Eight coastal First Nations in British Columbia have entered into an agreement with Ottawa to launch a one-of-a-kind community-based fishing model that would boost access to Indigenous fishing licences and quotas.

In what fisheries minister Bernadette Jordan is calling a “landmark agreement,” the plan will see the federal government transfer funds to help them purchase gear and vessels, and build up local fleets and infrastructure.

“This agreement is a powerful example of what reconciliation can looks like… [it] means restoring the rights of our community members to fish for a living,” said Heiltsuk First Nation Chief Marilyn Slett in a virtual announcement.

By building up the eight First Nations fishing fleets, the plan represents the latest step in a long-fought legal and political movement to transfer autonomy over fishing from the federal government to First Nations.

In one Supreme Court case, a Musqueam man, Ron Sparrow, challenged Fisheries and Oceans Canada's (DFO) fishing restrictions based on “conservation” after he was arrested in the Fraser River. In 1990, six years after the case began, he won, establishing first priority for Indigenous communities to fish for food, social or ceremonial purposes.

But major roadblocks remained, and Indigenous autonomy over their fishing rights was hamstrung by restrictions on how and when to fish, and most importantly, a ban on selling their catch.

That is until June of this year, when the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled in favour of five Vancouver Island First Nations who challenged the DFO's authority over its ability to sell fish and seafood without a commercial licence.

This time around, Coastal First Nations and the ministry responsible for fisheries are working together to ensure those rights for the eight nations: the Haida, Heiltsuk, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Metlakatla, Nuxalk, Wuikinuxv, Gitga’at and Gitxaala nations.

“People who aren’t part of our nation are fishing in our territory,” says president of the council of the Haida Nation Jason Alsop, also known as Gaagwiis.

“It’s not going to be like the good old days. But we believe we can help improve the situation.”

DESPERATE STOCKS

Launching the community-based fishing plan comes at a difficult time for Pacific salmon.

According to research compiled by the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance from publicly available data, salmon populations on the central coast have been in steady decline for several decades.

Sockeye experienced a 90 per cent decline between 1950 and 2020; chum stocks declined by 94 per cent since 1954 and continue to decline at a rate of about 3.5 per cent every year; pink stocks dropped by an average of 89 per cent since the early 1960s; and spawning coho declined by 51 per cent since 2018 as compared to 2000 to 2015 averages.

In addition to impacts from overfishing, a warming climate has led to a spike in ocean acidification and warmer waters, both of which affect salmons’ food supply of krill and small fish species.

Inland, migrating salmon face spiking freshwater temperatures, and recently published research has found up to 85 per cent of historical salmon habitat in the Fraser River — the largest salmon-bearing river in Canada — has either been blocked or has disappeared completely.

Salmon in the Fraser River. From Hope to the river's mouth in Delta, researchers have calculated that over 1,700 kilometres of salmon habitat have been completely lost. By Fernando Lessa

Salmon in the Fraser River. From Hope to the river's mouth in Delta, researchers have calculated that over 1,700 kilometres of salmon habitat have been completely lost. By Fernando LessaAll of those pressures came to a head in June when Fisheries and Oceans Canada announced it would close nearly 60 per cent of the province’s commercial salmon fisheries following a precipitous decline in stocks.

The eight-nation agreement is meant to create a new paradigm to help salmon species bounce back.

It means money generated by Indigenous fisheries will flow into habitat rehabilitation and fish conservation efforts, according to Jordan and First Nation leaders.

“We do believe that there’s ways of adding more value through sustainable fisheries,” says Alsop.

And while the model has yet to be tested in Canadian waters, on the other side of the Pacific, Indigenous communities have shown what’s possible.

LESSONS FROM AN OCEAN AWAY

The eight participating B.C. First Nations and the federal government have been working on the community-based fishing agreement since 2016.

Along the way, Alsop says Indigenous leadership looked to their own community histories for inspiration. But they also looked abroad and how by 2020, the Māori people of New Zealand had used a community-based fishing model to gain 27 per cent of all fisheries quota volume (worth $4 billion) and value (worth $1 billion) in the country.

Bringing in $60 million a year, the Māori-run system re-invests half the revenue back into their companies and distributes the other half to develop and operate the industry. It’s all conducted under the ethic and practice of kaitiakitanga, or environmental guardianship, instead of unfettered resource extraction.

That’s been accompanied by Indigenous-protected areas, which some in Canada have touted as “the next generation of conservation.”

New Zealand's Indigenous fishery model is far from perfect: some criticize its quota system for ignoring wider ecosystem effects; and critics of the Māori management system say it has become a corporate industry dominated by offshore fisheries at the expense of small, family-run operations.

But Chistina Burridge, who heads B.C.’s largest seafood industry group BC Seafood Alliance, says the advantage of the business model is that it still retains the New Zealand government as the entity that provides the science, even though much of the research is paid for by industry and the Māori.

Here in B.C., “we’re not seeing that kind of collaboration,” says Burridge.

HOW TO TRANSITION

A big part of the new plan includes federal funding to First Nations so they can buy quotas and licences from other fishers.

Commercial fishing licences in B.C. have declined to 2,007 from 7,468 in 2003, according to past research and data provided by DFO. Over that time, Indigenous harvesters’ share of the salmon fishery has climbed to 43 per cent, only three per cent higher than in 2003.

The new community-based fishing model is meant to close that gap, boosting the share of Indigenous fishers as a shrinking industry moves to survive.

Burridge says the agreement between the feds and the eight nations could act as a model for a rapidly changing fisheries. She says the Coastal First Nations’ aspiration to be the biggest fishing company in B.C. is “reasonable” and that “they are people we can indeed talk to.”

“We know there will be a transfer to First Nations,” says the industry spokesperson. “That’s OK... So long as it’s on a ‘willing seller and willing buyer’ basis.”

Burridge says the fishers she represents are reeling due to blanket salmon closures announced in June, which have reduced access to nearly 60 per cent of the province’s fishing grounds after a precipitous decline in stocks.

That’s left many non-Indigenous fishers — who tend to be older than their Indigenous counterparts — seriously considering whether it's time to sell off their vessels, gear and quotas, and get out of the business, says Burridge.

“But what will they get for it?” she questions, adding many commercial licences have been effectively devalued over the last few years.

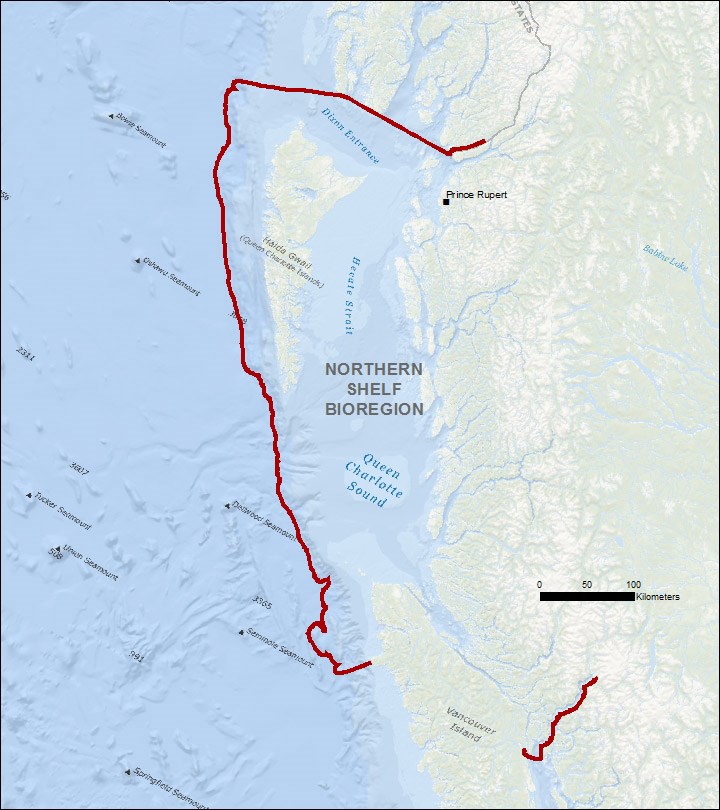

She points to a massive proposed marine protected area, stretching from the top of Vancouver Island north to the B.C.-Alaska border, and set to be negotiated in the fall. If it goes through, Burridge says it would remove commercial fishing access by 40 per cent, putting roughly 400 jobs and $100 million in revenue at risk.

Led by 17 First Nations, as well as the provincial and federal governments, the proposed Northern Shelf Bioregion is one of 13 ecological bioregions identified for protection across Canada. By MPANetwork

Making matters worse, Burridge says there has been little transparency on behalf of the federal government in those negotiations.

“All these things happen behind closed doors. All you have to do is look at the East Coast to see how that can lead to conflict,” she says.

As the plan moves forward, Alsop of the Haida Nation says he agrees all sides will need to be transparent on what is working and what isn’t. But when it comes to the inherent right of non-Indigenous fishers to continue fishing, he’s less equivocal.

“Maybe they’ve extracted enough value over the life of those licences over the years. Maybe it’s time to get rid of those licences,” says Alsop. “It could be a respectful act. A good living was had.”

As details on how the community-based fisheries are worked out, Alsop says his and the other seven nations enter into the agreement with a sense of urgency. As the oceans and the bounty they once held dwindle, he says his nation is ready to do what it takes to help salmon and other species recover.

“We approach this knowing the climate change challenges ahead will be the most importent duty of this generation,” says the president of the council of the Haida Nation.

“Through this agreement and working together, Canada has shown the world that the key to saving the planet is working directly with Indigenous people.”

With files from Matt Simmons, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter/The Narwhal