Every year, UBC’s campus erupts in bloom, from delicate cherry blossoms and magnificent magnolias to brightly coloured alliums and richly scented lilacs.

A gardener at UBC. Photo courtesy of UBC.

A gardener at UBC. Photo courtesy of UBC.

It’s not just the work of Mother Nature that’s responsible for bringing the university landscape to life. A dedicated staff of 35 gardeners, arborists and horticulturists, divided into five crews, work year-round to maintain the university’s 172 hectares of varied landscapes. It’s a responsibility that requires detailed preparation, intense physical work, and the ability to adapt and plan for the changing seasons and climate.

“We work year-round,” says Grazyna Rougeau, sub-head for the north end of campus, whose responsibilities include tending to the Rose Garden, Museum of Anthropology gardens, the flag pole and Mackenzie House, the president’s residence.

“During the growing season, we’re doing all aspects of looking after the lawns, the beds and the trees. And in winter, our priority is snow clearing, but we’re also pruning trees and renovating garden beds to improve the landscape for the next year. We never stop.”

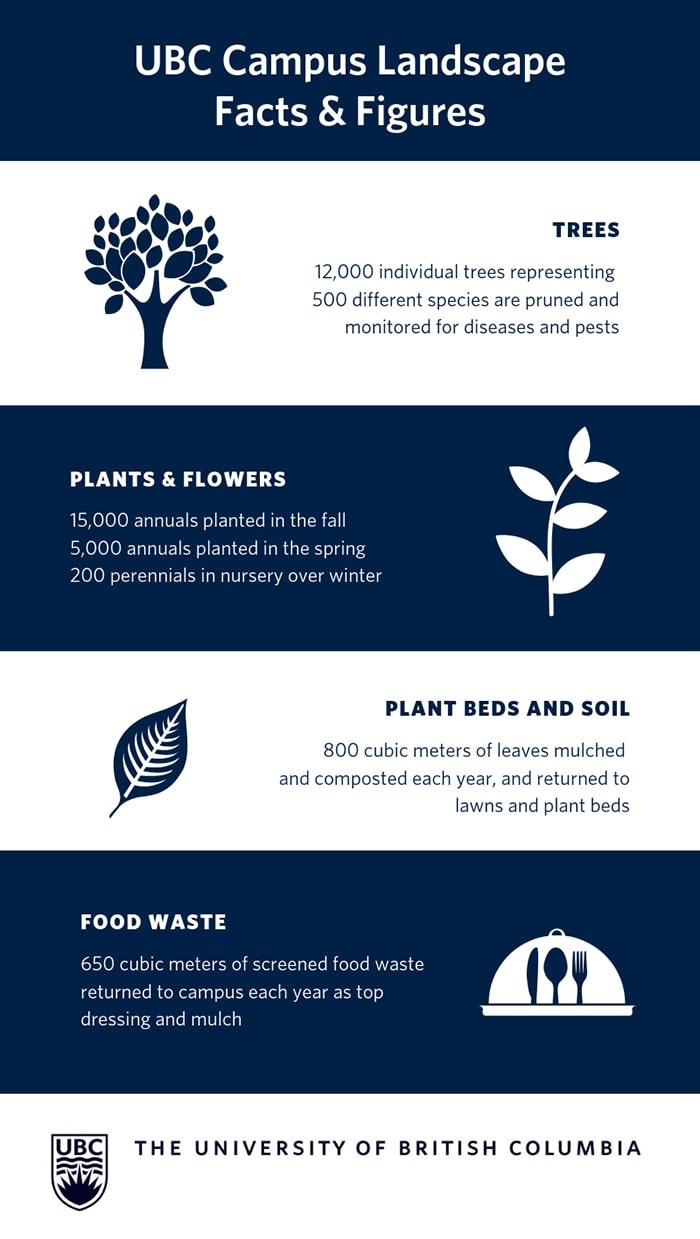

Collin Varner, arborist with building operations, has applied his expertise over three decades in stewarding and monitoring the health of our campus trees. He notes “there are over 12,000 planted trees on campus and over 10,000 native trees in their natural setting.”

A number of new plantings this year have found a home in Library Garden—the university’s newest green oasis, which houses the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. The space has been transformed from a previously poorly utilized area of the campus into a focal point, and was designed to meet the Sustainable Initiatives SITES framework—akin to a LEED designation for landscapes. Horticulturist Stacey Ewert has been managing and augmenting the site, establishing a range of indigenous plants, many of which are species used by the Musqueam people.

“It is all native species,” she says, gesturing to the young bushes and shrubs she has recently planted in the ground. “There’s red and black huckleberry, thimbleberry, elderberry—there are a lot of edible and medicinal plants.”

https://youtu.be/cc1r8Ky8FMY

When developing the campus, the university is guided by its Campus Plan, which stresses the creation of spaces that promote physical activity, enable social connections, improve health and wellbeing, foster sustainability and ensure accessibility.

Jeff Nulty, landscape architect with UBC Building Operations, notes that the approach to campus design has adapted to changing priorities over the years. “With a greater appreciation for and understanding of sustainability and biodiversity, planting design and landscape maintenance practices are evolving,” he says. “The campus landscape was once imagined as mass plantings of single non-native plant species and lush weed-free lawns, but today, UBC gardeners are focused on accommodating change, rather than trying to preserve a static aesthetic.”

“I identify as having First Nations ancestry, so I feel pride in taking part in this project. It feels really cool to be doing something regarding my heritage.”

Today, campus landscapes reflect more informality and a broader plant selection, and are aesthetically appealing while also playing a role in addressing environmental concerns related to irrigation, biodiversity, maintenance resources and resiliency.

For Ewert, working in the Library Garden has personal resonance, she says: “I identify as having First Nations ancestry, so I feel pride in taking part in this project. It feels really cool to be doing something regarding my heritage.”

Ewert is part of a long tradition of university gardeners. UBC has, for years, been recognized for its landscaping—most recently topping the Times Higher Education World University Ranking’s list of 10 most beautiful universities in Canada. UBC’s landscape architect Dean Gregory points out that the campus environment has always played an important role in the university’s commitment to wellness and sustainability.

“The site of the university itself was selected to be a place that would be supportive to learning,” Gregory notes. “That was 100 years ago, and today, student wellbeing is at the forefront of what we do. The public realm plays an enormous role in helping to reduce stress, providing environments in which learning can happen outside, and creating a memorable experience for people while they are here.”

Jenniffer Sheel, superintendent of municipal and construction services, points to a 2014 SEEDS research project that asked students where they felt most happy. Of the top 10 places cited by students in the Map Your Happiness Ripple Lab, four were public realm spaces that included the Rose Garden, Martha Piper Plaza, Main Mall and Nitobe Garden.

“These are spaces that are really good for mental and physical wellbeing,” says Sheel, whose portfolio includes the soft landscape team, waste management team, the labour group, garage and construction office. “The campus is really about connecting to nature and to each other. There’s no purchase necessary to be outside.”

Courtesy of UBC.

Courtesy of UBC.

— This story was a guest post by UBC writer Jessica Werb. Click here to go to the original story.