A Vancouver time travelogue brought to you by Past Tense.

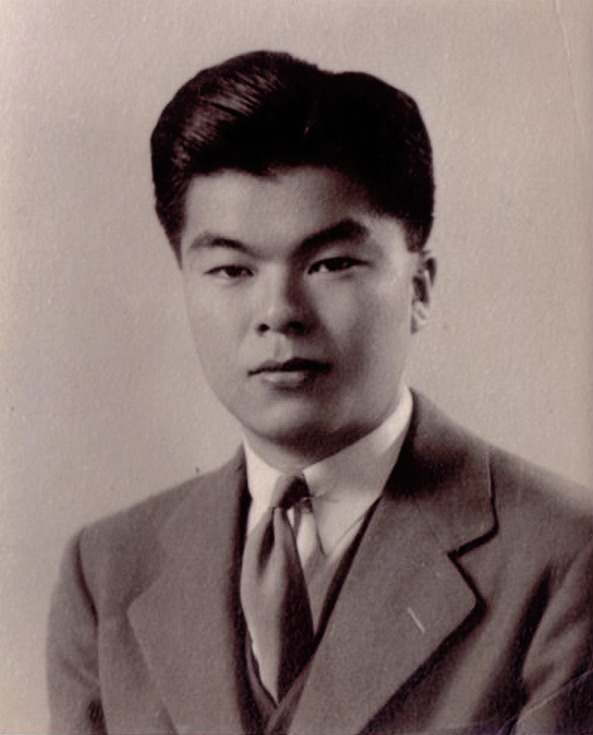

Shuichi Kusaka

Shuichi Kusaka

Shuichi Kusaka was five years old when his family moved to Vancouver’s East End from Osaka, Japan in 1920. The family lived at 368 East Cordova Street and Shuichi attended Strathcona Elementary School, Van Tech, and Britannia High School before enrolling in UBC in 1933. Kusaka was a brilliant science student, earning numerous scholarships and graduating at the top of his class, for which he became the first Nikkei (Japanese-Canadian) awarded the Governor-General’s Academic Medal.

UBC wasn’t exactly on the forefront of theoretical physics in the 1930s. A classmate of Kusaka’s recalled the experience years later:

We did practically nothing in the way of modern physics at British Columbia, because no one knew any. We had a course in what was happening in modern physics—some of the experimental work—but nothing in the way of theory. No one there knew any nuclear physics. But a bunch of us got together and we gave ourselves a course in quantum mechanics … So we gave ourselves a course in elementary quantum mechanics, which at least taught us something about the world, but not much.

The classmate was Robert F. Christy, a Vancouver boy best remembered for his work on the Manhattan Project. After UBC, Kusaka earned his Masters at MIT, and then followed Christy and another UBC grad, George Volkoff, to study at Berkeley under J Robert Oppenheimer. UBC may not have been at the forefront of modern physics at the time, but under Oppenheimer, these alumni found themselves at the cutting edge of the theoretical physics that gave rise to the nuclear age.

Kusaka was offered a job in Osaka by the man who would become the first Japanese to win the Nobel Prize, but by the time he finished his PhD in 1942, the US was at war with Japan. Oppenheimer and other science luminaries defended Kusaka against anti-Japanese racism during the war. If not for his race, Kusaka might have been recruited to the Manhattan Project, but instead found a job at Smith College in Northampton, despite vociferous protests from unions and townspeople over the hiring of a Japanese person. College officials stood by their hire based on the strength of his work, and pointed out that he had been vetted by the FBI, the State Department, and the Immigration Department. Despite racist threats and blustering, Kusaka’s time at Smith was mostly uneventful, save for a tomato throwing incident.

Kusaka joined the US army in 1945, but was released the next year because Princeton University was desperate for professors qualified to teach advanced nuclear physics. At Princeton, Kusaka worked with Wolfgang Pauli (1945 Nobel Prize winner) and Albert Einstein (whose biography Kusaka edited). By this point, the thirty year-old Kusaka had already made significant contributions to theoretical physics, had been awarded two of the most prestigious post-doctoral fellowships in the US, and had been recognized by the shiniest stars in physics. Sadly, his budding career was cut short when he drowned while swimming in New Jersey in August, 1947.

Source: Okayama University of Science