The City of Vancouver will pay the E-Comm 911 call centre $24 million this year to provide dispatch services for police and fire departments.

Last year, the total tab was $22.3 million.

In 2020, it was $22 million.

The city also contributes to a regional fund via the Metro Vancouver agency that pays for the call-taking portion of 911 ambulance calls, which get transferred to B.C. Emergency Health Services.

The regional fund totalled $4.2 million in 2020.

In the last month, the question of whether the city is getting good value for its investment was raised at a Vancouver Police Board meeting and at city hall, where Coun. Sarah Kirby-Yung successfully moved a motion to have city staff assess “the E-Comm situation.”

The situation, as Kirby-Yung spelled it out in her motion, involves an understaffed agency unable to handle call volumes — particularly non-emergency calls — to the satisfaction of the public, the service’s biggest union and even E-Comm’s president, Oliver Gruter-Andrew.

Those factors coupled with the city’s police and fire departments, along with the Ministry of Health-funded ambulance service, saying they are also understaffed has made for unprecedented pressures on public health and safety in Vancouver.

“There hasn’t been a clear or transparent discussion around this service, and what value we’re getting from it,” Kirby-Yung said by telephone this week. “So I think it’s really important for council to be briefed on our entire public safety ecosystem.”

Added Kirby-Yung. “We spend time discussing the Vancouver Fire Rescue Services’ budget, we spend time discussing the VPD budget. There has been little to zero dialogue with respect to E-Comm.”

'Register my displeasure'

Discussion about E-Comm’s value to Vancouver has been amplified and exposed by the pandemic, the ongoing overdose death crisis and climate change-fuelled tragedy, including last summer’s heat dome.

In one case, Vancouver firefighters say they waited 11 hours for an ambulance crew to arrive and transport an elderly person suffering heat exhaustion to hospital. The BC Coroners Service reported 99 heat-related deaths in Vancouver between June 25 and July 1.

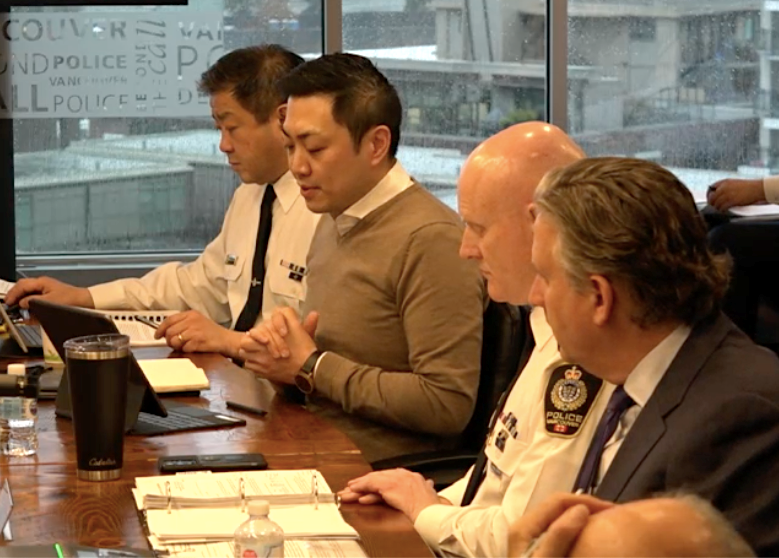

Police board member Frank Chong, who has supported the VPD’s request for more officers and participated in discussions about residents’ dissatisfaction when trying to report crime, aired his concerns about E-Comm at a public meeting last month.

“I'd like to register my displeasure today publicly with regards to E-Comm, and hopefully we can have further conversation in-camera with regards to what is happening, and further discuss how the VPD can engage with E-Comm at this point,” said Chong, whose remarks were followed by a response from Police Chief Adam Palmer.

“Thank you for your comments,” Palmer said. “They are well-pointed, and we have the same concerns with E-Comm.”

Palmer said one of his deputy chiefs, Howard Chow, is in discussions with E-Comm. At the same time, he added, the VPD’s concerns are not unique to Vancouver, with the issue a topic with the B.C. Association of Chiefs of Police.

Long wait times on non-emergency line

Chong’s comments came after the police board discussed a case where a citizen complained about waiting two hours on a non-emergency line to report a man lighting a fire on a sidewalk near Broadway and Collingwood.

He never got connected to an operator.

The next day the citizen, whose name was redacted in his written complaint, made a second attempt to report the incident and got the same disappointing result.

The incident occurred Sept. 7, 2021 when the citizen said he approached the man about lighting the fire. The man then pointed a “hand torch” in the citizen’s face before lunging at him. The citizen pushed him back and left the scene.

The citizen didn’t think the incident warranted a 911 call. He said he tried to report the crime online but discovered that because violence was involved, it couldn’t be reported.

“I'm very concerned that there seems currently to be no effective way for citizens to report non‐emergency criminal activity to the city or to the VPD,” the citizen wrote.

“I recognize that the incident in question was relatively minor but documenting and tracking such low‐priority incidents must surely be valuable for developing crime prevention strategies and citizens surely should not have to wait for 911 emergency situations in order to report crimes.”

The police department report in response to the citizen’s complaint pointed to E-Comm’s “operational staff shortages, which have affected their ability to meet their target goals” as the reason for the complainant’s inability to file a report.

“In this particular incident, it appears that the complainant unfortunately called during a time when there were lower staffing levels,” said the report authored by Sgt. Mehrban Sidhu.

On hold for two hours, or longer

In 2021, the average wait time for non-emergency calls was approximately six minutes but callers regularly experienced lengthy delays, often on hold for two hours or longer, Sidhu said in her report.

An explanation for those delays can be found in an 11 per cent increase in 911 calls in Vancouver from September 2020 to September 2021. That spike has meant non-emergency call-takers having to be reassigned to handle the volume of 911 calls.

Vancouver police receive, on average, more than 600 calls for service every day.

E-Comm prioritizes the calls and assigns them to officers based on each call’s risk to public safety. Most citizens are not aware that when they contact 911 and the VPD’s non-emergency line, they are actually reaching E-Comm.

Calls that are medical in nature get transferred to B.C. Emergency Health Services, which Sidhu pointed out is also experiencing a shortage of call-takers.

Prior to November 2021, 911 call-takers had to stay on the line with a caller requiring paramedics.

In November, E-Comm and B.C. Emergency Health Services management implemented a temporary procedure allowing 911 medical calls to be forwarded to BCEHS’s automated system, thereby freeing up 911 call-takers sooner.

That shift in policy has reduced the time a person waits on the phone when calling 911, according to E-Comm president Oliver Gruter-Andrew. Whether it has reduced response times from ambulance dispatchers is a question he referred to B.C. Emergency Health Services.

“Our average speed to answer is back to being below five seconds,” he said. “Historically, it's been in sort of a one-second average range. We're aiming for below five seconds, and we're back to below five seconds.”

'It's not what we want to see'

It’s the non-emergency call wait times that consume Gruter-Andrew.

“We're trying to solve what it will take to fix that problem because we all recognize waiting on the phone for an hour with all those delays, and the COVID implications, and the heat dome stuff — everything together — it’s not what we want to see,” he said, acknowledging criticisms about “our ability to answer non-emergency calls is absolutely valid.”

But, he added, the issue of long wait times is one he and his staff highlighted with police chiefs and departments going back to 2019. Since then, E-Comm has conducted a review of its services and commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers to produce a report on the service.

“We’re in the stages right now to work in detail about what came out of the reports, how do we take that forward, how do we make it affordable, how do we make it workable for the public, for police officers, for fire departments and, very importantly, for E-Comm’s people,” he said, noting the strain on employees.

“Ultimately, the answer to me — unless calls stop coming in — is we need more people.”

Asked what he would say to a citizen frustrated by long wait times, he said:

“I feel bad — it's not what it should be. We are well aware of the issue and the underlying causes. It's been a topic of discussion between us and our funders for a number of years now. We are working with our funders in partnership to resolve this because it affects everybody.”

'Avoid going to the bathroom'

Donald Grant, president of Canadian Union of Public Employees Local 8911, represents about 550 call-takers, 911 operators and dispatchers connected to 33 police agencies and 40 fire departments.

Grant spoke to council last month about his concerns with E-Comm and pointed to the PricewaterhouseCoopers report, which showed the need for more staff.

“It confirmed what we knew, but to a tune of a number that we didn't expect,” he said.

“To meet current targets, the report called for the immediate addition of 125 full time call-takers to meet the emergency and non-emergency demands being placed on our organization.”

In an email, Grant said the E-Comm shared service makes sense but is so understaffed that 911 operators regularly do shifts without breaks “and even monitor their water intake to avoid going to the bathroom so they can take just one more call.”

He applauded council for the increase this year to the E-Comm budget but said the service is struggling and needs to be “right-sized.”

“These are the same struggles Vancouver would be facing if it operated the service alone, but then the costs would be Vancouver's alone to carry,” said Grant, a trained dispatcher for Vancouver and other fire departments.

“It will take a concerted effort to make sure E-Comm has enough staff and resources to deliver the service the people who live in British Columbia deserve.”

Vancouver city staff, meanwhile, are expected to present a report to council based on Kirby-Yung's motion by April.

@Howellings