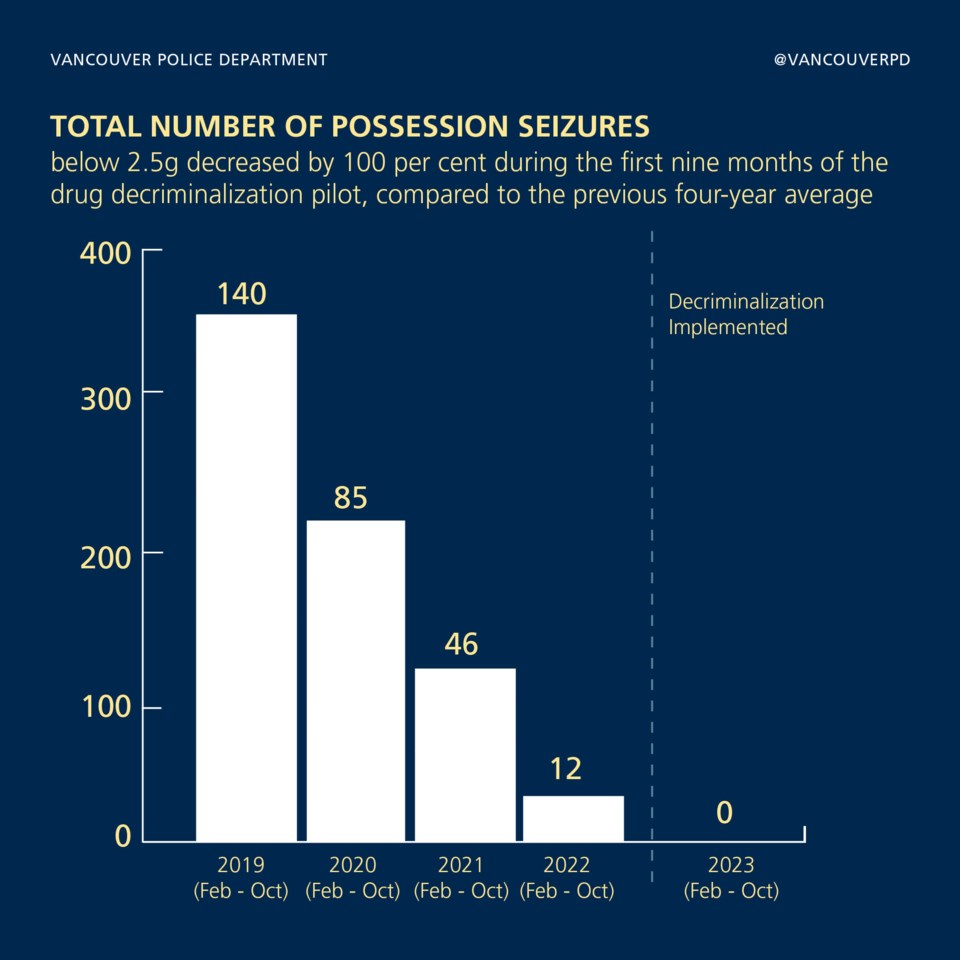

The Vancouver Police Department released data Tuesday that they say shows “a dramatic drop-off” in small drug seizures in the city after B.C.’s decriminalization trial began Jan. 31, 2023.

In a news release, the VPD said officers did not make any drug possession seizures below 2.5 grams during the first nine months of the trial. In addition, all drug possession seizures, regardless of weight, decreased 76 per cent during the first nine months of the trial, compared to the previous four-year average.

“We support a caring and compassionate approach to solving the toxic drug crisis,” said Insp. Phil Heard, who oversees the VPD’s drug unit.

“We don’t support putting people in jail simply because they use drugs or struggle with substance-use disorder. We believe that the decriminalization pilot is an important part of a larger strategy that is required to respond to the ongoing crisis.”

2.5 grams of fentanyl

Under the trial, which was approved via a Health Canada exemption, people in possession of 2.5 grams or less of fentanyl, heroin, morphine, crack and powder cocaine, methamphetamine or MDMA cannot be arrested or have their drugs seized.

Heard clarified at a news conference Tuesday that such a quantity of drugs would be seized if a person had committed a crime such as a break-in to a vehicle. But if that person was later released from custody, the drugs would be returned to the person as their personal property.

Heard said the year-old law, which applies to people 18 and older, was not a “massive shift” for a department that has typically not arrested people for simple possession of drugs, unless connected to a crime.

He added that “health diversion” is now part of the law.

“For people that aren't familiar with the drug laws, it probably seems like a wholesale change,” he told reporters at the VPD’s Cambie Street precinct. “But I think it was a much smaller change than people perhaps realized.”

Decrease in public complaints

The new law continues to be controversial but Heard said decriminalization has not led to an increase in complaints about public drug use from residents.

“We've actually seen a decrease in public complaints around public consumption,” he said. “But that doesn't mean that circumstances don't arise where people rightfully have concerns around public drug use, and we're still responsive to that.”

The Health Canada exemption for the decriminalization trial contains exceptions that limit drug possession on the grounds of elementary schools, high schools and licensed child-care facilities.

In addition, drugs cannot be readily accessible to the driver of a motor vehicle or watercraft. Drugs cannot be consumed within 15 metres of any public outdoor play structure at a playground, spray pool or wading pool or skate park.

The law is the result of a successful push from former Vancouver mayor Kennedy Stewart and the B.C. government to have Health Canada grant the province an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

The exemption expires Jan. 31, 2026.

The B.C. government is on record saying decriminalization is a critical step in the fight against the toxic drug crisis, which killed more than 14,000 people between April 2016 and January 2024.

Heard acknowledged that decriminalization has not decreased the number of overdose deaths, which continue to be driven by fentanyl — one of the drugs allowed under the 2.5 gram threshold.

“We haven't seen any statistical changes in those variables since decriminalization took effect,” he said.

'Such reports are patently false'

Heard took time during the news conference to criticize an article posted last month on a website that said minor drug seizures by VPD increased after decriminalization came into effect in January 2023.

Heard didn’t name the website, but an article posted Feb. 14 on The Maple said seizures of drugs at or below the 2.5 gram threshold increased by 34 per cent, according to documents the non-profit site obtained via a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act request.

“I am aware of reports claiming that VPD drug seizures have actually increased since decriminalization took effect,” he said. “Let me be clear: such reports are patently false, and are wholly incorrect.”

Heard said the VPD provided the recipient of the data a covering memorandum that explicitly highlighted nine different limitations. One of the key limitations listed, he said, was that the total quantity held by the individual was not reflected in this dataset.

“In reality, the average seizure involves more than six different items or rows in the spreadsheet,” he said. “Review of VPD data confirm that all seizures following decriminalization coming into effect were fully compliant with the Health Canada exemption.”

'We need more transparency'

The Canadian Drug Policy Coalition said Tuesday in an emailed statement that while the VPD’s data is positive, it does not offer a complete picture of the “criminal-legal realities” for people who use drugs.

“We need more transparency,” the coalition said. “Ultimately, for decriminalization to effectively reduce harm we must focus on reducing overall police involvement and interactions. Any outreach and referral related to substance use should be the purview of health and social systems — not police.”

The coalition said police not making simple possession seizures does not mean there are no police interactions with drug users — “and we know that interactions with police and criminal justice systems drive harm for people who use drugs.”

The coalition argued the public does not know the extent to which police may categorize seizures under “possession for the purposes of trafficking” instead of simple possession.

“Further, there are huge gaps in the data we can't access: how do we measure police interactions that would not be deemed seizures, but function similarly and have similar impacts?” the coalition said.

“Informal and undocumented interactions with police can mimic the harms under criminal law, but are not tracked.”

The coalition said there are clear links between drug criminalization and harm. Enforcement has not decreased drug availability or use, is extremely expensive and is clearly linked to an increased risk of overdose and cycles of homelessness.

“Decriminalization reduces incarceration, police involvement, stigma, and disconnection from services — all of which drive harm and overdose,” the coalition said.

“This is why decriminalization is an important piece of a necessary broader shift in drug law and policy that must include equitable access to overdose prevention sites, health care, responsibly regulated substances, affordable housing, adequate income and evidence-based, voluntary treatment."

More than 1,110 officers trained

As of January 2024, more than 1,110 VPD officers had completed online courses to familiarize themselves with the Health Canada exemption.

All new recruits and experienced officers are now required to complete training when they are hired, according to the VPD, which said support of the trial is in line with the department’s “track record of progressive drug policy, which focuses enforcement efforts on violent criminals and organized crime groups that produce and traffic the harmful street drugs that are fuelling the drug toxicity crisis.”

The department pointed to its support for the Insite supervised drug injection site on East Hastings Street when it opened in 2003. The VPD also noted it became the first Canadian police force to stop routinely attending overdose calls, in recognition that automatic police attendance could be a barrier to people calling 911.

“VPD has also been a leading advocate for the safe supply of substances to combat the harms associated with the toxic illicit drug supply, and believes that harm reduction strategies, when combined with prevention, education and appropriate enforcement, can reduce the number of lives lost due to illicit drug toxicity,” the release said.

Note: This story has been updated since first posted to add comments Heard made at a news conference. A statement from the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition was also added to the story.