In 2018, an American missionary named John Allen Chau was killed by the Sentinelese tribe, which exists mostly as it has for thousands of years on the remote island of North Sentinel.

The incident brought global awareness to the existence of human beings who continue to live as people did for millennia, unaware of space shuttles, inkjet printers, Instagram, and stock market downturns.

The Sentinelese are notoriously hostile to outsiders—and for good reason. The rise of agriculture and permanent settlements 12,000 years ago ushered in an era that has not been kind to the world's Indigenous populations, especially the last few centuries of industrialization, global exploration, and trade, which have extinguished virtually all traces of the world that came before.

A few small and isolated tribes, however, have resisted modernity and remained frozen in time. They're scattered around the world, but the vast majority live in South America, mostly in the Amazon region.

Although virtually no one on Earth has had no contact with outside society, the most isolated people are classified as "uncontacted." Some fled into forests centuries ago to escape conflict, others broke off from larger groups and established their own tribes, and others experienced contact but then retreated back into the wilderness.

All, however, have one thing in common: vulnerability. With each passing year, their lands and numbers get smaller as the industrialized world's relentless expansion drives them deeper and deeper into refuges that offer fewer and fewer places to hide from the tide of change.

Jesse Allen/NASA Earth Observatory // Wikimedia Commons

Sentinelese people of North Sentinel Island

The remnants of a 60,000-year-old tribe whose members are direct descendants of the earliest humans in Africa, the Sentinelese are probably the most isolated people on Earth, living where they always have on North Sentinel Island in the vast Bengal Bay. The last major contact with the group came in the late-1800s when a British Royal Navy explorer kidnapped people in the tribe, subjected them to bizarre sexual experimentation, and introduced diseases that decimated their population. Little is known about them, and contact is forbidden with the tribe, which remains ferociously hostile to visitors.

Jarawa people of the Andamanese Islands

North Sentinel is part of the Andamanese Islands, which is also home to another ancient people, the Jarawa, who have been living there for 55,000 years. Their quest to remain untouched by modernity, however, has not been as successful as that of their Sentinelese neighbours, though some small groups of the 400-strong nomadic tribe do still remain uncontacted.

Although India's Supreme Court halted construction in 2002, corporations built a section of highway through Jarawa land, which continues to attract poachers, drug dealers, and, most disturbingly, "human safari" tourists hoping to catch a glimpse of the prehistoric hunter-gatherers.

Awa of the Amazon

Illegal logging, deforestation, and other encroachment have made the Awa among the most vulnerable uncontacted tribes on Earth.

The Amazon rainforest that straddles the border of Peru and Brazil has supported the Awa for millennia, but today, only about 60-80 of the roughly 600 remaining Awa still live nomadic, uncontacted lives that depend solely on the bounty of the land. The rest live in isolated and protected jungle villages.

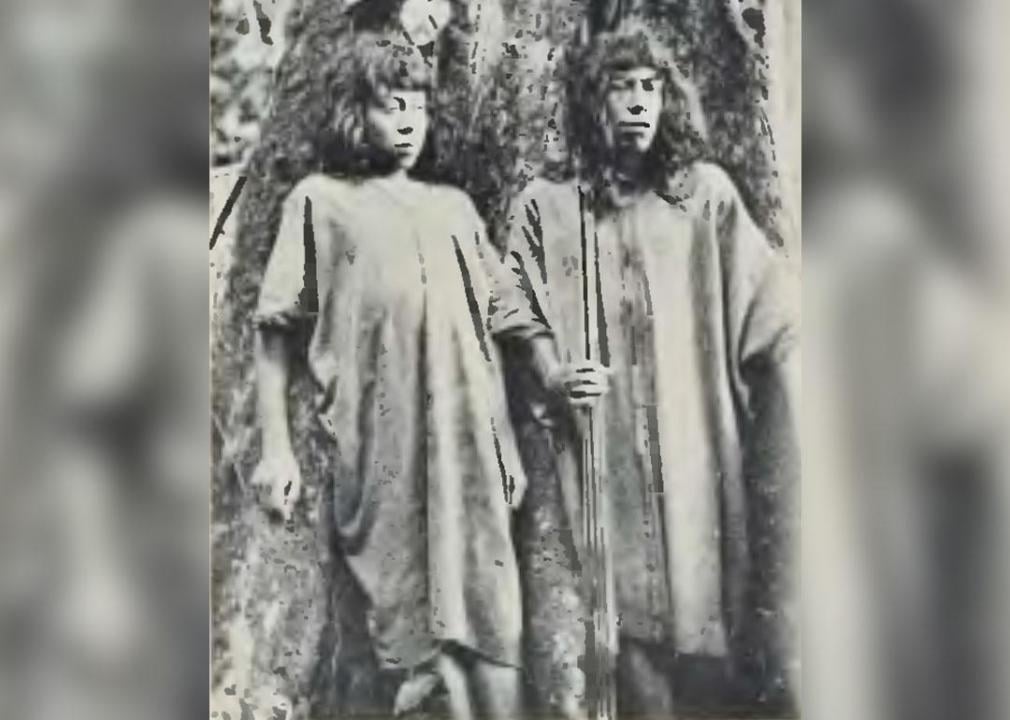

Teobert Maler // Wikimedia Commons

Lacandon of Mexico

Deep in the Lacandon Rainforest of southern Mexico and northern Guatemala, the Lacandon people still exist, some of them uncontacted and isolated deep in the vast forest. Now numbering fewer than 1,000, the Lacandon are descended from Maya people who fled to the jungle interior in the wake of the Spanish conquest.

Ángel M. Felicísimo // Wikimedia Commons

Yuqui of Bolivia

The Yuqui were originally contacted by the Spanish in the mid-16th century but were then left isolated from modern society for more than 400 years until the 1960s. They were at that time thought to be part of a larger group called Siriono, but through their unique language, also called Yuqui, the Yuqui people were determined to be a distinct tribe. Although they once ranged over a large part of the Bolivian Lowlands, the known population now numbers roughly 130, although it is likely that some remain uncontacted and uncounted.

LiadePaula/MinC // Flickr

Wajãpi of Brazil and French Guiana

Wajãpi is the name given to a group of Indigenous people who speak the Tupi language and live in a range that straddles the border between Brazil and French Guiana. They are scattered among smaller groups called "kin," which, depending on which side of the border they live, have had varying degrees of contact with outsiders.

David Lazarus // Wikimedia Commons

Ayoreo of Paraguay

The pristine wilderness that is the Paraguayan Chaco region has long been the range of the Ayoreo people, but it is now suffering the fastest rate of deforestation on Earth.

Many Ayoreo have been contacted since the first Mennonite farmers established colonies there in the 1940s and 1950s, but some still remain isolated. Their hiding places, however, grow smaller and fewer every year as foreign ranching companies buy their land and destroy the forest to make vast clearings for cattle.

Fotografías Nuevas // flickr

Totobiegosode of Paraguay

Paraguay's Totobiegosode people are a distinct offshoot of the Ayoreo, but they are even more isolated from modern society—their name means "people from the place of the wild pigs."

These last survivors live life mostly on the run from bulldozers and hostile cattle ranchers. Even still, some have managed to retain a nomadic lifestyle and avoid all contact with the outside world, even though efforts to modernize or remove the Totobiegosode have forced large numbers of them from the forest.

Palawan Island tribes of the Philippines

About 40,000 Indigenous people live in the southern portion of Palawan Island in the Philippines. Despite significant encroachment from mining and the thousands of settlers the industry has attracted, some tribes deep in the interior remain virtually uncontacted. Among them are the Tau't Bato, who reportedly live in caves in the crater of an extinct volcano.

Yuri and Carabayo of Colombia

In 2012, Cristóbal von Rothkirch of the Colombian National Parks Unit and Amazon Conservation Team took photographs that prove the existence of uncontacted people living in the remote rainforest on the border of Colombia and Brazil. The photographer documented five longhouses called malokas, traditional structures built by both the Carabayo and Yuri tribes, deep in the Rio Puré National Park.

The Taromenane of Ecuador

Exceptional and isolated even by the standards of uncontacted Amazonian tribes, the Taromenane live in an especially remote and inhospitable patch of jungle. They never lived in large groups, so unlike most uncontacted people, the surviving Taromenane are not a small remainder of what was once a larger tribe, but a close representation of how the group has existed for centuries.

kate fisher // Wikimedia Commons

The Huaorani of Ecuador

About 200 uncontacted people are believed to still exist in the jungles of Ecuadorian Amazonia. Some are Taromenane, but others belong to a rival tribe that the Taromenane continues to engage in often violent conflicts to this day: the Huaorani. Some of the Huaorani have engaged with the modern world—to the point that some of them bragged on national television about a massacre of Taromenane, but others remain almost totally isolated.

Jonathan Lewis // Wikimedia Commons

The Tacana (Toromonas) of Bolivia

In 2016, reports emerged that Bolivia's national oil company hid evidence that its prospectors had encountered uncontacted people near the Peruvian border. That tribe was most likely the Tacana people, sometimes called Toromonas.

Oil prospectors exploring the remote interior jungle found footprints and empty tortoise shells, heard shouting in the forest, and later had their camp surrounded by indigenous people. The company allegedly covered up these events because the discovery of uncontacted people would have forced them to stop their oil work.

Piripkura of Brazil

Anthropologists are aware of a remote, isolated tribe known to their settled indigenous neighbours as Piripkura, or butterfly people, a nickname earned for their frequent flight through the forest.

Brazil's indigenous affairs agency contacted the Piripkura for the first time in the 1980s, and the group retreated back into the forest soon after. There were about 20 of them at the time, all of whom spoke the Tupi-Kawahib indigenous language. Three members of the tribe have contacted outsiders in the ensuing years, and one man later emerged from the forest seeking medical attention and describing a massacre by white people.

Gleilson Miranda / Governo do Acre // Flickr

The Acre tribes of Brazil

The uncontacted groups concentrated in the Acre state of Brazil are ferociously independent and hostile toward outsiders, with some spotted shooting arrows at intruders and even at passing airplanes. The hostility is likely a result of their lineage. The Acre tribes are likely the survivors of the bloody South American rubber boom, during which countless indigenous people were slaughtered or enslaved in the rubber trade and worked to death. Only some escaped into the jungle to form new tribes.

JialiangGao // Wikimedia Commons

Nukak of Colombia

The Nukak are perilously endangered—one of the 32 tribes in Colombia designated as facing "imminent risk of extinction," according to Survival International. It wasn't until 1988 that the Nukak emerged from almost total isolation when roughly 40 of them created a media sensation by showing up at a remote colonist town near their lands. Half of the entire tribe soon died of measles. The survivors continue to face near constant encroachment from drug organizations and paramilitary groups involved in various Colombian armed conflicts.

West Papuan tribes

West Papua is the western half of the island of New Guinea, one of the most remote and inaccessible places on Earth. Governed by ethnically separate Indonesia, West Papua is home to a rich diversity of more than 300 tribes, a small number of which are believed to be uncontacted. Tribes there are subject to harsh, discriminatory treatment from the Indonesian authorities, who frequently harass, arrest, and kill tribespeople, or who aid and protect the companies that encroach on tribal lands to exploit the region's vast resources.

eGuideTravel // Flickr

Yaifo of Papua New Guinea

In 2017, explorer Benedict Allen disappeared for three weeks before re-emerging from one of the most isolated regions on Earth: the East Sepik jungle region the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, which occupies the eastern half of the island of New Guinea. He was searching for the Yaifo tribe, which has had so little contact with modern society that it has reached near-mythical status since Allen himself established first contact with the tribe 30 years earlier.

Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil // Wikimedia Commons

Kawahiva of Brazil

The Kawahiva are among the most endangered tribes in the Brazilian rainforest. The government's indigenous affairs agency last reported their group to number about 50, although very little is known about their lifestyles and customs. They are believed to have stopped having children because they are in near-constant retreat from logging workers and other intruders.

Fionashek22 // Wikimedia Commons

Korubu of Brazil

The Korubu is one of seven uncontacted tribes living in the Javari Valley on the border of Brazil and Peru. There are also seven contacted tribes, which makes the region home to one of the highest concentrations of isolated people on the continent. In 1996, a government agency made contact with about 30 Korubu—who are known for carrying large fighting clubs—who had split off from the main group, which remains uncontacted and uncounted.

Massacó territory tribe of Brazil

Roughly 300 uncontacted Indigenous people still live in the Massacó territory in the Brazilian state of Rondônia. It is believed that tortoises are a large part of their diet as explorers have found mounds of empty tortoise shells. They are also believed to use gigantic bows and arrows, with one bow found measuring four meters (13.12 feet) long.

Corey Spruit // Wikimedia Commons

Mascho-Piro of Peru

For the last 40 years, Peru's estimated 600-800 Mascho-Piro tribespeople have had some contact with settled indigenous people in the Amazon region, but virtually no exposure to outsiders. That has recently begun to change.

Starting around 2015, Mascho-Piro people have emerged from the forest and—in a reversal of their longstanding policy of voluntary isolation—have initiated contact with outsiders, sometimes with disastrous results. Despite this shift, many remain uncontacted.

Chany Crystal // Flickr

Peru's refugee tribes

In June 2014, seven sick and desperate members of an unknown and uncontacted tribe from Peru made contact with a group of settled indigenous people in the Acre region of Brazil, near the border of the two countries. After receiving medical treatment, they returned to the forest. Later that summer, a much larger group of about two dozen people from the same Peruvian tribe emerged and reported being attacked by unknown invaders.

Sam Valadi // flickr

The Moxateteu of Brazil and Venezuela

The 35,000-strong Yanomami tribe is the largest group of relatively isolated people remaining in South America. They have lived in the rainforests of Brazil and Venezuela for thousands of years, but are now facing the same threats of encroachment and deforestation that challenge all isolated people.

The Yanomami are also keenly aware of another group living in the forest: the Moxateteu, which is the tribe's name for uncontacted Yanomami who roam even more remote and isolated parts of the jungle.

Planet Labs, Inc. // Wikimedia Commons

Cacataibo tribe of Peru

The Cacataibo tribe is one among what experts believe to be 15 uncontacted groups living in Peru. Although the government has established protected areas for them, the vast majority of the region they inhabit has been sold to oil and gas concessions, as well as mining and logging operations that threaten their existence with disease and habitat destruction.

Internet Archive Book // flickr

Matsigenka tribe of Peru

Little is known about the Matsigenka people, who live virtually uncontacted in the same part of Peru as the Cacataibo tribe. What is known, however, is that they have retreated to an increasingly small and remote enclave within their protected area, as energy and logging companies threaten their existence. Without intervention, they are likely to soon disappear entirely.

James Martins // Wikimedia Commons

Isconahua people of Peru

The Isconahua people live isolated on a patch of protected rainforest that remained virgin jungle unseen by outsiders until the 1950s. They are known to migrate seasonally in search of resources. In the rainy season, they inhabit large houses but move toward the beaches, rivers, and streams in search of water and tortoises to eat during the dry season.

Gleilson Miranda / Governo do Acre // Wikimedia Commons

Chitonahua and Murunahua people of Peru

The Chitonahua and Murunahua people are believed to be living largely uncontacted on the Murunahua Territorial Reserve in Peru. The contact they have endured, however, has not been beneficial—they are believed to number fewer than 50.

Planet Labs, Inc. // Wikimedia Commons

Akuntsu of Brazil

In the state of Rondônia in Western Brazil, the last four surviving members of the Akuntsu tribe eke out an existence from what little game exists in the tiny patch of rainforest they inhabit—the last scrap of what was once an immense jungle that's been annihilated to make way for cattle ranches.

Although no outsider has mastered the Akuntsu language, the government protected the land where the survivors were hiding upon learning that their entire society was massacred by ranchers, loggers, miners, and other intruders after the building of a highway in the 1970s opened their lands to incursions of all kinds.

YouTube

The Man of the Hole

The most endangered uncontacted tribe on Earth has to be the one that belonged to the so-called "Man of the Hole." He is the sole survivor of a massacre that rendered him the last of a tribe from the Amazon rainforest that anthropologists know almost nothing about.

The government has set aside a small patch of rainforest for the man—who got his name from the holes he digs to hide in and to trap animals—who lives completely alone, refuses all contact, and whose patch of forest is surrounded on all sides by the cattle ranchers that likely killed his people.