Spanish Banks is one of the most popular places for people to visit in Vancouver in the summer, drawing thousands to hang out on the long sandy beach and swim in the ocean.

If plans had gone through almost 100 years ago that area wouldn't be much fun for a day at the beach.

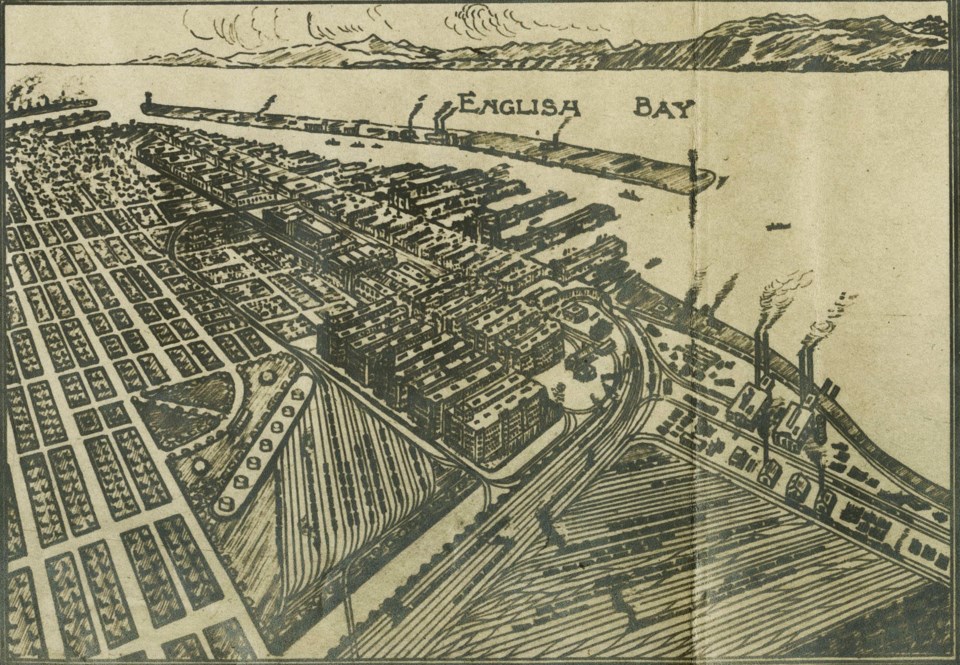

In fact, it would be a massive port, dwarfing both the present-day downtown port and the Robert Banks Superport. More so, it would have been much larger than the two combined, had it been made and it lasted into the 21st century, and ranked among the world's largest ports by size.

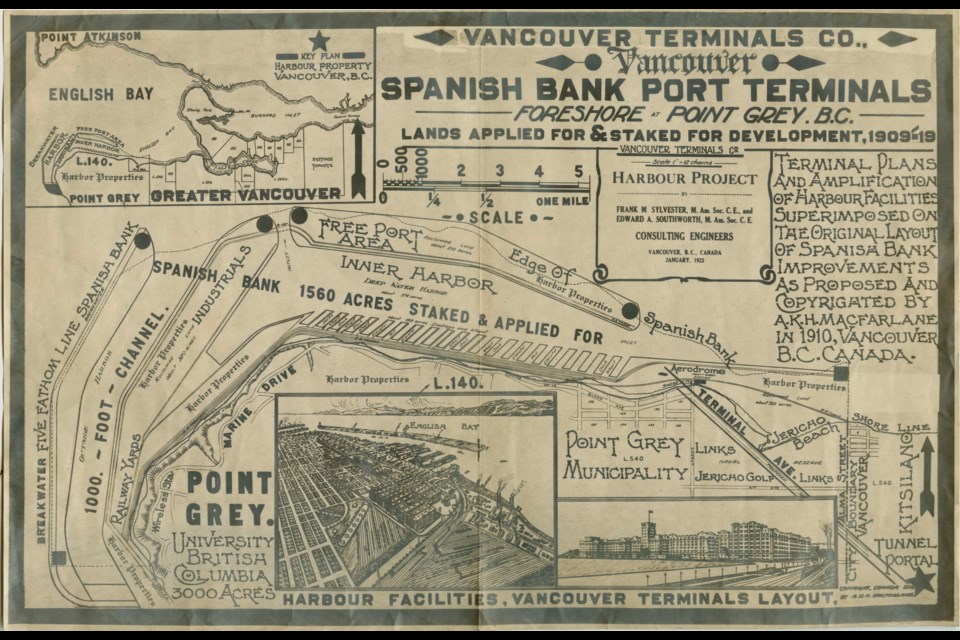

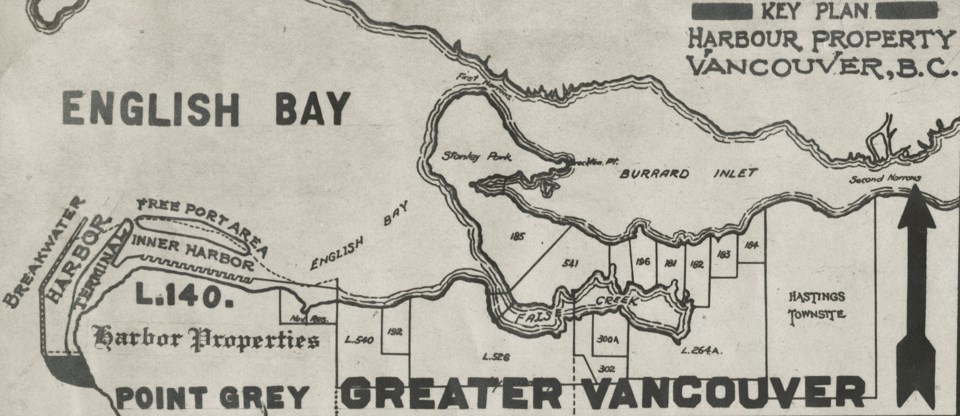

It appears plans were originally floated in 1912, with 20 kilometres of dockage proposed by the Vancouver Terminals Company. The stretch would have run along the beachfront to the tip of Point Grey and a railway would have been built to connect it to the rest of the city.

A big part of the proposal was the reclamation of 700 acres of land; the flat, sandy area covered by tides would have been raised well out into English Bay, though a couple of channels would have remained.

While it would have been a massive mega project, remaking a large piece of land in Vancouver, it was pitched as a way to make shipping easier. Tides and weather would have less of an effect on ships, it would be easily accessible to industry, and administration would be (relatively) cheap and efficient.

It seems developers weren't sure what to do with that area of Vancouver, as an airport was also once proposed for Spanish Banks and a huge development and amusement park was pitched for Jericho Beach.

Drawings show a truly massive port and industrial district

Plans were drawn up for the port in 1923. They show railway yards, industrial lands and docks stretching around the coast from Alma Street to Wreck Beach. In all, 1,560 acres of land and ocean were covered by the mega project.

While the project covered that area, not all of it was fully planned out, so sections were just labelled "Harbour Properties" or "Industrials." However, rail lines were planned out, with a massive railyard covering what is now the UBC shoreline.

The 1923 plan also included 20 huge docks in a 375-acre deep water harbour and breakwaters that would have stretched several kilometres.

The project would have required significant dredging and filling in areas, but the concept wasn't new to the city. The eastern part of False Creek was filled in (the flat area east of Science World used to be marshland) in 1917, and dredging around the Lower Mainland was relatively common.

Plan approved

City council approved the Vancouver Terminals plan and a permit was issued. An initial cost was estimated to be $10 million (around $180 million in 2024).

The vote wasn't unanimous though, and concerns were brought up immediately that the proposed port would ruin the beaches in the area.

However, the council that approved it was the Municipality of Point Grey. Founded in 1908 after it split from the Municipality of South Vancouver, Point Grey included the Southlands, Shaughnessy and the shoreline west of Alma Street.

Plan unapproved

In 1929 the three cities amalgamated into the City of Vancouver that we know now. And with that came a new council and a new plan, literally.

"A Plan for the City of Vancouver" covered several aspects of the future city.

One thing the "Plan" took a look at specifically was the previously approved "Spanish Banks Harbour Project." The pages, dated from 1928, estimate the cost to be at least $75 million (in the neighbourhood of $1.3 billion now). This was less than a year before the Great Depression.

Along with the much higher cost, the scale of the project was questioned in the report, as the city and province didn't need a port that size.

Another issue raised some may find funny now: There was lots of shoreline available.

According to the report, plenty of water frontage along the Burrard Inlet was undeveloped and there were lots of other areas in the region that could be turned into a port a lot more easily than by dredging and filling in Spanish Banks.

"The Spanish Banks Harbour Development project is apparently not founded upon a sound economic basis, and, as any attempt to carry it out would destroy about the last remaining beach accessible to the people, besides depreciating in value one of the finest residential and university sites on the coast, it is unhesitatingly recommended that this project be not encouraged as opposed to public interest," wrote W. M. D. Hudson in the plan.

That, it seems, effectively killed the idea.