Edwin Yobani Zarabia, who is wanted in Texas for a murder dating back 19 years ago, lives in a tent in Oppenheimer Park. Photo by Mike Howell

Edwin Yobani Zarabia, who is wanted in Texas for a murder dating back 19 years ago, lives in a tent in Oppenheimer Park. Photo by Mike Howell

The man sitting at a picnic table in Oppenheimer Park is sipping coffee from a paper cup and smoking a cigarette as he talks about what his 41-year-old life has become.

His name is Edwin Yobani Zarabia.

He just spent another night in a tent in the park, where he’s lived for several months and become part of a growing homeless community of campers.

"It’s not really good, but it’s not really bad,” said Zarabia of his life in Oppenheimer.

The sun has come up, his girlfriend is still asleep and some of his neighbours are standing outside a charity’s kitchen window on Dunlevy Avenue to get free coffee and food.

City crews are removing garbage from the encampment, park rangers are making their rounds and police officers are on hand to keep the peace.

Squawking seagulls seem to be everywhere.

The encampment, which has been at the centre of a political and community debate for months, recently passed its one-year anniversary mark.

The dozens of tents and campers observed by the Courier last Wednesday confirm it continues to thrive, despite efforts from the city, province and others who found housing this summer for more than 100 people.

But Zarabia’s stay here is somewhat immaterial to his story of coming to Canada, which is shrouded in mystery and high drama involving several countries, immigration officials and law enforcement.

Documents from the Immigration and Refugee Board, Canada Border Services Agency, the San Antonio Police Department, along with photographs and excerpts of medical records, provide a captivating narrative of Zarabia’s journey.

What stands out most is this: He is wanted for the murder of a woman in Texas that occurred 19 years ago, with the San Antonio Police Department confirming this week that the warrant is still active.

Zarabia, who has repeatedly told authorities he is from Colombia and denies his involvement in the murder, said police are looking for the wrong man, and that he was never in San Antonio.

He also denied he was deported from Texas in 1999 to Mexico after being convicted of a trespassing charge — a key link police have relied on in the murder case.

“That’s not true, that’s wrong,” he said, speaking softly in English, his words coloured by a thick Spanish accent. “I was never deported from the United States to Mexico. They said, ‘You killed the person Lilita.’ I told them, ‘Why I have to come from far away to kill somebody? You really think I crazy, or what you think about?’ I don’t know this person. I don’t know what peoples talking about. I’m not the killer.”

‘Ligature strangulation’

The body of Lilita Easter Moke, 47, was found March 7, 2000 behind a bar in the basement of what police described as a mansion on West Lynwood Avenue in San Antonio.

Tenants discovered Moke lying face up and in “an advanced state of decomposition,” according to the arrest warrant issued June 10, 2000.

The mansion in San Antonio where the body of Lilita Moke was discovered in March 2000. Photo Google Maps

The mansion in San Antonio where the body of Lilita Moke was discovered in March 2000. Photo Google Maps

“It was discovered by investigating officers that [Moke’s] arms were bound behind her with some type of cord,” the warrant said. “The cord was also tied around her neck.”

A pathologist with the Bexar County Forensic Science Center ruled the cause of death “ligature strangulation.”

Zarabia’s name, however, is not on the warrant. Police identified Antonio Diaz Lisenber as the suspect, which Canadian documents allege was one of four aliases used by Zarabia.

Police believe Zarabia and Lisenber are the same man because fingerprints taken from Lisenber in 1999 related to a criminal trespassing charge in Texas match the fingerprints Zarabia provided to Canadian authorities.

Furthermore, a resident of the West Lynwood Avenue house — Marco Alanis — positively identified Lisenber in a photograph. Alanis, whose family owned the property, told police Lisenber lived at the house and worked as a gardener, but vanished March 1, 2000.

Four poorly scanned copies of photographs included in the documents appear to be Zarabia, although he only identified one when shown by the Courier, and believed it was taken in Canada.

Another key piece in the case against Zarabia is “hairs microscopically matching [Moke’s] were found on the clothing and bed sheets of [Lisenber]” at the house, the warrant said.

Moke, who was a seniors’ caregiver at the time of her death, didn’t live at the West Lynwood Avenue mansion, which is located in a leafy neighbourhood with expansive homes and boulevards similar to Shaughnessy. She resided a few blocks away at her family’s home and often walked to a grocery store on a main road in the area called San Pedro Avenue.

“When she would see gardeners working on yards, [she] would always say something or yell at them,” the warrant said. “[Moke] did not like the noise that was made by lawnmowers.”

A lawnmower was on the front lawn of the West Lynwood Avenue house on the day Lisenber vanished, but the lawn had not been mowed, according to Alanis’s statement to police.

Man without a country

Why Zarabia has not been returned to Texas to face a murder charge is complicated.

But it is based on the Canadian government’s decision not to extradite him, and an Immigration and Refugee Board ruling in 2016 that concluded Zarabia is likely not the killer.

Though Zarabia has told authorities he is from Colombia, the Colombian government has no records of him and found the birth certificate he provided upon entry to Canada in 2003 to be bogus.

The Mexican government also has no records of Zarabia, a short, sturdy man with deep set brown eyes, wide nose, a mess of thick black hair and a noticeable scar on his forehead.

Fingerprint searches done via Interpol in Panama, Ecuador, Guatemala, Venezuela, Belize, Brazil, Chile, Guyana, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Honduras also came up negative.

And with no immigration status in the United States, the Canadian Minister of Public Safety refuses to deport Zarabia to Texas to face the murder charge.

He is, effectively, a man without a country.

“This creates an unresolvable dilemma for Mr. Zarabia,” wrote Immigration and Refugee Board panel member Leanne King in her May 2016 decision to release Zarabia from jail.

Zarabia had been in custody from 2014 to 2016, having been arrested after Canadian authorities learned of the Texas murder warrant.

Prior to his arrest, he said, he worked at two IHOP restaurants — one in Vancouver, the other in Richmond — and lived in an apartment in New Westminster.

In 2006, three years after he entered Canada at Fort Erie, Ont. and claimed refugee status, Canada’s refugee protection division declared Zarabia a convention refugee.

He was on his way to becoming a permanent resident when Canada Border Services Agency agents arrested him at gunpoint outside an IHOP in Richmond.

The Canadian government, represented by the Minister of Public Safety’s office, requested Zarabia remain in custody after his arrest because his nationality was unknown.

In addition, his refugee status had been revoked — not because of the Texas warrant, but because of two criminal convictions in 2004 while in Ontario.

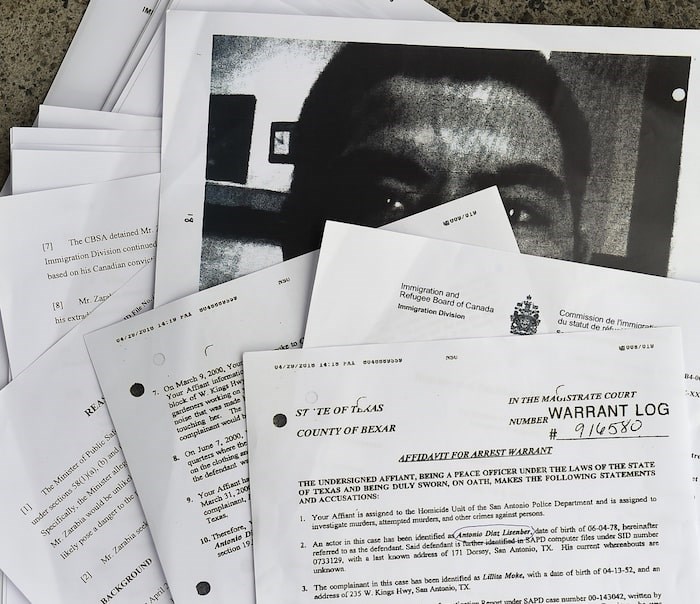

Some of the documents obtained by the Courier regarding the case of Edwin Yobani Zarabia (a.k.a. Antonio Diaz Lisenber). Photo Dan Toulgoet

Some of the documents obtained by the Courier regarding the case of Edwin Yobani Zarabia (a.k.a. Antonio Diaz Lisenber). Photo Dan Toulgoet

One was for assault, the other assault with a weapon, although the “minimal sentences he received indicate the offences involved a very minor level of violence,” King wrote.

Those convictions and the murder warrant were main arguments the government put forward to keep Zarabia in custody. The government also argued Zarabia would go underground, if and when authorities determined his nationality and he had to be deported.

‘Not satisfied’ Zarabia is murderer

King disputed much of the Canadian government’s evidence — and the lack of it — in her ruling. She pointed out that a warrant issued does not necessarily mean the person named has committed the crime.

“I am not satisfied that Mr. Zarabia is likely the person who committed the murder in Texas,” she said.

On the criminal trespassing charge in Texas in 1999:

“It is clear from the evidence that Mr. Zarabia was in San Antonio, Texas in October through December 1999, and was convicted of criminal trespass. This, however, is the only reliable evidence before me connecting Mr. Zarabia to any event in the U.S. Mr. Zarabia denies this event and does not believe he was there.”

King goes on to say that medical evidence of physical and psychological trauma Zarabia experienced since 1999 “indicates there are likely medical reasons he cannot remember this event.”

On the photograph that tenant Marco Alanis saw to identify Lisenber:

“There is no explanation about what picture was identified, or where it came from. Had it been in the possession of the police detective, or was it in the possession of Alanis? Without an explanation about what photograph was identified by the witness Alanis, and where that photograph came from, there is no credible or trustworthy evidence upon which I can conclude that Mr. Zarabia was the person identified by the witness.”

On the hair that microscopically matched the victim’s found in the room where Alanis said Lisenber was staying:

“This is not forensic evidence linking Mr. Zarabia to the victim, this is witness evidence based on a photograph and the allegations of the witness Alanis about where someone who the police identified as Lisenber had been living a week earlier.”

Added King: “There is no information that any forensic evidence from Mr. Zarabia [a.k.a. Lisenber] such as his fingerprints, or his hair was found at the crime scene.”

Zarabia described King as a person with “good spirit” for releasing him, but said the consequences of his arrest have left him in despair.

“Since I was arrested,” he said, “my beautiful life I tried to make… everything is going down now. Look at me now. I’ve never had to sleep in a park like this.”

Colombian drug cartel

The documents obtained by the Courier show Zarabia has experienced trauma, lives with mental illness and suffers from memory loss, as alluded to by King in her explanation of why he couldn’t remember the trespassing charge in 1999.

The story he tells — some of it corroborated in documents, some of it not — is that he has suffered greatly since his family was killed by a Colombian drug cartel when he was eight years old.

He said his father refused to the sell the family’s property to the cartel, so they burned down the family home with the family inside; Zarabia was the only one to escape.

He claims to be from a tribe in the jungles of Colombia and was able to travel through Central America after he joined the cartel — not by choice, but by necessity to stay alive.

His job was to deliver “samples” of cocaine to potential customers, never getting caught because of his age and his smarts, he said, noting his work took him eventually to Mexico.

As he got older, he wanted to separate himself from the cartel and crossed the border illegally into the United States. He mentioned staying in a small town in Texas, but denied he was ever in San Antonio, which is 240 kilometres from the Mexican border.

“People told me not to go there because it was too close to the border,” he said about his worry of being deported.

Asked why it is then that a resident of the mansion identified him as a gardener at the West Lynwood Avenue property, Zarabia replied: “I want to know.”

He was equally challenged to explain why police linked him to the homicide.

“This is a very good question. I have the same question myself.”

While in the United States, he said, he worked in a restaurant in Chicago, before moving to Miami. There, he said, he met a pastor at a church.

He told the pastor about his past and what happened to his family. A few days later, he returned to the church to meet with the pastor, only to be taken at gunpoint from what he believes were cartel members.

He said they took him to a highrise building, placed a hood over his head and threw him from a fifth-floor balcony. It was punishment, he said, for deserting the cartel.

He said he broke multiple bones in his body, suffered a skull fracture and was in Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami for several months, before ending up in New York for surgery.

A transcript of an Immigration and Refugee Board hearing in 2015 noted Zarabia’s lawyer at the time attempted to obtain copies in 2010 of his client’s hospital stay in Miami.

But, the lawyer said, the records were destroyed.

Medical records referred to in King’s ruling note that Zarabia was in Bellevue Hospital in New York in 2001 “following a fall from a fifth-floor balcony.”

A medical assessment report done four years later in Vancouver pointed out Zarabia told U.S. doctors the fall had been an accident.

The tent city in Oppenheimer Park hit the one-year mark this month. Photo Dan Toulgoet

The tent city in Oppenheimer Park hit the one-year mark this month. Photo Dan Toulgoet

“Now, in 2005, he was telling doctors [in Vancouver] he was pushed,” the assessment said. “He also reported that Colombian drug dealers had been looking for him and trying to kill him in both the U.S. and Canada, and had been seen three times in Canada.”

The doctors questioned whether Zarabia was experiencing paranoid delusions. They prescribed Prozac, Ativan, Olanzapine and Trazadone. He was also given morphine for his chronic pain.

The documents show Zarabia has been diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress, a severe personality disorder and major depression.

A Canadian psychiatrist wrote: “The information available to us paints a picture of a man who has experienced profound physical and psychological trauma beginning in childhood. It is our sense that Mr. Zarabia has lived a marginal existence whilst in Canada. He appears to have been homeless much of the time, often living in graveyards.”

‘I’m not guilty of anything’

It was in New York, Zarabia said, that he met a Canadian doctor who recommended he seek refugee status in Canada. Records show he crossed the border in April 2003 at Fort Erie, Ont.

The documents indicate he spent a couple of years in Ontario before heading west to Vancouver. By 2009, Zarabia appeared to be settling in to a more stable life, as a psychiatrist from the New Westminster Mental Health Centre wrote in a report.

The psychiatrist noted Zarabia met regularly with his primary therapist and psychiatrist, and that he kept appointments and took his medications.

“His mental status and functional abilities have greatly improved since the start of treatment in November 2008,” the psychiatrist said.

“He demonstrates insight into his difficulties and has been very proactive with respect to a variety of issues and rehabilitation services. He is currently working part-time and enrolled in a computer course this summer, which will also assist him with literacy challenges.

“He has made good use of community resources. He has successfully maintained safe housing. In summary, we believe Mr. Zarabia has made significant progress, and demonstrated a high level of responsibility in his recovery.”

That same year, he was attending weekly therapy sessions at the Vancouver Association for Survivors of Torture. A letter from the organization stated, “Mr. Zarabia had made tremendous progress in his healing process and had ceased to self-harm.”

That was 10 years ago.

He now lives in a tent, doesn’t have a work permit or a job, and survives on close to $600 per month in welfare.

It was the arrest in 2014, he repeated, that sent him in a downward spiral. He wants to sue the United States government for changing the trajectory of his life.

“The United States has to know that I’m in this life, that I’m here,” he said, motioning with his hands at the tents all around him. “I have no business with the United States. Never I have business. I have nothing to hide. Inside me, I feel free. I’m not guilty of anything. So if the United States wants to destroy me more than what they did, go ahead. I don’t really care. I have nothing to lose.”

‘A beautiful person’

Jose Alfonsin has lived for almost 20 years wanting justice for his older sister, Lilita.

Though he understands the position of Canadian authorities, and learned from the Courier of Zarabia’s mental state and living conditions, Alfonsin wants Zarabia returned to Texas to stand trial.

“It’s disheartening that the Canadian immigration [panel member] did not retain him for longer in order for the U.S Department of Justice and the San Antonio Police Department to do their work,” he told the Courier by telephone Monday.

“It’s been unfortunate. We pray that the proper officials hopefully one day see it worthy for him to be extradited and face the charge.”

Alfonsin said he was concerned that a fugitive was free in Vancouver and worried that another innocent person could become a victim, although he acknowledged a person is innocent until proven guilty.

“The evidence that [police] found at the time, everything points to him,” he said.

He described his sister, who was single and had no children, as a lover of life, who liked to dance and travel. She was a certified nurse’s aide and once worked in the hotel industry in Chicago, St. Louis and San Antonio.

“She was a beautiful person, but very independent and preferred her space,” he said. “She really did not have a social circle.”

Alfonsin said he learned of his sister’s murder while watching television on a night his family was hosting a political fundraiser for a state representative.

Lilita wasn’t reported missing at the time, but the description of the woman given on the breaking news report suggested it might be Lilita, who is a half-sister to Alfonsin. He was familiar with the home on West Lynwood Avenue, noting it belonged to a doctor and his wife.

“They had described my sister — what she wore, and everything,” he said, noting he immediately called the medical examiner’s office. “They called me the next day to say it was in fact her, based on dental records. They couldn’t identify the body, otherwise.”

Alfonsin mentioned Det. John Kellogg a few times when he spoke to the Courier, noting he was the lead investigator at the time of his sister’s murder. The Courier reached Kellogg by telephone Monday. He is now a patrol sergeant with the San Antonio Police Department.

“The Alfonsins — they lost their sister, so they have a hole in their family,” he said. “And that hole is never going to be filled back in, knowing that the guy is somewhere where everyone knows he’s at, and nothing has happened.”

Added Kellogg: “That just makes that hole get bigger until something happens to fill in the pain. And I don’t think that pain is going to be filled, even when he’s picked up and brought to justice — should that happen — they’re still going to be hurt.”

‘I die so many times’

When Zarabia was released from immigration custody three years ago, the documents indicated his lawyer would help him find “suitable housing.”

Zarabia said he ended up in a single-room-occupancy hotel on Granville Street, but only stayed briefly because of “illegal activity” happening with some of the tenants.

He sought refuge in Stanley Park, where he lived for several months. He spent time on the streets in other parts of the city until he set up a tent at Oppenheimer.

At one point, he said, he secured housing at the Flint Hotel on Powell Street until a man shot him with a bb gun. He didn’t bother to fight back and returned to Oppenheimer, where he said people generally leave him alone.

He is confident he could find a job, but doesn’t want to work illegally, he said, fearing he could get arrested and put in jail again. Without status or a work permit, he said, he can’t better his life.

He printed his full name — Edwin Yobani Zarabia — in a reporter’s notebook to emphasize he’s not lying about his real name. He also produced a photocopy of personal ID, with his photo.

A condition of his release is that he reports monthly to the Canada Border Services Agency, which he said he has done for three years. In the meantime, immigration officials continue their search to determine Zarabia’s nationality.

He’s has told them he is willing to return to Colombia, or any other country that will take him — if he can’t get his refugee status back in Canada.

The Canada Border Services Agency refused to discuss his case.

The waiting has taken its toll on Zarabia, who confided through tears that he has considered buying enough fentanyl to kill himself. At the same time, he added, he tries to stay strong.

“I go for a walk with my girlfriend,” he said of how he fills his days. “We go to different shelters, find some clothes. Go to laundry. I go see my doctor, take my medication. Sometimes, I go to library. My girlfriend try to teach me a little bit computer. Try to keep busy.”

Does he have hope?

“I have it, but it’s not enough. It’s only a spiritual hope I have. So it looks like I come from the dark to the light. Back and forth. I die so many times, then I come back. From the dark to the light. So I continue this way.”