The push for a North Shore college culminated in a successful plebiscite in the spring of 1968. photo supplied Capilano University archive

The push for a North Shore college culminated in a successful plebiscite in the spring of 1968. photo supplied Capilano University archive

She was renting a pioneer shack in Lower Capilano for $50 a month when the campaign stirred to life.

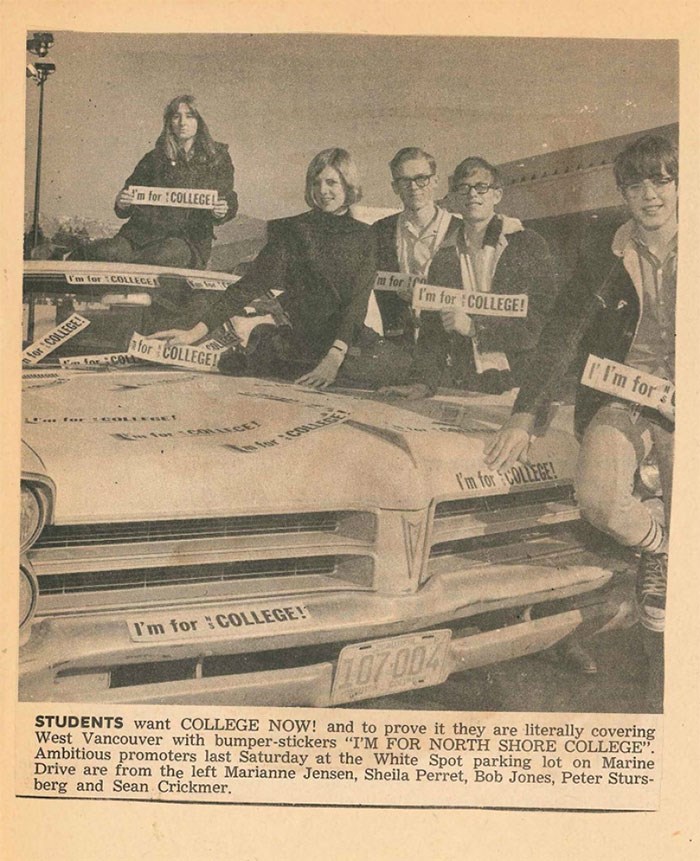

It was a typical ad campaign with bumper stickers and mailouts. The product being sold, however, was unique: the first North Shore college.

Nobody knew what to call it or where to put it, but in the spring of 1968 the smile-on-your-brother-everybody-get-together generation was tuned in and turned on to the idea.

A newspaper photo from that season captures impossibly young-looking people splayed on the hood of an impossibly enormous Oldsmobile, all of them grinning and bearing the slogan: I’m For N.S. College!

Jane Rawson was not among those young people.

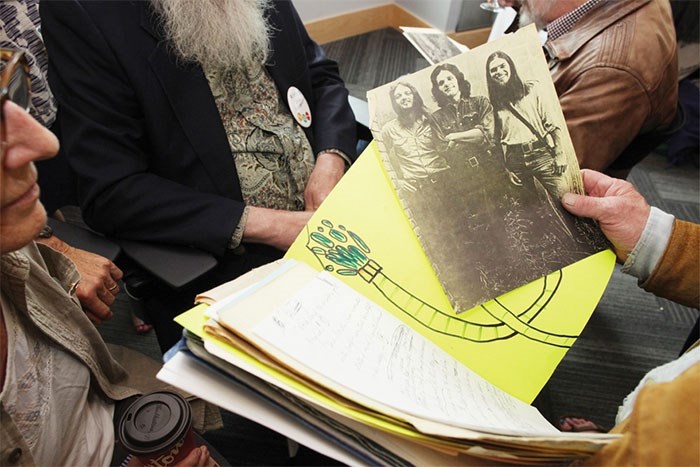

On Sept. 10 of this year, Capilano University hosted a soiree for the school’s first staff and students. Over white wine and fresh fruit the conversations veered from hiring the Guess Who to play the school (“I was on security and got my nose broken,” Don Plumb reports) to college retreats where students strummed guitars and drummed pots and pans while forming connections that would last half a century. There were also memories perhaps too sweet to be spoken aloud.

Students and teachers leaf through scrapbooks while trading stories about the bands they saw and the injuries they sustained – photo Lisa King

Students and teachers leaf through scrapbooks while trading stories about the bands they saw and the injuries they sustained – photo Lisa King

“I don’t remember anything,” Bob Morris reports. “It was 1968.”

Rawson’s recollections are different.

“I didn’t go to those retreats,” she offers. “I didn’t form many connections.”

Raising her child in a dilapidated shack, college days seemed to have passed Rawson by.

But all that changed on March 7, 1968. A plebiscite on the formation of the college was held and a majority of North Shore residents decided they’d be willing to pay an extra $7 in property tax if it meant their kids could go to college closer to home.

The ad campaign worked.

Rawson’s social worker told her she’d have to pay for her own books, but that welfare could cover the cost of tuition.

Initially, Capilano College was a night school, holding classes between 4 and 10:30 p.m. in church basements, a warehouse and a bowling alley, recounts Chuck Davis in the History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Mostly, however, the students filed into West Vancouver Senior Secondary School.

It wasn’t exactly perfect, for Rawson. But it was suddenly possible.

Students and teachers leaf through scrapbooks while trading stories about the bands they saw and the injuries they sustained – photo Lisa King, North Shore News

Students and teachers leaf through scrapbooks while trading stories about the bands they saw and the injuries they sustained – photo Lisa King, North Shore News

“It was a thing I could do because it was in the evenings,” she emphasizes.

Through social assistance and a temporary job surveying North Shore residents about the need for a third crossing, Rawson was able to hire a babysitter, rush out, rush home, raise her child, study and survive, she says.

“It was a lonely, tough life.”

But thanks to some “fantastically inspiring” teachers, Rawson embarked on post-secondary education beyond Cap, eventually getting two degrees in art and securing a teaching position at SFU’s interactive arts program, she reports.

“We made that into a kickass first-year program,” she recalls, flashing a grin.

It all started in a college that opened with everything but a building.

Where do you want me to put this thing?

There was an idea, explains one-time student society president Don Plumb, to take a “rusty old aircraft carrier that’s full of toxic crap,” park it at the mouth of the Capilano River, and turn Capilano College into Canada’s first marine college.

“The students came back, almost unanimously, on this ex-American aircraft carrier that was available for $1 million,” he says. “Of course it was very impractical.”

About a month after the plebiscite, the college was dubbed Capilano, which won out over suggested names: Alpine, West-Van Bay, and Martin Luther King University.

But while the school had been approved, the demand from students hadn’t really been gauged, according to Tim Hollick-Kenyon, who served as registrar in that first year.

“We didn’t know what we were doing,” he says. “Everything was new.”

Original faculty member Bill Schermbrucker and former student Brad Ewing trade notes on old times at a party that celebrates the school’s journey from idea to college to university – photo Lisa King, North Shore News

Original faculty member Bill Schermbrucker and former student Brad Ewing trade notes on old times at a party that celebrates the school’s journey from idea to college to university – photo Lisa King, North Shore News

Unsure what to do for a registration system, Hollick-Kenyon reports visiting a colleague at Simon Fraser University and grabbing a pile of their forms.

“I crossed out Simon Fraser and put down Cap College,” he says proudly.

They planned for 300 students; 578 registered in the first week. By the first day of classes there were 784 Capilano College students, approximately 40 per cent of whom, Hollick-Kenyon notes, were mature women.

It was only a matter of time before the college was too big for a high school.

A 1969 study recommended putting the college near Capilano Lake near the base of Grouse Mountain, or on the Blair Rifle Range, which at the time was believed to be relatively mortar-free.

The college shouldn’t be located too far to the east, or in too remote a location, the report suggested.

“West Vancouver people do not often penetrate far into North Vancouver, either for social or commercial purposes. ... If the college is to develop as a community focus, it must be located at least on neutral ground.”

“Perhaps the most nebulous and yet at the same time the most important factor,” the report noted, was the impact on traffic.

Given that the North Shore was served by two bridgeheads “with a third crossing in the planning state,” the 1969 study notes that students who drive would reach college “much more rapidly and easily than by any other conceivable mode of transportation.”

A second study recommended the Capilano River zone, with “the West Vancouver dump site considered as a second choice,” the report adds, referring to a then-recently closed 17-acre landfill.

Despite concerns about portable units that would “resemble post-war UBC with its bric-a-brac shanty shacks littering the campus,” the college and the District of North Vancouver reached an agreement on 34 acres at Lynnmour, following a July public hearing that was “jammed with empty seats,” according to a Citizen newspaper article.

Ultimately, the college building opened its doors in 1973, eventually closing a deal to buy the site from the District of North Vancouver for $4,205,225.

What are you rebelling against?

“Whatdya got?” Bill Dodds finishes, reciting Brando’s famous line from The Wild One. “That was us.”

Dodds’ face alights as he recalls the “palace coup” that saw him terminated as editor of the student newspaper.

The college’s newspaper and steering committee occupied a single basement office.

The reporters would type whatever the steering committee said on the other side of the partition and put it straight into the newspaper, Dodds recalls. He pauses a moment to muse: “This annoyed them somehow.”

Capilano University commissioned the creation of nine murals on campus to celebrate the school’s 50th anniversary – photo Mike Wakefield, North Shore News

Capilano University commissioned the creation of nine murals on campus to celebrate the school’s 50th anniversary – photo Mike Wakefield, North Shore News

Dodds says he owes his education to a scholarship that covered three-quarters of his tuition costs.

“My parents were lower middle class. I didn’t want them to have to spend a lot of money on my education but everyone in the family was determined that I had to go to university.”

The Capilano University coat of arms features two winged bears holding a shield emblazoned with a leaping salmon and topped with thick books. The choice of bears over cougars and crows is explained in a 10-year-old internal document that explains: “In medieval bestiaries, bears were said to give shape to their own young, and therefore bears can represent the ‘forming’ of the young, a metaphor for education.”

There were some duds among the teachers, Dodds says, remembering students’ eyelids slipping downward during lectures from a psychology instructor. But, he adds: “If you stayed awake, you learned.”

But the best, he explained, was a history teacher who asked their students to “use their imagination on the past.”

“What an inspiration. Because as soon as you start to do that, you start to see the way things might have gone or should have gone. You can’t see it otherwise,” he says. “You’d go away with your brain on fire.”

The school developed its coat of arms after being granted university status in 2008 – image supplied Capilano University archives

The school developed its coat of arms after being granted university status in 2008 – image supplied Capilano University archives

Like a thumb-print cookie and teacup poodles, the college’s charm lay in its small size, Dorte Froslev explains.

“You felt taken care of in a way that you never would’ve at UBC,” she says.

Froslev, an owner of the Brackendale Art Gallery and a former art teacher at West Van High, praises the “full-spectrum” art program once offered at Cap.

“I sent lots of students here for that art program,” she says. “They were all devastated when they axed it.”

At the celebration of the college’s first students, university president Paul Dangerfield thanked that first class and those first teacher that “threw that little college on your backs.”

“It just started from, really just nothing, and you took it to this great university that we have right now,” Dangerfield says.

But afterwards, Froslev can’t help but think of the host of programs cut from the school in 2013 to cover a budget shortfall.

There had been cuts before. In 1985 the college laid off 98 temporary and 14 full-time teachers, which faculty member Walter Stewart decried as “a serious depreciation of the community’s resources.”

But the loss of the art programs feels permanent, Froslev explains.

“They’ll never get that back,” she says. “The bigger you become, the more impersonal it becomes, and this little tiny college that was like a womb for us out of high school has grown into this big university campus. You can never go back to that wonderful little embryonic thing.”

But while the college has become a university, “that spirit has continued,” Dangerfield says. “We’re dreaming that same level.”

In the early 1970s, a Cap student sent a letter to the local paper, responding to claims of pot-smoking students and their “far out” teachers.

“The young generation has been brought up to be skeptical of authority, perhaps with good reason,” she wrote.

Looking around the little room, Dodds seems to appraise his former classmates, noting just what a half century of life and making a living can do to a person, especially someone who used to be a rebel.

His son, he says proudly, has been “in and out of jail” for political protests.

“Some of us haven’t given up. Most of us have . . . now we’re just waiting to die. But by golly, I haven’t.”