A Vancouver time travelogue brought to you by Past Tense.

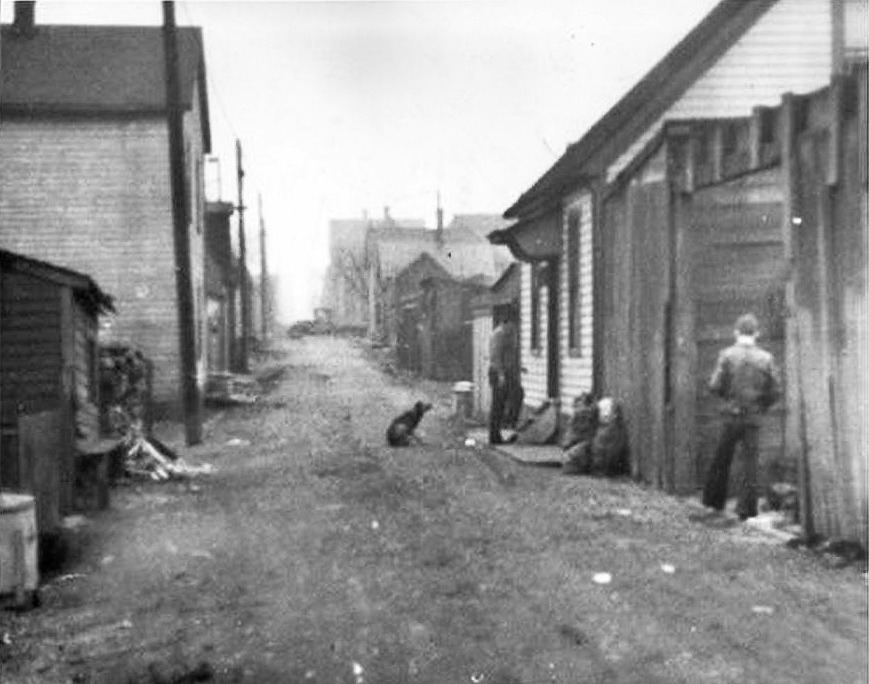

Hogan’s Alley, Wednesday 31 March 1937

Hogan’s Alley, Wednesday 31 March 1937

2014 will see three Vancouver history stamps from Canada Post. The 100th anniversary of the Komagata Maru incident will be commemorated in May and Claude Dettloff’s iconic WWII photo, “Wait for me, daddy,” will be issued in November. A stamp commemorating Hogan’s Alley was issued a few weeks ago to mark Black History Month.

Hogan’s Alley is being recognized as a focal point for Vancouver’s black community before it was demolished as part of an urban renewal campaign. During most of its existence, however, it had a reputation as a hub of vice and crime, not unlike Main and Hastings does today. From outside appearances it didn’t look much different from any other East Vancouver laneway, but some of the rickety shacks lining the alley housed bootleggers, gambling dens, and juke joints. The squalid conditions in the East End generally, and Hogan’s Alley specifically, were often assumed to generate crime and other social ills.

Hogan’s Alley was depicted in “Chang Suey,” a Ubyssey satire of the pulp fiction detective stories that were popular in the 1930s. The stories were set in Vancouver and, as this excerpt illustrates, give an indication of how the alley was perceived in the real world:

He placed his finger on part of a street marked Hogan’s Alley. I looked and saw that the marks representing crimes clustered about the spot, spreading out more and more thinly in the districts further away … “James, my hat and coat,” he said absent-mindedly, “We must be going. I am going to trap that Chinese villain in his lair in Hogan’s Alley. It is there that he has his crime machine. Statistics prove it and even Bulldog Drummond would be convinced.”

Crime statistics were in fact notoriously unreliable when they were compiled at all in the 1930s, and even the police thought it was ridiculous to characterize this small alley as a major crime centre. Some accounts claim that Hogan’s Alley’s bad reputation was due to the behaviour of visitors from other parts of town “slumming it” in the East End.

Only after the 1979 publication of the oral history collection, Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End, years after the heart of Hogan’s Alley was bulldozed to make way for the Georgia Viaduct, was it acknowledged as a bona fide community. In the collection, musician Austin Philips describes a place that was lively, but more fun than menacing:

There was nothing but parties in Hogan’s Alley. Night time, anytime, and Sundays all day. You could go by at 6 or 7 o’clock in the morning and you could hear the juke boxes going, you hear somebody hammering on the piano, playing the guitar, or hear somebody fighting.

For more on Hogan’s Alley and the black community in the area, see Black Strathcona.

Source: Vancouver Sun