian going to college, the Vancouver police officer from the Namgis First Nation sharing his challenging upbringing to recruits, the Musqueam “knowledge keeper” educating students about the ways of Coast Salish people, the three elders who continue to inspire and lead in their communities.

It’s was refreshing to write these stories.

But today, as the homeless statistics revealed, the news is not good. Tomorrow, Stewart hopes it gets better.

“You can’t focus on all the bad news all the time but, for media, it seems like good news doesn’t sell,” he said as we wrapped up our conversation. “It would be nice to have balance. There’s lots of good stories out there, too.”

That bingo card, it appears, is a work in progress.

Read more from the Vancouver Courier