A Vancouver time travelogue brought to you by Past Tense.

The murder scene. Chinese Freemasons Building, 5 West Pender Street

The murder scene. Chinese Freemasons Building, 5 West Pender Street

Historical walking tour season is upon us, folks. There are several excellent ones to choose from these days. I recently went on the Vancouver Police Museum’s popular Sins of the City tour and thought I’d share one of the stories featured on the walk.

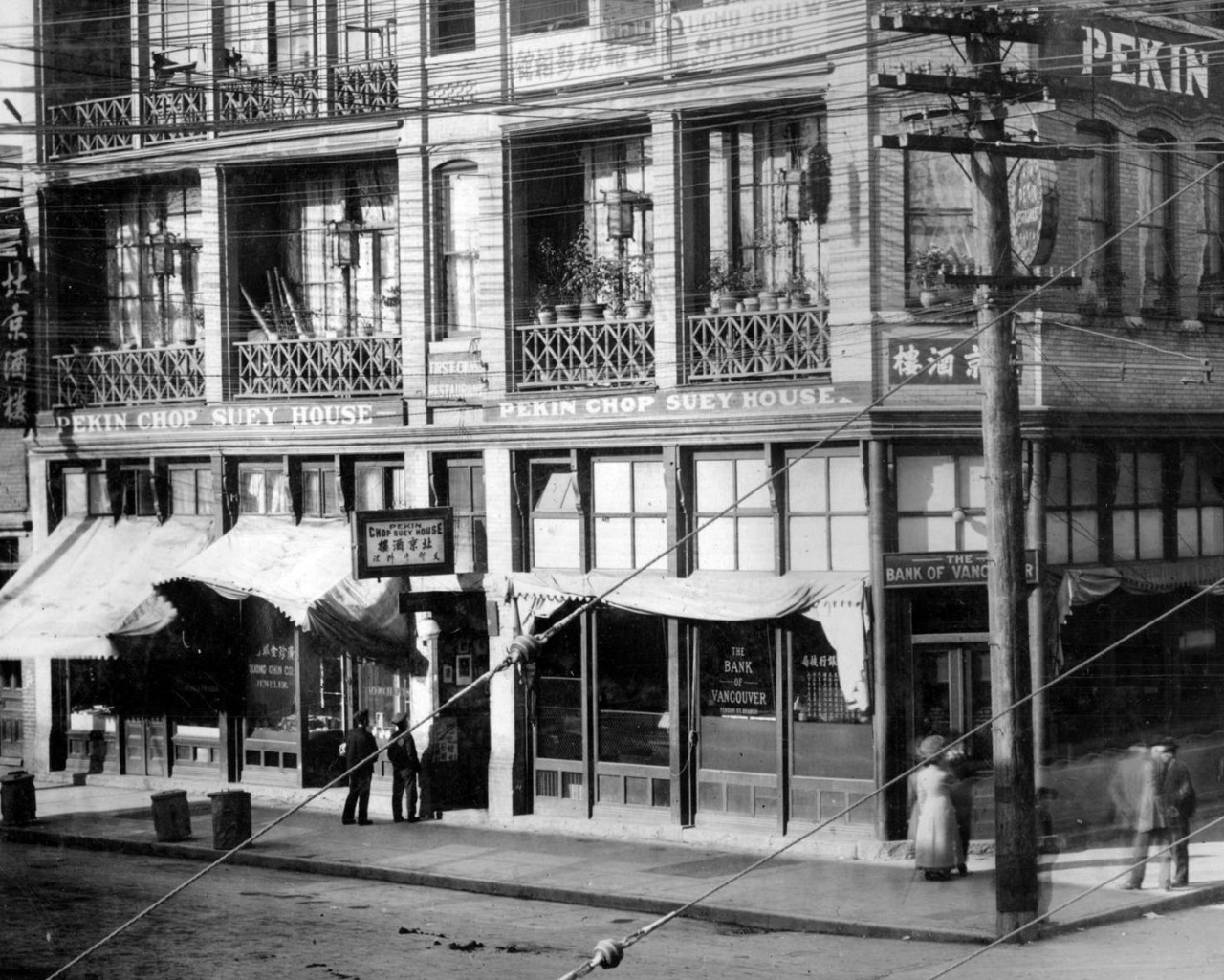

Constable John Mackie was at Hastings and Carrall Street when he heard gunshots one September evening in 1924. He ran a block south, where a crowd was forming at the entrance to Pekin Chop Suey on West Pender Street in Chinatown. Just inside the entrance, Mackie found Lew Hung Chang, known in English as David or Davie Lew, lying on the ground, alive, but riddled with bullets. Lew wouldn’t survive the trip to the hospital. Witnesses reported seeing a man flee around the corner, and sure enough detectives located a .38 revolver with five spent shells in Market Alley behind the BCER terminal.

David Lew was one of the most prominent and influential figures in Chinatowns in Vancouver and around BC. Born in Canton but educated in Vancouver’s public schools and UBC’s law school, Lew was invaluable to Chinese people dealing with business and legal matters even though he could only informally practice law as a “confidential agent” because of his race. Chinese men like Lew who were intimately familiar with both Chinese and white societies made them indispensable intermediaries between the two worlds and power brokers within the Chinese community.

At the time of his death, Davie Lew was working on a report of the abduction of Wong Foon Sing, the wrongly accused houseboy who was abducted by vigilantes in KKK hoods during the infamous Janet Smith murder case. Lew’s other credentials include serving as China’s assistant consul for Western Canada and as a key figure in an investigation by Mackenzie King into Asian immigration to Canada.

Lew’s murderer was never caught, but in the weeks following his death, newspapers rolled out numerous theories. The general consensus was that the assassin was brought in from Victoria or possibly San Francisco. The killing bore the marks of a well-planned execution, including the detonation of fireworks in the vicinity in the days leading up to the hit so that passersby wouldn’t be alarmed by the sound of gunfire.

Many people thought Lew was targeted by one of the Chinese “tongs,” clan associations or secret societies that sometimes doubled as crime syndicates. One theory was that Lew earned the enmity of a powerful tong for working to bring justice for a man who had been assaulted with a hammer in a dispute between rival tongs. Another report suggested Lew was on the verge of exposing a sex slave/human trafficking ring operating along the coast and that’s why he was killed. Still another rumour was that he was killed for his involvement in a blind pig investigation that implicated the mistress of a powerful tong leader.

None of the theories explaining Lew’s assassination were ever substantiated and police faced a wall of silence from Chinatown denizens fearful of repercussions. An elderly Chinese man from Victoria was finally charged, but was easily acquitted because, as his defense lawyer put it, “you would not hang a dog” on the evidence that was presented, “let alone a human being.”

Funeral procession for Davie Lew

Funeral procession for Davie Lew

With an eye to the upcoming civic election, Mayor Owen—emboldened by Lew’s murder and the Janet Smith case—declared “war on the Chinatown underworld” and “gave the police a free hand to go the limit,” even if it meant raiding the same establishments several times a day. The Chinatown crackdown continued until Owen lost to LD Taylor in the mayoral contest. Although he had agitated against Vancouver’s Asian population as owner of the Daily World newspaper, Taylor believed the petty gambling operations being targeted in Chinatown should be very low on the list of police priorities.

Sources: Photo of David Lew: Vancouver Sun, 25 September 1924; Pekin Chop Suey House, 1911 (cropped): City of Vancouver Archives #M-14-62; Funeral procession for David Lew: Photo by Stuart Thomson, Vancouver Public Library #17717