The number of break-ins to vehicles in Vancouver almost doubled in the last eight years, jumping from 7,266 incidents in 2011 to 14,598 last year, according to year-end statistics for 2018 released by the Vancouver Police Department.

That increase meant police received an average of 40 break-in reports per day in 2018 as compared to an average of 20 per day in 2011, when the crime was at its lowest in the past decade. In 2009, there were 9,721 incidents and 8,385 in 2010.

Car break-ins in Vancouver have doubled over the last eight years. Photo via iStock.

Car break-ins in Vancouver have doubled over the last eight years. Photo via iStock.

The statistics were released in a year-end police report on crime trends for 2018 that goes before the Vancouver Police Board Feb. 21. The report doesn’t explain the reason for the increase in thefts from vehicles.

The Courier was unable to reach anyone at the Vancouver Police Department to comment before deadline. Police, however, have previously connected the crime to drug-addicted people looking to steal cash or valuables to exchange for drugs.

“A lot of these are crimes of opportunity,” Police Chief Adam Palmer told the Courier in an interview in 2016. “So people will be walking down the street trying doors, they’ll be looking in cars. If they see anything of value, if they see some loonies and toonies and quarters in your cup holder or something, they’ll break into your car to steal that.”

Palmer and his predecessor, Jim Chu, have repeatedly called for treatment on demand for drug users. Vancouver is not a city “where if somebody is addicted to drugs and they need help and they come forward to a police officer or just want to self-report and get help, they don’t have anywhere to go,” the chief said.

As the VPD’s 2019 strategic business plan notes, police will continue to run targeted enforcement projects — specifically going after chronic offenders — and campaigns to educate the public on how to deter or prevent vehicles from becoming targets of criminals.

Police have also partnered with health officials, the courts, business associations and government to support ways to reduce the drivers of drug addiction, including mental health, poverty and homelessness.

The work continues to be a challenge as homelessness reached an all-time high in the city last year, with 2,181 people counted as homeless in the city’s count.

Police calls where an officer used the Mental Health Act to arrest a person or take someone to a doctor for examination increased from 2,822 in 2016 to 2,883 last year. Those types of calls reached an all-time high of 3,050 in 2015, but were significantly lower in 2010 at 2,278 calls.

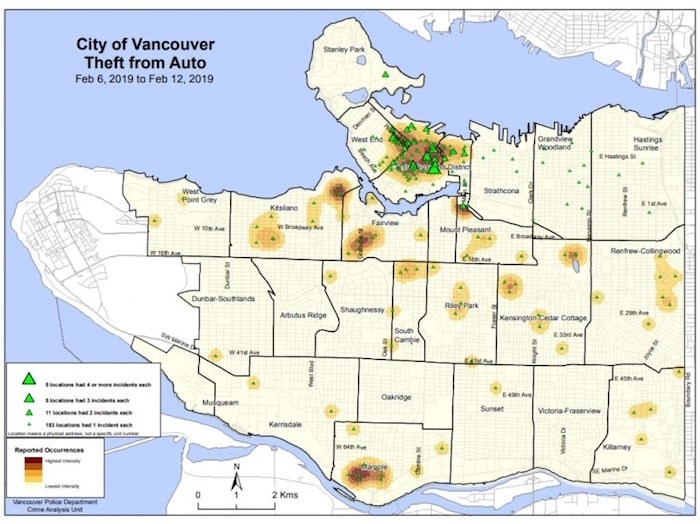

Graphic via VPD

Graphic via VPD

Break-ins to vehicles occur across the city, but the VPD’s most recent “crime heat maps,” which cover the period from Feb. 6 to Feb. 12, show the largest concentration of thefts occurred downtown.

It’s a fact that concerns Charles Gauthier,president and CEO of the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, who said it’s probably time to consider other alternatives to combatting the crime of thefts from vehicles.

Police enforcement, patrols by the DVBIA’s Downtown Ambassadors and education campaigns can only go so far, he said, noting such efforts have seen positive results but pointed out the root of the problem persists: drug addiction and the need for users to feed their habit.

“We may be at the point where we may need to look at other options, which is providing people with access to the drugs that they need and taking the wind out of the sails that’s fueling the property crime,” Gauthier said of a growing campaign by health officials, Mayor Kennedy Stewart and others in harm reduction fields to push for a clean supply of drugs for users.

Gauthier said the business association is not at the point where it wants to launch a campaign to encourage people to choose transit over a car when travelling into downtown. He noted vehicles are also being broken into in other neighbourhoods, where there isn’t the concentration of cars.

“If you’re a victim of a theft from auto, it really doesn’t matter that there’s proportionally more people parking downtown,” he said. “On an individual basis, it’s an awful experience to go through.”