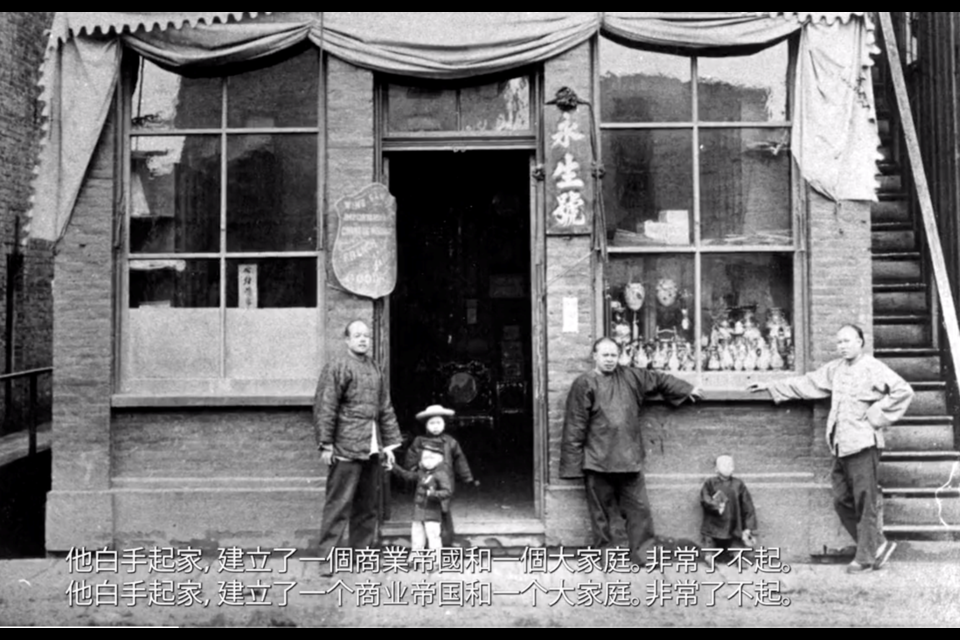

The Chinese Canadian Museum is set to open its doors on July 1 in the historic Wing Sang Building in Vancouver’s Chinatown, after years of planning.

“It is truly groundbreaking and momentous for Canada to have a dedicated museum that honours the history, legacies, and contributions of Chinese Canadians throughout the generations,” said the museum’s board chair Grace Wong.

The museum, founded in March 2020 and brought to life with $48.5 million of government contributions, will provide for exhibitions, educational programming and special events, at 51 East Pender St.

The opening feature exhibition is The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, which focuses on the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Exhibit curator Catherine Clement is said to take museum-goers on a journey that reveals the “haunting stories of loss, despair and fear, as well as powerful examples of courage and perseverance despite incredible odds,” in the face of racism during the exclusion years from 1923 to 1947.

It was on July 1, 1923, when Canada prohibited Chinese immigration and required Chinese people to register with the government or risk fines, detainment, or deportation — the “culmination of anti-Chinese racism and policies, including the head taxes which it replaced,” notes Parks Canada, which will unveil a bronze commemorative plaque at the museum.

The museum also features a recreated 1930s living room in the Wing Sang Building, where Yip Sang and his family lived. And, there’s a recreation of one of Vancouver’s oldest school rooms, from 1914.

A wall mural depicting Chinese-Canadian journeys pieces together past and present, as does the Odysseys and Migration exhibit that “explores the Chinese diaspora from the early waves to present day,” according to the museum’s statement on June 30.

There is also an “interactive immigration map on which visitors can draw and share the origins and immigration journeys of their families.”

The museum’s opening was welcomed by delegates, including Premier David Eby and Mayor Ken Sim, the city’s first mayor of Chinese ethnicity.

“The Chinese Canadian Museum will serve as a testament to the endurance, the triumphs, and the immeasurable contributions of Chinese Canadians to our city and our country,” said Sim.

“I truly hope that people from all walks of life — residents and visitors alike, will take the time to visit this museum and learn of the history of the Chinese Canadian community.”

The museum’s construction was not without some controversy, as a former museum director, Bill Yee, received criticism from Chinese-Canadian groups when he dismissed allegations of a Uyghur genocide in Xinjiang, prompting concerns about how the museum could be politicized by individuals sympathetic or under the influence of the Chinese Communist Party.

Ivy Li, a pro-democracy activist with Canadian Friends for Hong Kong, for example, hopes the museum will recognize and acknowledge the roots of Chinese immigration, including modern-day immigrants from China, and especially Hong Kong, who have chosen to flee the authoritarian communist regime.

Wong said the museum has addressed such concerns with a diverse board of directors and the museum will explore issues from past to present, with the overarching goal of bridging cultures and generations.

Remembering Chinese Exclusion Act should serve education, not ideology: activist

More recently, controversy stirred around the anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act, after Canadian senators Victor Oh and Yuen Pau Woo likened a proposed foreign agents registry (to combat foreign influence and political interference) as a modern form of Chinese exclusion. The senators, often seen in the company of China's consular officials, staged a rally in Ottawa on June 24 to amplify that message.

Bill Chu, founder of Canadians For Reconciliation and someone who spearheaded government redress on the Chinese head tax, said attempts to do so are misplaced and exploitative.

Chu, also a member of the Chinese Canadian Concern Group on the Chinese Communist Party’s Human Rights Violations, said pro-Beijing groups or individuals can amplify anti-Chinese racism for ideological and political reasons; however, “it’s better to be informed by history, not ideology.”

“To the extent we are informed and enlightened by our history, Canada will be a stronger society,” said Chu.

“The political mindset was to get rid of the Chinese,” said Chu of the Exclusion Act. “It was that bad. In that sense we should find no excuse in not remembering it.”