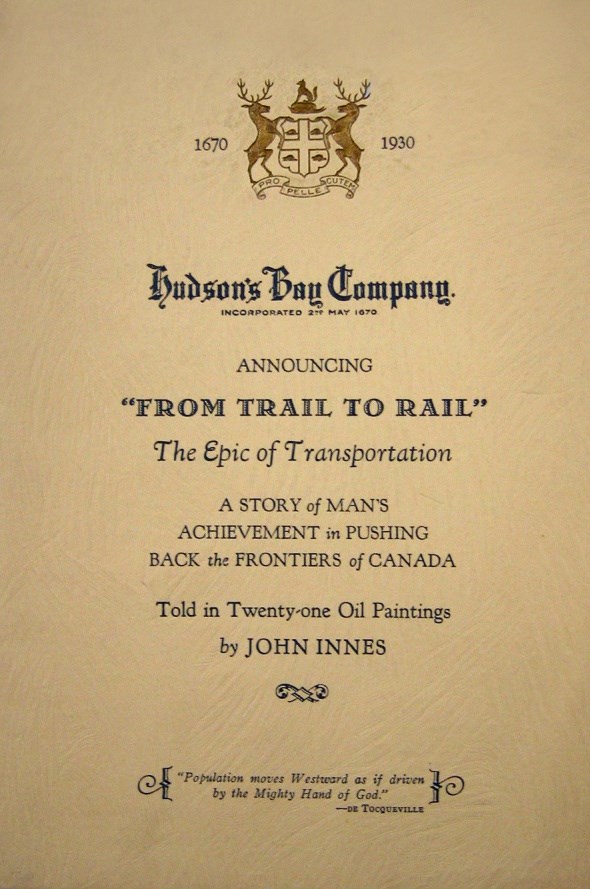

Last week I featured The Epic of Western Canada by John Innes; this week, it's his followup series from 1930 titled From Trail to Rail; The Epic of Transportation. In the words of the brochure, this is the story of man's achievement pushing back the frontiers of Canada in twenty-one oil paintings. Again, it was a collaboration between artist John Innes, art patron Arthur P. Denby, and the Hudson's Bay Company where the works were exhibited. Below is a listing of the 21 paintings:

- A Trail in the Wilderness

- Dog Travois

- Horse Travois

- The Buffalo Hunt

- The Skin Canoe

- A Portage

- The Company Canoe

- Batteau Running a Chute

- Carriers of the North

- The Pack Trail

- Dog Trains

- Red River Carts

- Prairie Schooners

- The Bull Train

- The Buckboard

- The Stage Coach

- The River Steamers

- The Trail of Destiny

- The Challenge

- The Battle of the Rocks

- Triumph

Fortunately, I don't need to track down any lost paintings because I have confirmed all of these paintings became property of the Glenbow Foundation in Calgary. They are not on public display at the moment, but I have acquired an image from the series exclusively for your benefit.

John Innes, “Triumph”, no date, oil on canvas, Collection of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada, 60.71.21

John Innes, “Triumph”, no date, oil on canvas, Collection of Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada, 60.71.21

I've chosen to show the very last painting in the series called Triumph, featuring a steam locomotive headed straight for the artist! Actually, I can attest, this was not John Innes' last painting, but it was the end of his collaboration with Arthur P. Denby. It's unclear exactly what their arrangement amounted to, and even less clear how things fell apart, but John Cowan briefly describes things in his book John Innes: Painter of the Canadian West:

Unfortunately misunderstandings and disagreements arose, for which neither the artist nor patron was wholly to blame, and an alliance that had accomplished much good was ended. The truth is, Innes had driven himself for some years beyond his strength and was worn out. Denby, eager to see these prodigious feats of creative work completed in the artist's years of vigor, had perhaps urged too great effort.

Cowan mentions that Innes had covered the topic of transportation earlier in his career. While working in New York, Innes drew a series of pictures that were purchased by a Philadelphia publisher and released as colour postcards. Apparently it was a huge hit with millions of cards sold.

Alas, commercial success did not come easily after the two epic series. It was now the start of the depression, and over these next few years John Innes saw his health begin to suffer. As the years progressed, he was forced to give up his downtown studio, and later paintings of his favourite subjects took on a much smaller scale. Perhaps this was for the best, as working at large scale did not always work in his favour, never mind the impact of all those paint fumes.

But rather than diminish the work of Innes in his later years, I'd like to sum up this chapter with one last quotation by John Cowan from John Innes: Painter of the Canadian West describing the studio of the artist at work:

The studios John Innes worked in, many in number, were never sumptuous, and were usually littered with an unholy and unsightly collection of junk—pack-saddles, riding boots, stirrups, blankets, books, magazines and miscellaneous debris. As friends left town—miners, prospectors, engineers; a nomadic crew in this western country—the long-suffering artist became custodian of their stuff. But always amid the litter there was reserved a free corner by north windows where sifted, shadowed, smoke-browned light struggled through to the painter's stand where his "chunks of western epic" came to life. It was to such unpretentious, junk-littered, smoke-cured quarters a rare company of democratic spirits—poets, pilots, soldiers, ranchers, miners, prospectors, mounted police, artists, newspapermen—found their way to enjoy his talk and swap yarns. "Jack Innes's studio is an oasis in a business Sahara! I find a visit there as refreshing as a sea-breeze on a sweltering day!" a friend once remarked. This horde of visitors, however, did not further the painter's work, but he loved company and there was seldom any complaint at interruptions.

So is this the end of my coverage of the work of John Innes? Not quite. Next time I'd like to cover the Spencer's murals, made for Canada's Diamond Jubilee / 60th birthday in 1927, these paintings are now relegated to the dustbin of history...