In 1921, Canadian researchers discovered insulin, instantly changing the fate of diabetics around the world.

A hundred years later, over a half billion people around the world live with one form of the disease — a number the International Diabetics Foundation projects will climb to 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045.

But even if diabetics can access the insulin (the United Nations says almost half can’t), many — including 300,000 Type 1 diabetics in Canada — face painful injections before every meal.

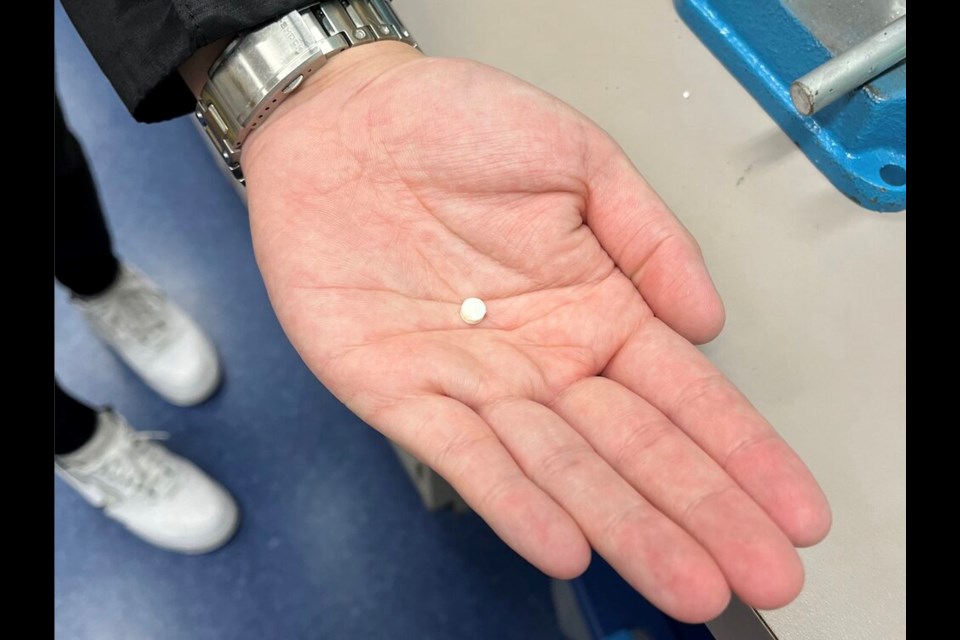

Now, researchers from the University of British Columbia say they have found a “breakthrough” that could do away with the needle: an insulin pill.

“We had no idea whether the formulation would even work,” said Anubhav Pratap-Singh, a researcher at the school’s faculty of land and food systems. “This is a proof of concept.”

In a study published in the Nature journal Scientific Reports, Pratap-Singh and his colleagues note that if an oral insulin formulation were successful, it could “bring the quality of life back” for millions — not to mention give the nearly seven million people who die of diabetes every year a better chance of survival.

To date, the promise of an insulin pill has faced a number of challenges.

Past attempts to create oral insulin have resulted in the medicine accumulating in the stomach instead of reaching the bloodstream and liver where the hormone regulates blood sugar levels.

To solve that problem, Pratap-Singh says his team avoided the gastrointestinal system altogether.

Their formulation starts with a cheap technique to convert suspended insulin into a stable powder. Known as spray drying, the solution is blasted through a hose and nozzle into a chamber. Inside, the water vapour evaporates, leaving nanoparticles of insulin locked in a protective coating.

From there, the dried insulin can be pressed into a tablet without heavy amounts of additives required under expensive freeze-drying techniques.

Most importantly, says Pratap-Singh, the UBC team's formulation dissolves in the mouth.

“We are bypassing the stomach,” said Pratap-Singh. “When you put it against your cheek, it goes directly to your blood.”

So far, the researchers have finished phase one animal trials. Next up are tests in larger mammals, like rabbits. If all goes well, Pratap-Singh says the first human trials could start within two years; within five, he said, “it could be available to the public.”

Part of Pratap-Singh’s motivation to develop an oral insulin pill comes from his father, who has spent years injecting insulin before every meal.

On a personal level, Pratap-Singh says he still can’t watch his dad inject himself, and he hopes a pill would eliminate that painful daily habit.

At the same time, he looks at countries like India, where his father lives, and sees a big gap in access to the medicine.

Transportation and storage add cost to already pricey insulin. But the biggest problem, he said, is that many don’t have electricity.

“Current insulin formulations have to be kept refrigerated,” said Pratap-Singh.

“This formulation will be shelf-stable.”