A new assessment of damage caused by extreme weather in 2021 has found heat waves, wildfires and floods cost British Columbia up to $17 billion.

The estimate, released Wednesday in a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) report, found that the combined costs of disaster in 2021 likely ranges between $10.6 and $17.1 billion — far outstripping previous estimates.

That’s equivalent to between roughly three and five per cent of B.C.’s gross domestic product, said Marc Lee, author and a senior economist with CCPA working on climate justice.

“It’s a big number. But I don’t think anyone will be surprised,” Lee said.

Lee says he followed best practices in evaluating economic impacts due to extreme weather, counting both insured and uninsured losses, the cost of damage to governments and hits to individual finances as displaced or stranded workers were prevented from earning a living.

That included roughly 33,000 people evacuated due to wildfire and more than 17,000 evacuated or stranded due to flooding.

During the June 2021 heat dome, workers suffered both financial and physical distress. According to WorkSafeBC, 71 out of 115 worker injury claims were due to heat stress, and the report found high-end labour market losses during the heat wave came to almost $330 million. Construction, food services and drinking places, and manufacturing were estimated to be hit hardest.

Wildfires cost workers up to $562 million, with those in retail trade and accommodation and food services calculated to be the most affected.

And the atmospheric river-driven flooding event is thought to have cost workers — most in transportation and warehousing jobs — almost $1.5 billion, according to the report.

“All of those costs come out of workers pockets,” Lee said.

Insured damages, meanwhile, came nowhere close to what people had to pay out of pocket.

The report found uninsured losses due to wildfire may have climbed as high as $501 million, more than double the $215 million in insured losses incurred in 2021.

At the high end, flooding in November 2021 could have led to almost $5 billion in non-insured damages — over seven times more than the $675 million in insured losses.

“I think that whole thing needs to be rethought,” Lee said. “What’s a more broad-based safety net look like given the disasters we’ll be seeing?”

Governments footed the largest costs — between 40 and 60 per cent of total damage estimates. That includes more than $1.2 billion in public expenditures related to wildfires and $7 billion connected to flooding and landslides.

The report excluded losses outside of B.C., in shipping, or supply chain disruptions in other provinces and territories. Costs associated with loss of life or people’s deteriorating health, such as increases in emergency room visits as extended smoky periods dominated summer skies, were also not included.

With estimates not yet finalized, Lee says even the high-end figure of $17.1 billion could balloon in the coming months and years.

“It’s is still somewhat conservative,” he said.

Call for systematic accounting of climate damage

It’s both challenging and rare to get total economic losses for extreme weather events, says Glenn McGillivray, managing director of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss.

That’s because there are no firmly established boundaries for what should and what shouldn’t be counted as damages.

“I’ve been advocating for this for a long time,” he said. “It helps people plan, for one thing. Secondly, it helps us understand the impacts these events have on people, governments and businesses.”

Perhaps more importantly, McGillivray said if politicians see the costly impacts of extreme weather events made worse by climate change, they may be more willing to act in the future.

“These numbers are really important to get. I applaud this group for trying,” he said.

“Would I bet the family farm on the number? No, I wouldn’t... But they’re going to give you a magnitude.”

Because such estimates are rarely carried out, McGillivray says it’s hard to compare the damage B.C. sustained last year with other provinces who were hit by wildfire, heat and flooding in the past.

“But you can certainly say B.C. got walloped last year. It was one thing after another and to some degree interconnected — the heat wave made forests drier for wildfires, the wildfires disturbed the ground to make landslides more likely,” he said.

“We’re going to see more of this going forward.”

McGillivray says Canada needs to come up with established methodologies to assess the costs of extreme weather, especially now that Canada has released its first National Adaptation Strategy to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

Research from the Canadian Climate Institute has shown every dollar spent on adapting to climate change saves up to $15 in costs down the road. Modelling from the institute suggests climate change will wipe $25 billion off Canada’s gross domestic product within two years. And by mid-century, those annual losses could rise to between $78 and $101 billion.

How to measure insured losses has been well established. McGillivray says the country needs a better understanding of economic losses from extreme weather so it can establish measurable objectives on how to reduce the cost of such events.

But you can’t set objectives if you don’t have a baseline, he said.

“We need to do these studies for every event in this country,” McGillivray said. “And we don’t have that.”

Some have tried.

A professor of engineering at Simon Fraser University, Zafar Adeel spent three years leading a team of researchers across Mexico, the U.S. and Canada who tried to estimate the full cost of natural disasters.

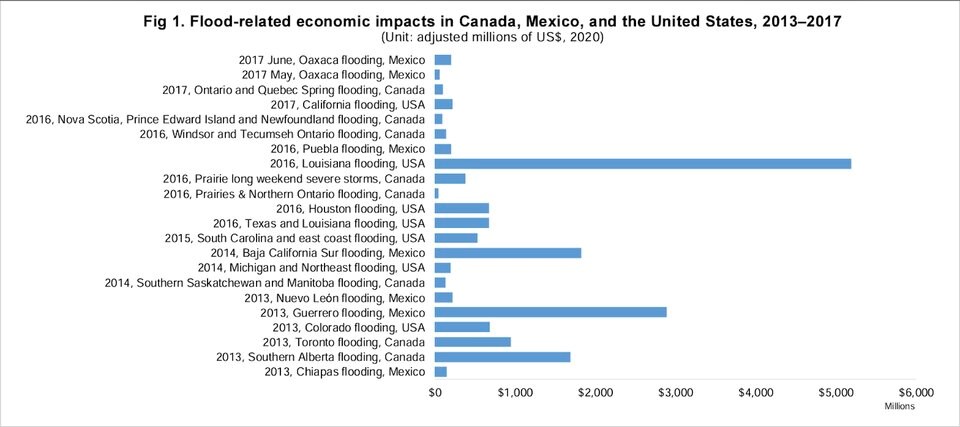

In tallying over 108 cost indicators, the team traced several major floods from 2013 to 2017. But the team came up against a bottleneck.

“One of the main things we found out for U.S. and Canada, there was a huge gap in data availability,” he said.

While Mexico had data on nearly every indicator the group looked at, the U.S. had only 13. Canada had fewer than 10.

Part of the gap comes down to planning. Mexico had created a central government agency and had established a data collection team based on standards recommended by the United Nations. Canadian data, on the other hand, was patchy, incomplete and often measured in different ways by different municipal, provincial and federal agencies.

“Out of the three countries, Canada has the worst quality data to track the damage costs of extreme weather events,” Adeel said.

To paint a full picture of the damage costs due to flooding in Canada, the team turned to CatIQ, a Toronto-based firm that provides analytical and meteorological information on Canadian natural and human-made catastrophes to the insurance industry.

In August 2021, Adeel and his team at the Commission for Environmental Cooperation presented their their fndings to the three governments, along with recommendations that include pooling cost estimates into a shared database so cities and larger governments on all sides of the border have access to same quality information.

“A lot of the data collection happens at the municipal level, but most of the municipal governments don’t have the capacity,” said Adeel.

In five years across all three countries, they estimated major flooding caused US$17 billion in damages, only slightly more than Lee's high-end estimate for the B.C. floods in 2021.

“If those numbers are right... it far exceeds the most disastrous one we saw,” said Adeel.

B.C.’s costs due to extreme weather could still grow, he also warned, especially once you add the cost of emergency response and the indirect effects from damaged energy and utility infrastructure.

It's not always easy to know where to draw the line. Do you count the cost of rebuilding the same $50-million highway to the same standards or do you count the cost of the $100-million highway that can withstand more extreme weather?

Adeel says you have to account for those ranges and it's one reason he says the latest report into B.C.'s damage estimates last year “seem to be reasonable.”

“This report is a really good step in the right direction.”