A 1900 photo of Deer Lake included in the Burnaby Village Museum’s new Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide shows a shallow dugout Indigenous canoe of the kind once used by Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ ancestors to navigate local riverways. City of Burnaby Archives

A 1900 photo of Deer Lake included in the Burnaby Village Museum’s new Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide shows a shallow dugout Indigenous canoe of the kind once used by Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ ancestors to navigate local riverways. City of Burnaby Archives

Burnaby Village Museum is taking steps to undo the part it has played in erasing Indigenous history from the place we now call Burnaby.

For several years now, the museum has worked on building relationships with local First Nations, including Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Tsleil-Waututh and Kwantlen, in an effort to bring local Indigenous perspectives and content to the story of Burnaby presented at the museum.

“We have heard from many visitors who remember walking through the village not seeing themselves reflected in the true history of this place we now call Burnaby, so now we are very much focused on creating a museum that feels more inclusive – beginning at the place that feels right, with the Indigenous people of this land,” museum programs coordinator Sanya Pleshakov told city council at a meeting this summer.

Reconciliation work

So far, the partnerships with local First Nations have resulted in the creation of an Indigenous education team at the museum, as well as the addition of a new Indigenous Learning House and Matriarch’s Garden.

This fall, the museum also hosted its first Burnaby Indigenous Week of Learning for Grade 4 and 5 students.

This stone knife, likely used to cut and prepare fish for drying racks, is thousands of years old. It was found near the current site of Burnaby Village Museum. The Deer Lake area was once an important fishing site for hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwxw̱ ú7mesh people. – Burnaby Village Museum

This stone knife, likely used to cut and prepare fish for drying racks, is thousands of years old. It was found near the current site of Burnaby Village Museum. The Deer Lake area was once an important fishing site for hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwxw̱ ú7mesh people. – Burnaby Village Museum

The latest project to come to fruition is the Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide – released this week.

More than three years in the making, it is a 27-page historical overview of local Indigenous history in Burnaby from the time of the ancestors to the present.

A different story

Challenging the idea that Burnaby was an “empty wilderness” developed by European settlers, the guide describes a host of activities hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh-speaking people undertook on the land before contact.

Burnaby was host to many Indigenous villages and resource harvesting sites, according to the guide, including at Deer Lake and the northeast shoreline below Burnaby Mountain.

How this Indigenous presence in Burnaby came to be largely erased – through the reserve system, hunting and fishing restrictions, loss of natural resources because of development, residential schools and the Sixties Scoop – is also outlined in the new history resource.

This stone projectile point was unearthed in 1894 from a midden located where the Burnaby Village Museum is today. – Burnaby Village Museum

This stone projectile point was unearthed in 1894 from a midden located where the Burnaby Village Museum is today. – Burnaby Village Museum

But the work ends by emphasizing local First Nations are still here and still invested in protecting their shared interests in the lands and resources of the municipality.

‘A better way’

The guide was researched and written by Burnaby Village Museum researcher Sharon Fortney, with input from local First Nations.

It was essential for the museum to partner with those communities on the project, according to Pleshakov, because, for too long, Indigenous cultural items, stories and more have just been taken instead of shared with permission.

“Museums in particular have long been implicated in this practice and bear a particular burden of mistrust and broken relationships,” Pleshakov told council.

The history resource guide – suitable for Grade 5 students and up, as well as adult learners – is part of the City of Burnaby’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which has called for municipal governments to educate public servants about the history and continued presence of Indigenous people.

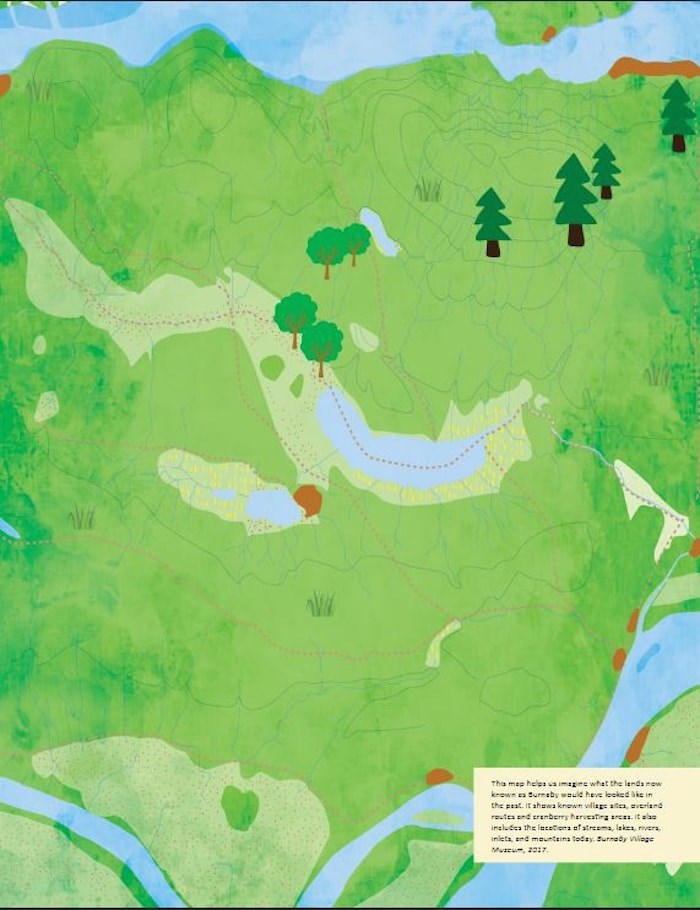

A map in the Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide shows known village sites, overland routes and cranberry harvesting areas, and encourages viewers to imagine what the lands now known as Burnaby would have looked like in the past. – Burnaby Village Museum

A map in the Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide shows known village sites, overland routes and cranberry harvesting areas, and encourages viewers to imagine what the lands now known as Burnaby would have looked like in the past. – Burnaby Village Museum

The commission has also called for the development of curriculum resources that recognize Indigenous people’s historical and contemporary contributions to Canada, so the Burnaby school district has also worked closely with the museum on the history guide, reviewing the document and giving feedback.

“The importance of the guide is that it gives teachers in classrooms local context and a story about the place where our schools are located, so when we talk about our local First Nations, we’re able to talk about spaces and places where our kids live and play. It brings the learning to life in a better way, in a deeper way.”

The Indigenous History in Burnaby Resource Guide is available as a free, downloadable PDF on the Burnaby Village museum website.