A Vancouver time travelogue brought to you by Past Tense.

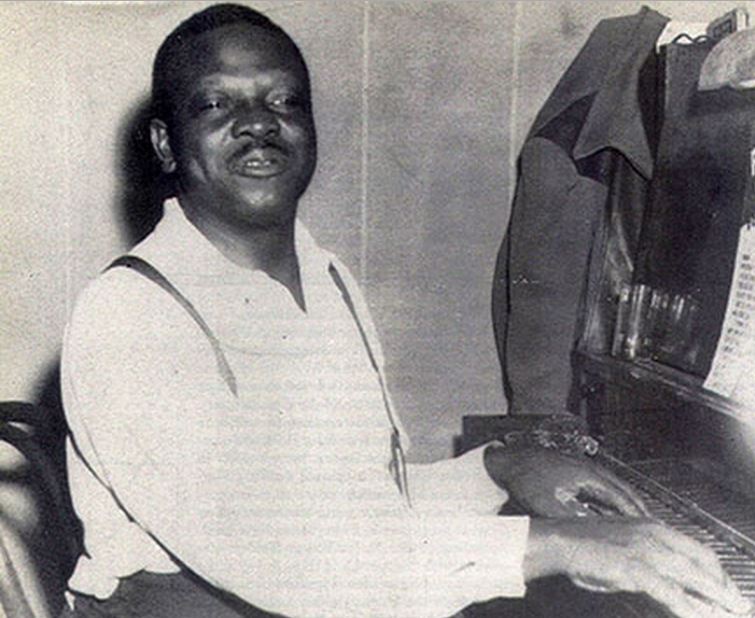

Oscar Holden, bandleader at the Patricia Cabaret and resident of 102 East Georgia Street. From the Grace Holden Collection

Oscar Holden, bandleader at the Patricia Cabaret and resident of 102 East Georgia Street. From the Grace Holden Collection

The Lincoln Club was a black social club during Vancouver’s jazz age of the late 1910s and early 1920s. It was located at 102 East Georgia Street, just west of Main, which means it was boxed in by the Avenue Theatre on the east and the original Georgia Viaduct on the north, and so was only accessible from below the viaduct or from the alley. During its six-year existence, the Lincoln Club took on the role of the city’s earlier railway porters’ clubs as an important social hub for Vancouver’s small black community and for performers passing through town on the vaudeville circuits.

The building that housed the Lincoln Club replaced an old horse stable around 1911. It was a brick building with nineteen rooms, each equipped with a service bell, hot and cold running water, and steam-heat. It was one of the many rooming houses, or Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels, built around that time. It was probably a bit fancier than most, as it was most likely intended to be a brothel in what was then the city’s “restricted district.” Not long after it was erected, the red light district was pushed from Shore Street (as the 100 block of East Georgia was then called) to Alexander Street, where a few purpose-built brothels have survived as low-income housing. Construction of the first Georgia Viaduct, practically on its front doorstep, began in 1913 and no doubt made the value of the property plummet. The building was listed for rent in January on “easy terms,” and then for sale in March. “Will sell cheap,” says the ad.

In 1916, 102 East Georgia was owned by a miner named Charles Alexander who spent $1000 on a brick extension to the building. The first time the name “Lincoln Club” appears is when the phone line was installed in 1917. Alcohol prohibition came into effect later that year and kicked off Vancouver’s “jazz age.”

1913 insurance map showing the Lincoln Club building in red. Courtesy City of Vancouver Archives

1913 insurance map showing the Lincoln Club building in red. Courtesy City of Vancouver Archives

The most notable resident of 102 East Georgia was Oscar Holden, the band leader at the Patricia Cabaret, the hottest jazz venue in town at the time. Holden later moved to Seattle and helped pioneer that city’s much larger and more viable jazz scene on Jackson Street. “Anything you set before him, he’s gone!” recalled a fellow Seattle musician. "He had a wonderful musical education. He was a great, great performer.” It’s unimaginable that other performers from the Patricia and other venues in town didn’t stop by the Lincoln after hours to jam, dance, gamble, and drink into the night, including George Paris, Ada Bricktop Smith, and Jelly Roll Morton.

The Lincoln Club was run by Reg Dotson, a black man born in Missouri. Dotson often hosted acts passing through town, according to reports in the Chicago Defender, an important African American newspaper in the post-WWI period. The comedy duo Green and Pugh noted in a letter to the paper that “Reginald Dotson, who owns the finest club in Vancouver, was waiting at the pier for us in his big car, and that is the way we have been treated since leaving Chicago.” Tom Clark, described by the Defender as “well known to members of the profession,” reported in 1919 that he was now living in Vancouver and that mail could reach him at 102 East Georgia. A month later, a correspondent living at 940 Main Street, noted that “Tom Clark has a neat little cafe.” L Louis Johnson wrote in and said that while visiting Vancouver in 1921, “we dined with Reggy [Dotson] at his palatial home and Oh, such a meal.” Joe Sheftell, manager of the vaudeville act the Creole Fashion Revue, said that “Reggie Dotson gave a banquet last night and we had everything from soup to nuts.” In 1922, ET Rogers of 804 Main Street informed the Defender that “Vancouver is still on the map … The Lincoln Club is still headquarters. It is the best club on the coast.” Another 1922 Defender report noted that the “Lincoln Club gave its annual breakfast dance Easter Sunday.”

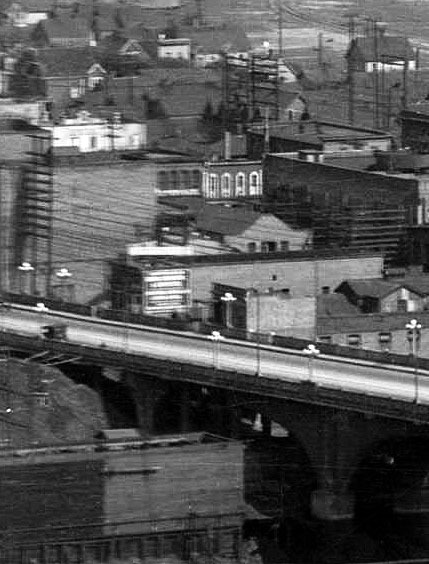

The only image of 102 East Georgia (centre) I found that was taken while the Lincoln Club was still operating. Detail of WJ Moore panorama, June 1921, CVA #PAN N221

The only image of 102 East Georgia (centre) I found that was taken while the Lincoln Club was still operating. Detail of WJ Moore panorama, June 1921, CVA #PAN N221

Vancouver’s (white) press, meanwhile, painted a picture of the Lincoln Club as nothing more than a disorderly house. The first of only two incidents that earned Dotson and his club coverage in the local papers was a police raid in December 1919. “Among the colored members four white girls were found,” reported the World. Dotson was fined $50 plus costs for keeping a gaming house and $300 for “having liquor illegally in possession” under the Prohibition Act. Thirty-nine “inmates” found in the joint were each fined $15 plus costs. We can only imagine how the presence of white women influenced the case.

The second incident involved the head inspector of the Liquor Control Board trying to extort $50 from Dotson, but who got off by claiming he was trying to nail after-hours clubs that were paying off the police. His court room defense emphasized that the Lincoln Club was one of the most prolific violators of the Liquor Act and highlighted the presence of white women in the club.

102 East Georgia was listed as “vacant” in 1925. Reg Dotson died ten years later.