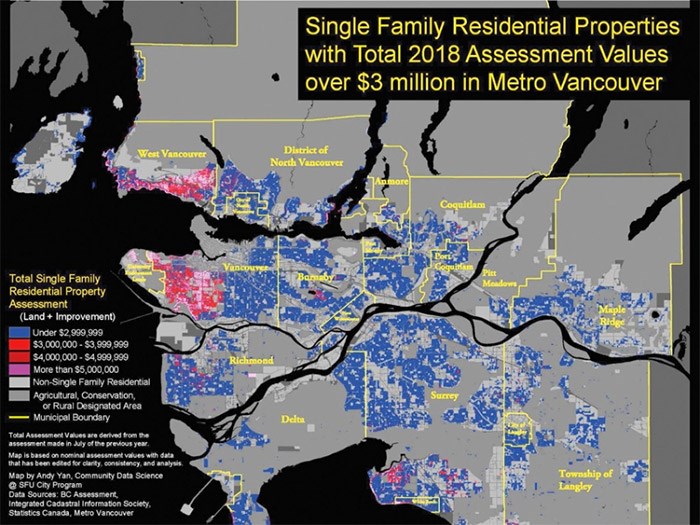

This map shows the distribution of multi-million-dollar properties across Metro Vancouver. image supplied, Andy Yan, SFU City Program

This map shows the distribution of multi-million-dollar properties across Metro Vancouver. image supplied, Andy Yan, SFU City Program

Statistics that point out a higher than average percentage of high-end homes owned by non-residents in West Vancouver and prices that are far out of proportion to declared local incomes point to some of the key issues facing the municipality, according to Simon Fraser University researcher Andy Yan.

Compounding the issues, West Vancouver also has the second-highest percentage of homes worth more than $3 million in the region and the most skewed ratio of house values to local incomes, says Yan, director of SFU’s City Program.

Those factors combine to make the affluent North Shore community a special case when it comes to policies on everything from taxing wealth to attempting to limit global capital from warping the housing market.

Of West Vancouver’s 16,334 residential properties, 6.2 per cent are owned by non-residents, according to the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corp., which released those statistics in December. Only Vancouver and Richmond have a higher percentage, at 7.6 and 7.5 per cent respectively.

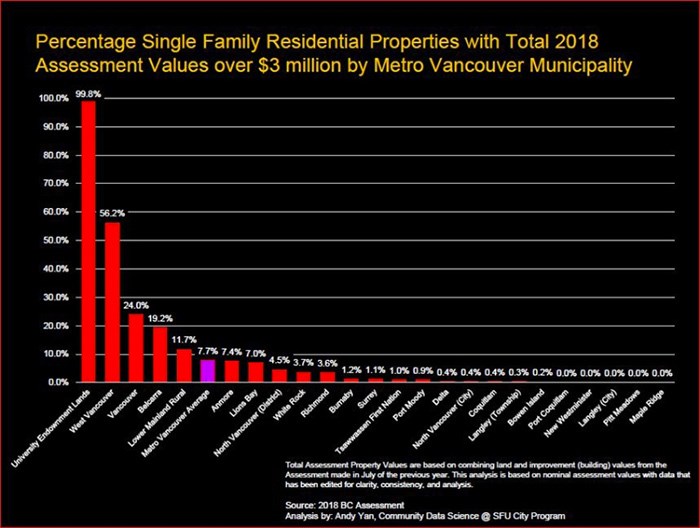

But West Vancouver also has the second-highest number of homes – 6,760 – worth more than $3 million, which also accounts for the second-highest percentage of homes – 56 per cent – worth that much in the region, second only to the University Endowment Lands, according to Yan’s analysis.

That percentage of multimillion-dollar mansions compares to 24 per cent of homes in Vancouver, 4.5 per cent in the District of North Vancouver and less than half a per cent in the City of North Vancouver, according to Yan.

Source: graphic supplied Andy Yan, SFU City Program

Source: graphic supplied Andy Yan, SFU City Program

Even more significantly, says Yan, the ratio of median household income to median house price is seriously skewed in West Vancouver, where house prices are about 25 times the annual household income.

Across the Lower Mainland as a whole, house prices are about 11 times household income, while they hover at about five times nationwide.

A house price that’s between three and five times household income is generally accepted as healthy, says Yan – a far cry from what’s happening in West Vancouver.

“You’re the outlier of the outliers,” says Yan. “Housing to income is so out of whack. It’s in its own world compared to the rest of the country.”

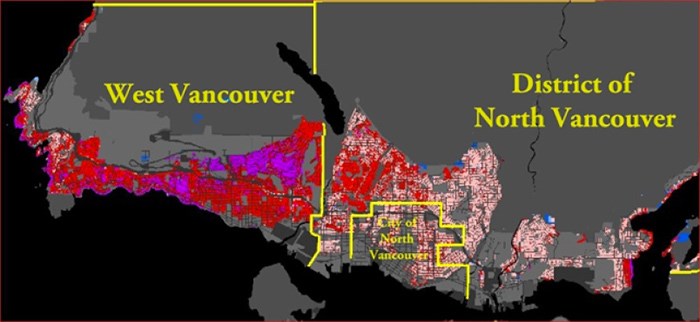

Detail of map showing multi-million dollar properties across the North Shore. Homes in red are worth over $3 million. Dark red properties are worth over $4 million. Areas in purple have homes worth over $5 million. image supplied, Andy Yan, SFU City Program

Detail of map showing multi-million dollar properties across the North Shore. Homes in red are worth over $3 million. Dark red properties are worth over $4 million. Areas in purple have homes worth over $5 million. image supplied, Andy Yan, SFU City Program

Statistics on property owned or being bought by non-resident, or foreign buyers, is more difficult to track.

Although official statistics point to only 6.5 per cent of property in West Vancouver owned by non-residents, real estate analysts note that information is notoriously difficult to track due to widespread use of trusts, corporations and proxies to stand in for beneficial owners and skirt tax regulations.

Foreign buyers accounted for 24 per cent of real estate sales in West Vancouver in the months prior to the 15 per cent foreign buyers’ tax being imposed in August 2016. Foreign buyers also spent more than Canadians – forking over an average of $4 million per property transaction during that time compared to $2.8 million for Canadians.

Since then, the number of real estate sales involving non-residents has dramatically decreased. According to official statistics released by the ministry of finance, in most months last year, there were fewer than five foreign-buyer transactions in both North and West Vancouver. Last March and December accounted for the highest number of foreign-buyer transactions in West Vancouver that were officially reported to government, accounting for about one out of 10 residential sales.

Those figures would not include non-resident transactions done through corporations or using other legal loopholes, however.

The NDP government has vowed to collect more complete information on property transactions in the future to track beneficial owners.

Yan said it’s not just one set of statistics that impacts the community, but the way they have an effect on each other and “how it all compounds” when it comes to housing.

“It’s this idea that small numbers have big effects,” he said. “How does that ripple out to the rest of the municipality? You have these very complex discussions that are going to have to happen.”