A team of Canadian researchers was planning to use their new infrared camera to help find animals in the arctic, and it worked.

It worked better than expected.

They had been expecting to spot seals, walruses and polar bears out on the ice, but when they looked at their images, they spotted something else: Narwhals.

UBC PhD student Katie Florko, who was part of the team and is the lead author of a just-published study, says spotting narwhals was expected, but not to the degree they did since infrared cameras don't penetrate water well.

"Narwhals only surface briefly, so we expected it would be challenging to accurately detect and count narwhals using infrared during our aerial surveys," she says in a press release.

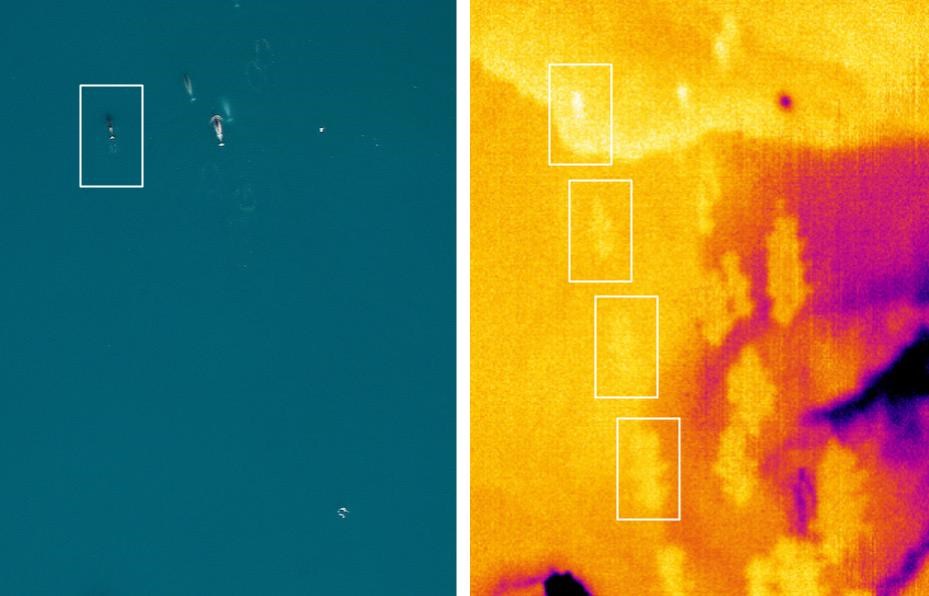

What they did find, though, was something else. They're called 'flukeprints.'

As a narwhal passes through the cold ocean it disturbs it, causing the water, which is different temperatures at different levels, to swirl around. The infrared camera was able to pick up these disturbances (the flukeprints), which are like short-term footprints, in the images.

"We thought we’d only see the little bit of their back that appears when they surface,” Florko explains. "In hindsight, it’s totally logical that you’d see the flukeprints when you have temperature-stratified water. This has been seen with bigger whales, but it never crossed my mind.

"I was shocked, excited, confused, and a bit embarrassed that I hadn’t thought of it before.”

The flukeprints are bigger than the medium-sized whales, as well. It allows researchers to more easily detect narwhals and figure out which way they're headed.

"The creativity in science is really highlighted here,” Florko says. “There are a lot of tools available to researchers that can be used in ways that they might not initially consider but give them surprising results.”