The pandemic has increased goods and services prices, but for many employees it has also increased wages.

In the pandemic’s first year alone the average hourly wage rate in Canada grew 6.3% – the highest annual growth in the 24 years Statistics Canada has been collecting the data.

A recent report from LifeWorks (formerly Morneau Shepell) says that employers expect to raise salaries an average of 2.7% in 2022.

Some of the industries hit hardest by worker shortages and COVID-19 restrictions, including accommodation and food services, wholesale trade, transportation and construction, are expected to have the largest wage increases.

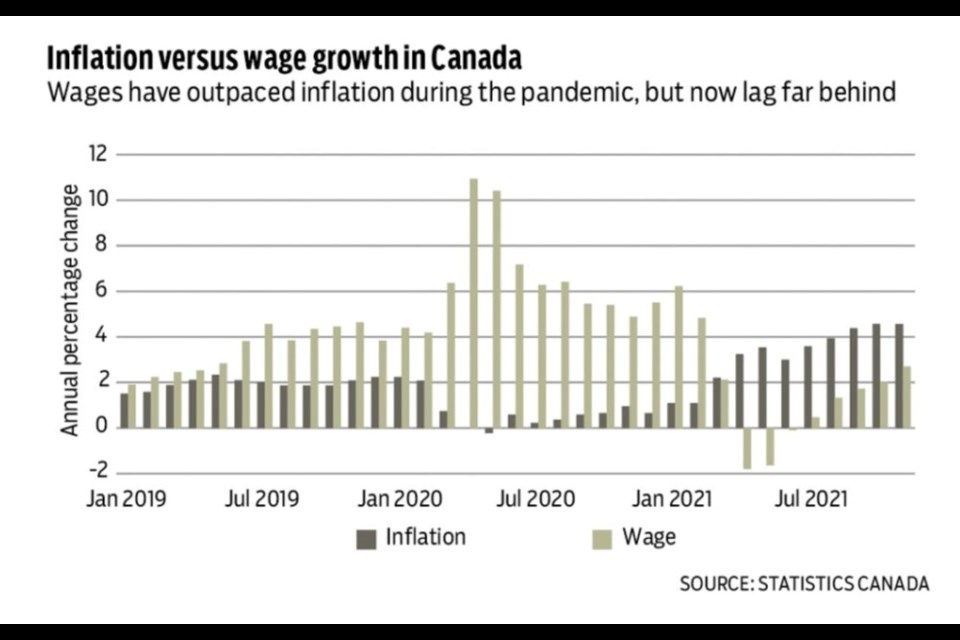

While inflation is high, wage growth has outpaced inflation in 42% of occupations over the past two years, according to Statistics Canada. Only since March 2021 has inflation begun to outpace wage growth. From the start of the pandemic up to that month, wages were growing by as much as 11% annually while Canadians were experiencing deflation, a decrease in the price of goods and services.

However, classifying higher paycheques as wage inflation may be misleading.

“I don’t want to call it wage inflation because that would be a misstatement of what is going on,” said Werner Antweiler, professor of economics at the University of British Columbia.

He said there’s been an employee exodus from many industries, and people are choosing not to return to work. Employees aren’t necessarily leaving for other jobs either; some are choosing to retire early, removing supply from an already tight labour market.

In customer service industries like restaurants and tourism, Antweiler said businesses will need a two-pronged approach to attract new employees: higher wages and improved working conditions.

Currently, there are several economic phenomena happening in tandem. Inflation is increasing the cost of living, and people are using it to bargain for higher wages or employers are voluntarily offering wage increases to account for it. However, a tight labour market characterized by low, pre-pandemic levels of unemployment and even higher job vacancies than there were before 2020 means that wages are rising because of labour market pressures outside of a rising consumer price index.

The effect of rising wages will ripple through macro- and micro-economies. The labour shortage will force some sectors to increase productivity by becoming more capital intensive, relying less on labour. Antweiler said that some businesses will invest in automation and new technology to offset the cost of – or avoid paying – higher wages. For more service-oriented industries where automation isn’t possible, higher wages are only one part of the solution and will need to be paired with improvements to quality of work, work-life balance and working conditions, Antweiler said.

These demands have become so widespread during the pandemic that unions are experiencing a surge in certifications after decades of decline. The Canadian unionization rate increased 1.1 percentage points in 2020, rising above 31% for the first time since 2013.

Higher wages could also cement price increases that have happened across the board, according to Ken Peacock, chief economist at the Business Council of British Columbia. On a macro level, if people use rising consumer prices to bargain for higher wages, that could cause what was once transitory inflation due to COVID and the global shipping crisis to become more permanent.

Antweiler agreed. He said that central bankers are most concerned about a change in expectations and prices that are locked in for long periods of time, like wage contracts.

“These wages they won’t go down again; they will stay up,” he said. “And that would get passed on to higher consumer prices down the road.”