Despite promises to reduce emissions, eight of the world's largest oil and gas producers are moving ahead on over 200 new fossil fuel projects over the next three years, a new report has found.

The resulting emissions, according to the "Big Oil Reality Check" study published Tuesday, would add 8.6 gigatonnes to the world's carbon budget — equivalent to one-quarter of global emissions in 2020.

Among the projects set to proceed are dozens of so-called "carbon bombs" — mega-projects that in Canada include the Cold Lake oil sands project and the Bay du Nord plan to drill deep into the ocean floor off Newfoundland and Labrador, according to David Tong, author of the report and a researcher with Oil Change International.

Together, Tong estimates forecasted production from those two projects alone could add up to 210 megatonnes of carbon equivalent emissions. In a country like Poland, which has roughly the same population as Canada, that's on par with roughly half of all emissions produced in a year.

"Our analysis shows that all eight of these companies' climate pledges and plans are grossly insufficient," wrote Tong.

A recent investigation by U.K. newspaper The Guardian came to similar conclusions: "Canada and Australia are among the countries with the biggest expansion plans and the highest number of carbon bombs."

At the same time, independent research shared with the British paper indicated Canada, along with the United States and Australia, "also give some of the world's biggest subsidies for fossil fuels per capita."

Tong's analysis also relied on data from the Norwegian energy research and business intelligence firm Rystad Energy.

This time honing in on publicly traded companies, he found that of the world's "supermajor" oil and gas companies, ExxonMobil and Chevron had the least effective climate plans.

His report assessed big oil companies' climate pledges based on 10 criteria. Even meeting all 10 metrics does not mean a company would do its part to limit warming to 1.5 Celsius beyond pre-industrial levels, the threshold beyond which scientists say the Earth will face catastrophic consequences.

Those 10 criteria include stopping exploration for oil and gas, stopping approval of new extraction projects and demonstrating a decline in oil and gas production.

Success in any one of the metrics would likely lead to positive spin-offs for the entire planet.

That's because from 1970 to 2010, fossil fuels and industrial processes accounted for roughly 78 per cent of the total greenhouse gas emissions increase, according to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Over the past decade, the share of emissions from the production and consumption of coal, oil and gas has only increased, rising to roughly 86 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions emitted globally.

In 2021, the International Energy Agency, a longtime policy arm advancing the interests of fossil fuel companies, assessed that no new oil and gas projects could be approved starting in 2022 if the world had a chance to hit net-zero emissions by 2050 and stay below 1.5 C of warming.

But since that landmark report, several new oil and gas "carbon bombs" have received green lights from regulators, including a $12-billion Bay du Nord offshore oil project approved by the Canadian government in April 2022.

Sitting roughly 500 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Equinor ASA project — one of the big eight — is now the subject of a lawsuit after two environmental groups sued to have its approval overturned.

The report also assessed whether each oil and gas company has set explicit goals to phase out oil and gas extraction over the long-term, has ended lobbying and advertisements that obstruct climate solutions and is committing money to help workers transition into other jobs.

"Only three companies expect to drop their production by 2030, and not a single one of those companies anticipates production cuts that are even close to that needed for 1.5 C," wrote Tong in the May 24 report.

"As this analysis shows, none of the oil and gas majors' commitments pass the baseline test to be considered serious climate plans."

Companies deny claims of climate plan failure

Glacier Media reached out to all eight companies analyzed in the report. Only two had returned a request to comment on its findings by publication time.

In a statement, ExxonMobil spokesperson Casey Norton said the company "is committed to meeting the essential needs of modern living, including solutions to address the risks of climate change, and lower emissions."

In the Permian Basin, which extends from West Texas into the U.S. Southwest, Norton said ExxonMobil plans to make its direct operations net-zero by 2030 — something that he said will be applied to its operations worldwide by 2050.

"In doing this, we are working to strike the appropriate balance — investing to help society achieve its ambition for a net-zero future while meeting today's need for reliably supplied, affordable energy," he said.

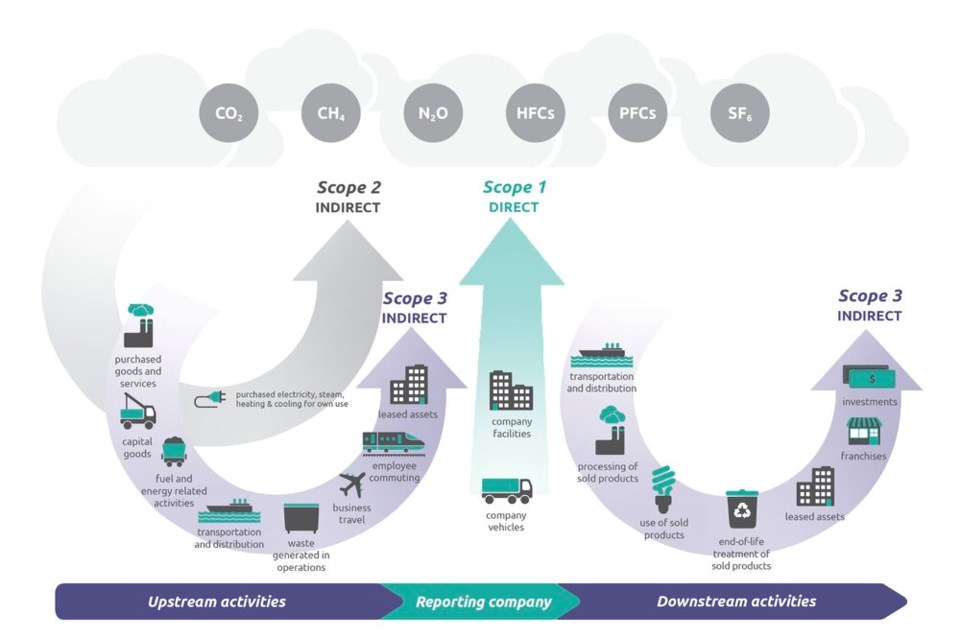

ExxonMobil's net-zero plans do not extend to Scope 3 emissions.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for BP pointed to the company's March 2022 annual net-zero report, where CEO Bernard Looney described BP as "unique among our peers in aiming to be net-zero across operations, production and sales."

Looney added that together, the company's goals are "consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement" to keep temperature rise below 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels.

The spokesperson also said the Oil Change International report failed to consider that BP's emission reduction targets don't include the company's share in Rosneft — the Russian oil and gas giant BP is divesting from over its invasion of Ukraine.

As a result, the report misrepresents BP's reduction targets, said the spokesperson, adding that the company has "stopped corporate-reputation advertising."

Canadian companies' among the worst'

Tong told Glacier Media his latest report undercounts the oil and gas expansion his organization is anticipating in Canada.

"We haven't fully accounted for shale expansion in Canada," he said, adding, "The largest share of expansion in Canada is not coming from the companies we've assessed in these reports."

The report comes six months after Tong conducted a similar analysis looking at the ambition, integrity and transition planning of Canada's eight largest oil and gas producers.

In November 2021, the results were even more "abysmal," found the researcher. In nearly every metric, the oil and gas companies' plans were "grossly insufficient."

Only two companies deviated from failing on every metric.

Shell Canada said it expected its oil production to decline between one and two per cent a year until 2030. But while the company has sold off much of its stake in the Alberta tar sands, it also plans to ramp up investments in natural gas extraction, which could ultimately offset its oil divestment, noted Tong's Canadian analysis.

At a global level, Oil Change International's latest report states that transitioning to natural gas as a so-called 'bridge fuel' would ultimately "take the world far beyond safe climate limits."

Suncor Energy, meanwhile, was the only major Canadian-based company with a plan that even referred to Scope 3 emissions, which include greenhouse gases released from directly burning oil and gas as a fuel and using it as feedstock in the production of plastic or fertilizer.

The company's 2050 net-zero target, however, doesn't count those sources, "even though they account for 80 per cent of the company's emissions," according to the report.

As Tong put it in November, "this research shows that all eight major Canadian companies studied are amongst the worst worldwide, despite all their rhetoric about net zero."

With the data he has gathered, Tong says Canadian oil and gas producers are on track to expand their operations by 30 per cent by 2030. That, he added, will lead to a 25 per cent increase in their emissions.

His message for Canadians: "There is no such thing as net-zero oil and gas production. When companies or governments say there is, they're hiding something."