The B.C. government says it has invested more than $3.5 billion since 2018 to expand and improve “quality care” for seniors, including investments in primary care, home health, long-term care, assisted living and respite services.

The ministries of housing and health provided the information in a lengthy emailed response to Glacier Media’s questions related to shortages in Vancouver of subsidized long-term care beds, assisted living units and seniors’ affordable housing.

“We are working to ensure that B.C.’s growing and aging population has the support they need, when and where they need it,” the ministries said Monday in the email.

In a city where the fastest growing age demographic is seniors, Vancouver will have a shortage of more than 300 subsidized long-term care beds and 90 assisted living units in 2025.

That data was supplied by Vancouver Coastal Health to City of Vancouver staff to assist them in the development of the city’s first-ever seniors’ housing strategy, which council approved in July.

“This shortage could grow to close to 1,500 long-term care beds and 350 assisted living units over the next 10 years due to demographic changes,” said the authors of the strategy, which outlines the state of seniors in Vancouver.

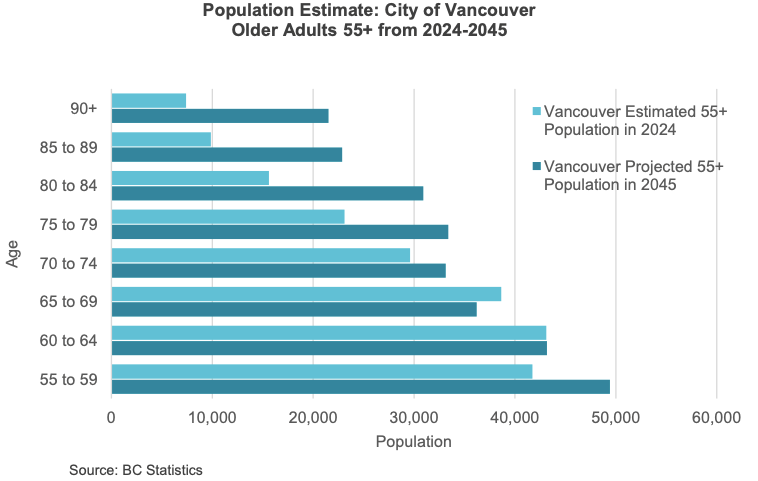

More than 194,000 Vancouver residents are 55 years or older, and account for 30 per cent of the city’s population. That number is expected to increase significantly over the next 20 years.

Seniors are also getting older as a cohort, with higher proportions of people aged 75 and older in the coming future, according to the strategy, which provides a long list of challenges facing seniors, including waitlists for subsidized housing.

In 2023, about 43 per cent of people — or 2,420 persons — on the social housing waitlist in Vancouver were 55 or older. From 2022 to 2023, the number of people on the waitlist increased by 18 per cent, the largest increase seen in recent years.

'Replacement beds'

In response, the ministries said government has expanded and developed many long-term care homes around B.C., reducing multi-bed rooms and increasing long-term care capacity around the province.

The government identified four projects in Vancouver, where a mix of “replacement beds” and new beds totalling 631 were either opened in 2023 or will be completed in 2028. The net gain in beds for the four projects will be 182.

Since January, the government says it has announced funds for eight long-term care projects across the province — from Richmond to Quesnel — totalling 1,134 beds. No completion dates were provided.

In addition, the government — via its community housing fund — opened the North Arm Housing Co-operative in Vancouver at East 19th Avenue and Fraser Street in September 2023.

The 58-unit, six-storey building is a mix of studio and one-bedroom apartments home to single people and couples 55 and older, who pay on average $800 to $1,400 per month in rent.

The $20-million North Arm project was the result of a partnership involving the City of Vancouver (which owns the land), the B.C. government (which provided $10.8 million) and the Community Land Trust of B.C. (which holds a 60-year lease on the land and manages the building).

SAFER program

One of the many concerns highlighted in Vancouver’s seniors’ housing strategy was the inadequate rent subsidies available to seniors under the province’s Shelter Aid for Elderly Renters (SAFER) program.

The authors of the strategy acknowledged the provincial government’s announcement in April regarding improvements to the SAFER program, including a one-time payment of $430 for those already receiving the rent subsidy.

The government has also increased the income limit for eligibility from $33,000 to $37,240. The authors described the changes as “positive,” but said for older adults who had to move in recent years and have near-market rents, SAFER remains inadequate.

If the SAFER formula was updated to work for older adults renting in Vancouver, with a rent ceiling of $1,786 to match the average one-bedroom rent in 2023 — and an income limit of $45,000 to meet the average incomes of those overpaying on rent — “it would create immediate affordability for those in urgent housing need and at risk of homelessness,” the authors said.

The case made by City of Vancouver staff is that if such a change was made, it would cost the province approximately $25 million annually. That money would reach more than 4,900 seniors with incomes below $45,000 who pay more than 30 per cent of their household income on rent in the private market.

'Preventing homelessness'

The $25 million would be a significant increase from the $8.5 million SAFER subsidies distributed to Vancouver seniors in 2023.

“However, the costs of creating affordability in the existing market through SAFER remains significantly lower than the billions in funding and financing to build new social housing that would otherwise be needed,” the authors said.

“Further, this increase would reach low-income seniors now, improving overall health and well-being and preventing homelessness.”

The government’s response was that 4,800 more seniors now qualify for the SAFER program, which already subsidizes 23,000 senior households in B.C.

“This builds off additional investments we made in 2018 under the SAFER program, where we expanded eligibility and increased monthly rental payment amounts by approximately 42 per cent,” the government said.

“We will continue to monitor the SAFER program and look for changes and improvements to further support seniors in need in B.C.”