Former Vancouver Courier contributor Aaron Chapman’s book, Vancouver After Dark: The Wild History of a City’s Nightlife, published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2019, delivers on its title’s promise. Over the course of 246 colourful pages, Chapman dishes on this city’s most famous and infamous entertainment venues over the years. In this exclusive excerpt, he looks back at The Marco Polo, the legendary Chinatown hotspot that hosted the likes of Richard Pryor, Redd Foxx and a scintillating Nina Simone before eventually closing in 1982.

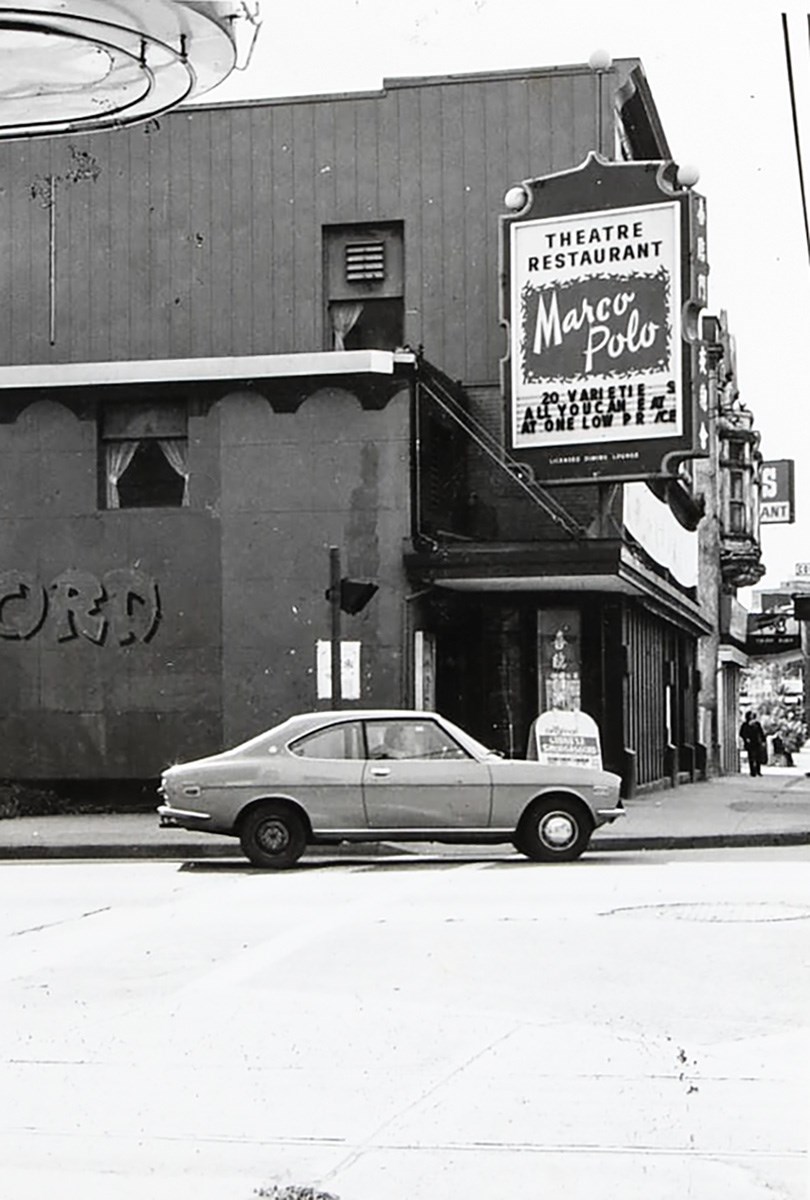

On the night of Nov. 18, 1964, the Marco Polo nightclub at 90 East Pender St. hosted its gala grand opening. Harvey Lowe, looking sharp in a suit and tie, took to the stage to emcee. Once the owner of the Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret, Lowe was more widely known to the public as both a radio host and a world champion of the yo-yo during his childhood in the early 1930s. Tonight, as he emceed, Lowe whirled his yo-yos back and forth, up high and down low. One expected to see him pick off the drinking glasses along the tables in the front row. These were well-worn tricks he had once displayed at talent shows as a kid and now continued to perform during his nightclub appearances. The shtick might have worn a bit thin by the mid-1960s, but on this night, Lowe earned a healthy round of applause from the full house.

Waiting in the wings was Ayako Hosokawa, a singer who’d come direct from Japan. Vocalists were backed by the house band, the Marco Polo Orchestra, featuring local bandleader Carse Sneddon. The Marco Polo promoted this night’s entertainment as “Canada’s only Oriental Revue,” showcasing a floor show that featured “a glamorous line of Chinese Beauties” called the China Dolls.[1]

If all that wasn’t enough to satisfy, a 300-pound barbecued whole pig was the centrepiece of the restaurant’s massive Chinese smorgasbord. Chinatown had never seen anything quite like it.

Among all the clubs that have existed in Chinatown over the years — including its many nameless illegal gambling and opium dens from the very early days — the Marco Polo is perhaps the most legendary nightspot in the neighbourhood’s history. The club became one of the city’s significant live entertainment venues of the 1960s and ’70s. Although local popular opinion might deem the Cave, the Palomar and Isy’s to be the city’s pre-eminent supper clubs, the Marco Polo, a late arrival on the scene, quickly acquired an audience and atmosphere all its own.

Between 1904 and 1917, 90 East Pender St. housed the terminal station for the Great Northern Railway. When the train line was decommissioned, the track was removed, and by the 1950s, the station’s walls and foundation were repurposed to build the Forbidden City, a Chinese restaurant owned by Jimmy Lee, who also owned the May-Ling Club at 442 Main St.

In 1959, Lee consulted a Chinatown fortune teller, who advised him it would be a bad year for business. Although he hadn’t experienced any problems with the business, this ominous warning made him fearful, and he sold the Forbidden City. By 1964, the space was given new life as the Marco Polo theatre restaurant by owners Victor Louie and his brothers.

The brothers were from one of the most successful Chinese Canadian families in the city. Their grandfather H.Y. Louie had emigrated from China, around the time the Marco Polo was still a railway station, and become a produce wholesaler. Their uncle Tong Louie was owner of the London Drugs and IGA supermarket chains. Another uncle, Tim Louie, had become a judge and police commissioner.

However, the Marco Polo didn’t cater exclusively to Chinese Canadians. The name alone seemed to convey that non-Asian Canadian diners were more than welcome to come and explore Chinese cuisine. With its 14-page menu, the club offered a seemingly endless variety of dishes — at a time when dining choices in Vancouver were nowhere near as varied as they are today.

“You could usually rely on Chinatown being a good option for restaurants,” recalls legendary local radio DJ Red Robinson, who had ample opportunity to sample restaurants while broadcasting from practically everywhere across the Lower Mainland over the years. Back then, Robinson recalls, “there was nothing. The White Lunch? It was just diner food! Just boiled stuff, and maybe some tapioca pudding to finish, with the little eyes staring back at you! Trader Vic’s was a big deal when it opened, because before that, the benchmark places in Vancouver were the Devonshire Hotel restaurant or the Georgia. So Chinatown was always an option and welcome relief, with places like the Mandarin Gardens, the Ho Ho, and the On On. What was different was the Marco Polo was a cross between those places with Chinese food, but it also had the shows.”

The Cave and Isy’s featured more of the A-list performers in town, but the Marco Polo hosted many varied and notable acts. Hip American comedians Richard Pryor and Redd Foxx performed at the Marco Polo, as did musical comedy nightclub mainstays like Pete Barbutti. The club also hosted groups such as the 5th Dimension and Sly and the Family Stone, as well as retro acts like the Platters and Bill Haley & His Comets.

But it was a March 1968 engagement at the club by Nina Simone that was perhaps the most notable of all the shows at the Marco Polo. It even caught the attention of Vancouver Sun columnist Denny Boyd. Boyd wasn’t a regular music reviewer and tended to enjoy the more mainstream style of entertainers, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, and he wasn’t normally inclined to offer effusive praise about any musical performer — but even he was bowled over.

“In this day of kiss-blowing entertainers, who beg their audiences for love, Nina is an iconoclast,” Boyd wrote. “A glorious singer and sensitive pianist, she thrilled a Marco Polo audience into respectful silence last night. She doesn’t smile because she is totally absorbed in her music, none of which is frivolous. When she finishes a song there simply isn’t another word to be said about the subject.”[2]

During Simone’s set at the Marco Polo, an audience member unexpectedly spoke up and questioned her right to sing songs that criticized racial injustice while she was in Canada, where, the patron apparently insisted, there wasn’t the same kind of discrimination. Simone’s reaction was immediate: “Literally shaking with emotion,” Boyd wrote, “she reduced him to ashes with a fiery outburst in which she attempted to bring him up to date. Go see her, and hear her message.”

If there was one newspaper columnist who was completely at home at the Marco Polo it was Vancouver Sun entertainment editor Alex MacGillivray. If the Cave was Jack Wasserman’s beat, then the Marco Polo was surely MacGillivray’s. He wrote regular dispatches about the wide variety of entertainment on display at the club. But his writing did not always please everyone.

“In one review in the newspaper, he gave the China Dolls a bad review,” recalls his daughter, Caroline MacGillivray. “The next time he came into the Marco Polo, Pamela Hong from the China Dolls walked up and needled him about it, and really told him off.” MacGillivray must have made amends somehow — they eventually married and Pamela gave birth to Caroline. And for Caroline, it was always a treat for her as a child to visit the place where her parents first met. “It was my favourite restaurant. I loved the smorgasbord and the almond cookies,” she recalls.

By the mid-1970s, the Marco Polo greatly reduced the number of shows they offered. As the Cave also experienced around that time, the era of the supper club acts was coming to an end, and with it, so did the clubs themselves.

The Marco Polo continued to function as a popular restaurant for a few more years but moved to North Vancouver in spring 1982. When the Marco Polo closed in Chinatown, it seemed to mark the end of a unique time in the history of Vancouver’s nightlife, especially for those who had been moved by the performances they’d seen in the club — people like Denny Boyd, who would never forgot that Nina Simone show, and believed that the Marco Polo closing, after the closure of the Cave a year before, marked the end of an era.

Boyd delivered a passionate eulogy for the Marco Polo in the Vancouver Sun, lamenting how quickly the city had changed, and expressing cautious optimism about where he thought the city was heading. “It wasn’t too long ago that this was nightclub city,” he wrote. “You could go downtown with a $20 bill in your pocket and see a class act. Uptown we got the major acts at the Cave and Isy’s. Downtown, we got the new acts, plus gold coin beef and steamed broccoli, at the Marco Polo.”[3]

“Talent broke at the Marco,” he continued. “The bad ones are forgotten, but some went onto stardom. They were new, they were hungry, and they worked hard at the Marco Polo, and they respected your entertainment dollar. It was a fun place, and there aren’t any fun places left. Maybe I’m missing something. Maybe Vancouver doesn’t want to chuckle any more. Maybe the climate’s too wet and the economy’s too dry for laughing. All I know is I never saw a bank tower I liked.”

In 1983, the Marco Polo building was demolished. A new structure was erected on the site that currently houses one of the campuses of Vancouver Film School.

—Aaron Chapman

1. John Mackie, “This Day in History: 1964,” Vancouver Sun, Nov. 16, 2012, 2.

2. Denny Boyd’s column, Vancouver Sun, March 8 1968, 23.

3. Denny Boyd, “The Curtain Drops on Marco Polo,” Vancouver Sun, January 27, 1982, 3