In the mid-1940s, as the battles in Europe and Asia wound down, debate in Vancouver was ramping up about a massive project idea: Should the city invest in creating a civic centre?

The idea was a big one with lots of pieces, but essentially the centre would be a series of public buildings all grouped together, potentially including a new central library, a museum, an art gallery, an auditorium, school board offices, a vocational school, federal and provincial offices, and more. Plans for the centre included several city blocks.

The West Georgia centre

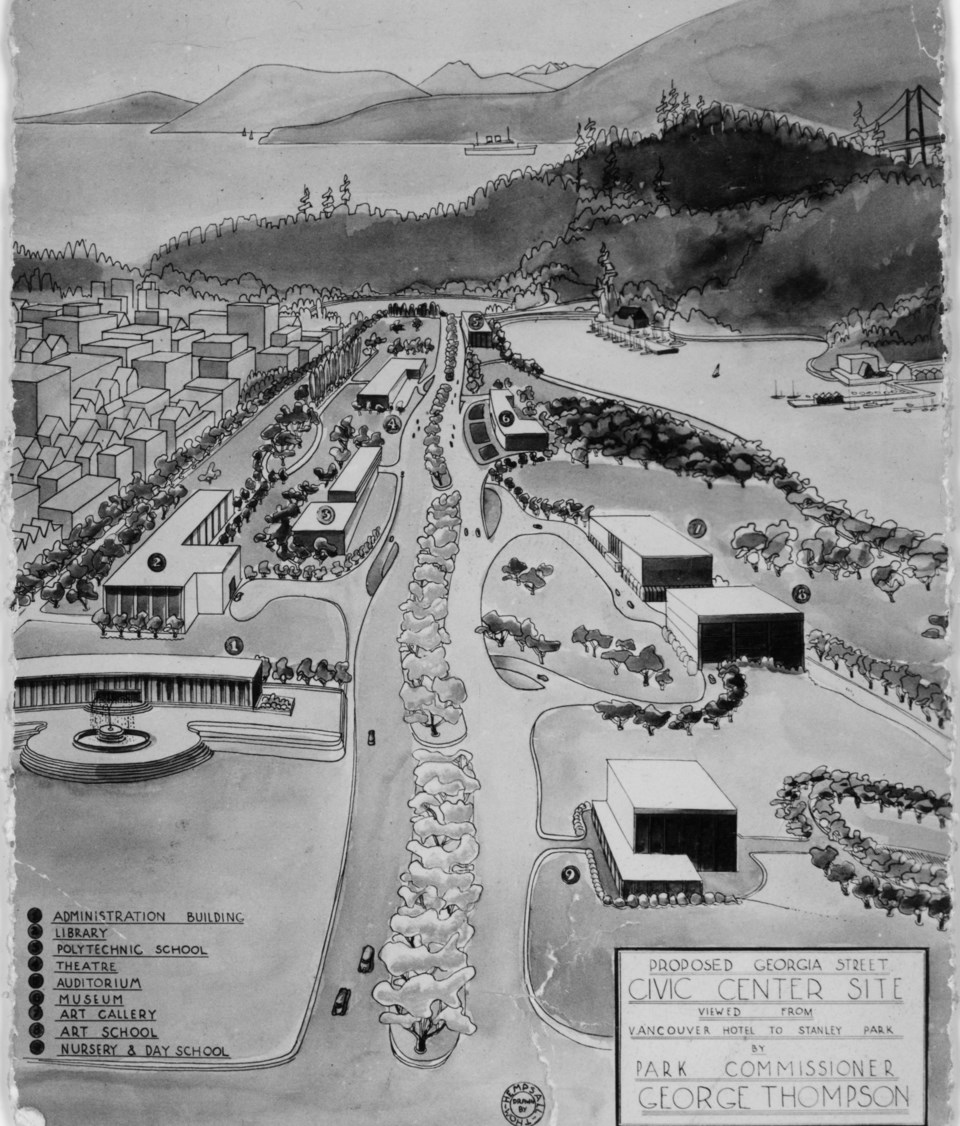

Layouts for two proposed areas still exist. One was for West Georgia as it enters Stanley Park. Proposed by park commissioner and NPA member George Thompson, it was meant to be a grand area and the envy of other cities. In an open letter, he wrote Vancouver was destined to be a great city, but that the locals didn't necessarily appreciate it or put effort into their civic duties.

"Others say in all their travels, they have never seen anything like the beauty there is in Vancouver, but do you really take these people seriously?" he wrote.

"We do not realize our taxes are the biggest bargain we ever get. We wrangle over civic finances, kick about conditions, write editors, and pull down the work of others instead of trying to build and create something that will benefit others in years to come," he added.

The thing he wanted to build, of course, was a grand civic centre, and his ideal location was around West Georgia Street between Burrard and Stanley Park, with Robson Street as the southern boundary. Coal Harbour would become mostly parkland and West Georgia would have a middle boulevard like Cambie Street does.

On the eastern edge, on the southwestern corner of Burrard and West Georgia, would be a large administration building with a large outdoor plaza with a fountain. North of West Georgia would be a school. The art gallery and an art school would be next to the school, with a park leading down to the water.

Further down West Georgia on the north side would be an auditorium (near Cardero Street) and museum (near the entrance to Stanley Park). No other buildings are drawn in the plan north of West Georgia.

South of West Georgia, near the administrative building a library would have been built, with a polytechnical school and theatre next door (across West Georgia from the auditorium).

In all, the plan covered about 180 acres. Most of the land was privately owned; Thompson noted it would be expensive to buy the land.

"I agree that it is costly, and will (run) several millions of dollars," he wrote.

Along with the buildings, fabulous gardens would be part of the massive project Thompson proposed.

"The Georgia Street Site, I believe to be the finest site in Vancouver for our civic centre, and we can make the finest laid-out gardens in the world," wrote Thompson. "We can incorporate Shakespeare gardens, rose gardens, ornamental gardens, and could also include in this project an underground garage near Burrard and Robson streets."

The new civic centred promised to bring renewed growth to Vancouver's West End, according to Thompson. In an article from Dec. 10, 1945, Thompson is paraphrased as describing the area as "nearing obsolescence."

"On the south side of Robson Street, new buildings such as apartment hotels, fine stores, etc. would soon spring up, and this would give us the wonder development of America," he wrote.

That said, he expected it would take "40 to 50 years to complete" which would have seen the finishing touches done in the mid 1990s. But Thompson argued it would be worth it.

"Nothing is too good for the citizens of Vancouver. Let's throw overboard our small town ideas and build Canada's largest and most beautiful city," he wrote.

However, Thompson's grand idea was rejected for a smaller one, but one which would have also radically changed the city's look.

The central city civic centre

The ensuing proposed plan got a lot closer to existing.

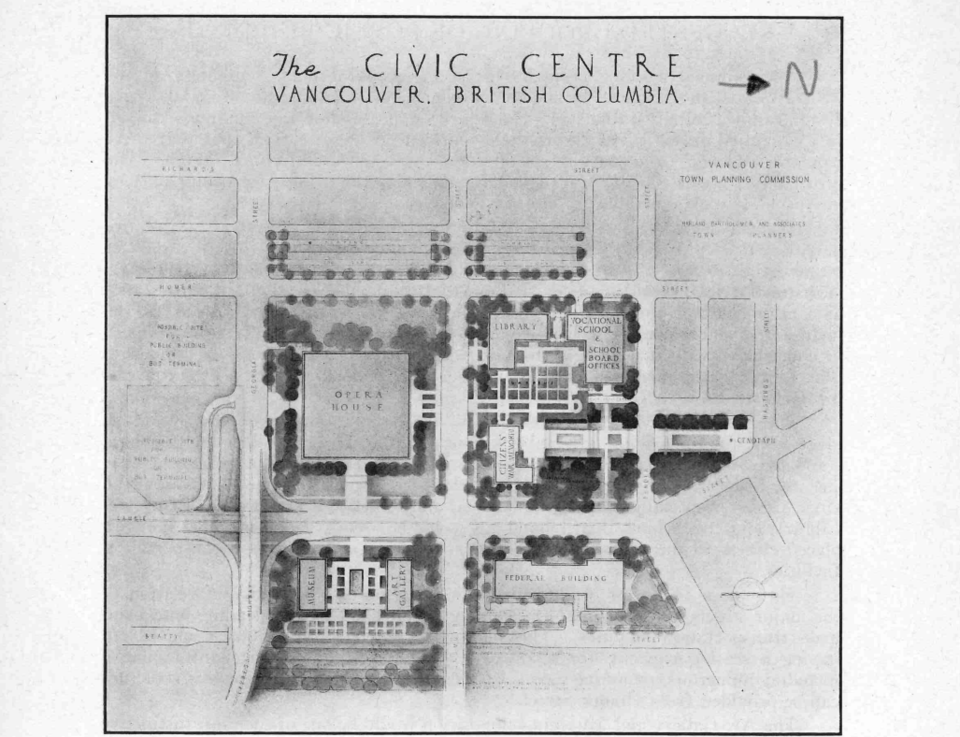

Proposed for a 30-acre site that included the downtown's Central School, the plan covered a six-block area from West Georgia to Victory Square between Beatty Street and Homer Street (and the alleyway just northwest in some designs).

Included in this proposal were many of the same buildings, with different layouts showing a few versions of how it could be plotted out. In all, an auditorium or opera house, museum, art gallery, library, federal building and school facilities were included.

In support of this civic centre, a 3D model was built as an example, setting it up for the public to view. The city's town planning commission published a 22-page booklet to explain the plan as well; it was authored by Harland Bartholomew, the problematic city planner, and his firm.

It appears what gave this plan an edge over Thompson's proposal was the cost. Not only was this civic plan smaller, but it also included land that was already owned by the public, notably Central School, a huge school south of Victory Square; the school and its schoolyard filled a city block - where the Vancouver Community College has space now.

The city's administration estimated $2.5 million was required to buy the rest of the land needed to create the civic centre. That's about $40 million in 2023 dollars.

The issue went to a plebiscite multiple times; in 1946 the central school site was approved and the administration was given the green light by voters to move forward. In the second vote, in March 1947, the public was asked to vote to give permission to the municipality to borrow up to $2.5 million.

In the vote a simple majority wasn't good enough, there needed to be 60 per cent support. When the ballots were counted 14,827 supported getting the loan. 9,995 said no. Supporters made up 59.73 per cent of the ballots cast, falling just 66 votes short.

The city kept pushing for the centre and tried to find other ways to make it work, but it didn't come together. Another plebiscite later in 1947 showed sentiment had soured as the new resolution was soundly defeated.

While the city's central civic centre never came about, some public services have ended up there, or nearby. The city already owned some of the land in the area, and did turn it into a variety of public sites. Notably, Queen Elizabeth Theatre was built in 1959 on one of the blocks.

Perhaps ironically, in the mid-1990s, Vancouver's main library branch was eventually built across the road from the site.