B.C. researchers have distilled two compounds from a native North American wildflower that could act as a powerful tool to combat drug-resistant tuberculosis.

The discovery of the healing powers of the bloodroot plant, published in the journal Microbiology Spectrum last week, comes at a time tuberculosis remains the second deadliest infectious disease after COVID-19 — killing 1.3 million people in 2022, according to the World Health Organization.

Tuberculosis rates have persisted for decades, if not hundreds of years, said Jim Sun, an assistant professor in the UBC department of microbiology and immunology, and the study’s senior author.

“It’s a huge deal,” he said. “It’s still the leading cause of bacteria-related death.”

Tuberculosis deaths a leading risk in drug resistance

Even with modern medicine, fighting tuberculosis has faced a number of setbacks.

Scientists have never created an effective vaccine for tuberculosis, and Sun said most of the drugs currently used to treat the disease are more than 50 years old. Even drug-susceptible tuberculosis takes four drugs over six months to treat.

“That's a problem. That's hard to keep up,” said the researcher. “When you get into drug-resistance strains, you're talking about one year, two years of treatment.”

In recent decades, poor diagnosis and failure to keep up with antibiotic regimes have helped spur resistance to drugs in certain strains of tuberculosis. It’s all part of a growing drug-resistance crisis that could claim nearly 100 million lives across the world over the next 25 years, according to another recent study.

“TB is a big part of that,” said Sun.

New antibiotics hiding in your flower garden?

One way to fight back against drug resistance is to boost a patient’s immune system. Sun said his lab is involved in figuring out how to turn on human cells that would normally attack tuberculosis but are shut off during an infection.

Another solution to drug resistance is to hunt in the natural world for new antibiotics still effective against the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria.

That’s where the bloodroot plant comes in. For generations, Indigenous peoples have used the plant as a medicine to treat fever, rheumatism, ulcers, ringworm and skin infections. The plant's white and yellow flower is also popular among gardeners.

Some modern commercialization of the plant has led to its use in toothpaste, mouthwash and even as an anti-cancer salve.

Sun’s lab stumbled across the plant while carrying out another set of experiments. At the time, they found it could act as a potential inhibitor for one of the proteins they were interested in. But when they tested it, they also learned it behaved as an antibiotic.

Focusing on the active ingredient sanguinarine, his team increased its potency and reduced its toxicity, in the process creating 35 compounds. Ultimately, the team honed in on two of those derivatives — BDP9 and BPD6 — that showed to be the most effective at fighting aggressive and drug-resistant tuberculosis strains.

Testing showed both compounds were narrow-spectrum antibiotics, meaning they targeted tuberculosis bacteria hiding in immune cells without killing the human body’s beneficial bacteria, known as the microbiota.

“You want to keep those guys alive, for sure,” said Sun.

In a test tube, BDP9 and BPD6 killed drug-resistant tuberculosis strains that take two years to treat in people. And in the lungs of lab mice, BDP9 reduced bacterial presence within eight days.

“We still have to figure out how this exactly happens,” said Sun. “But we do think we are onto something a little different than what’s available.”

The researcher said their work needs to be expanded towards more drug-resistant and more virulent strains of tuberculosis bacteria.

'Definitely worth pursuing'

Bob Hancock, who as the director of UBC’s Centre for Microbial Diseases and Immunity Research did not participate in the study, said the two promising things the bloodroot compounds have going for them are their ability to target dormant bacteria and their apparent compatibility with other antibiotics.

“It’s a very interesting paper, producing something that looks a bit new against an organism that has very few things that work against it,” said Hancock.

And while Hancock cautioned the drugs are still quite toxic and not yet up to standard in mouse trials, he also described the compounds’ properties as “exciting” enough that they could form a whole new range of drugs.

“This is definitely worth pursuing,” he said.

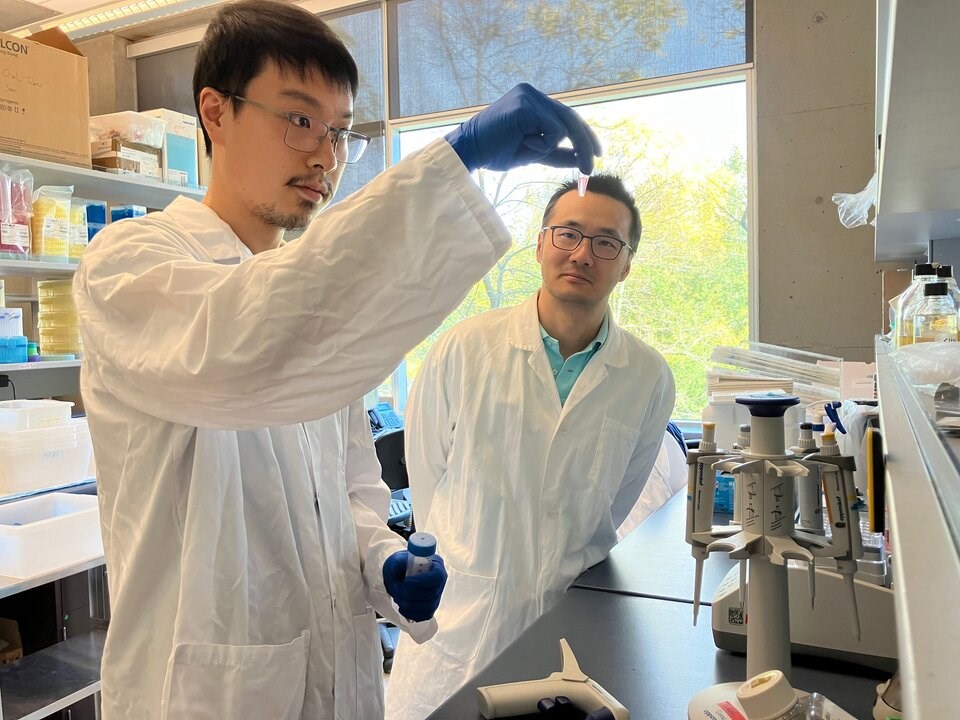

Yichu Liang, the study’s lead author who carried out the drug testing in bacteria and mice as a visiting PhD student at UBC, said that even if future trials are successful, it would likely take years to create a bloodroot-derived antibiotic safe to use in humans.

Still, Liang said, the discovery is a big deal in a world where every new drug could make a difference. If antibiotic resistance doesn’t sound serious, think about what life was like before they existed, he added.

“People could die with just a simple paper cut or any sort of scratch.”