Under new City proposals, new development heights in Chinatown would be restricted, in response to concerns from residents over the pace of change in the area. Photo Chris Cheung

Under new City proposals, new development heights in Chinatown would be restricted, in response to concerns from residents over the pace of change in the area. Photo Chris Cheung

At a Council meeting last Thursday (June 28th), city staff presented their final report and recommendation on Chinatown’s zoning amendments to mayor and council.

Over 70 speakers were on the agenda to speak, and by far the most common thread was how Chinatown needs more housing. Many people spoke about the need for seniors housing, market rate and subsidized rental housing.

Why is it so hard to build appropriate housing in Vancouver? Especially in a neighbourhood with vacant buildings and empty lots?

Well, two new studies, by the C.D. Howe Institute, and UBC Sauder School of Business, and a 2017 article from the Fraser Institute show that Vancouver’s fees, restrictive zoning and lengthy permit application processing times are the highest in Canada.

According to the Fraser Institute, City fees add $78,000 per unit built, with an increase in the works. Building permits take on average 21 months, during which time the owner needs to carry the cost of the property, often with no rental income, but an obligation to keep paying city property taxes. And these costs, of course, are born by the end user or renter.

Compare this with an average 7 month wait and $16,000 in fees in Burnaby.

So, how’s this relevant to Chinatown specifically, then? It seems like there’s been ample time to address housing, regardless of the time and cost. And in fact, there have been 6 new buildings built in Chinatown, since 2012, two of which are rental.

The holdup at this point is a new proposed downzoning of Chinatown that has seen new housing projects put on hold. The downzoning proposes to remove 60% of the housing stock out of Chinatown.

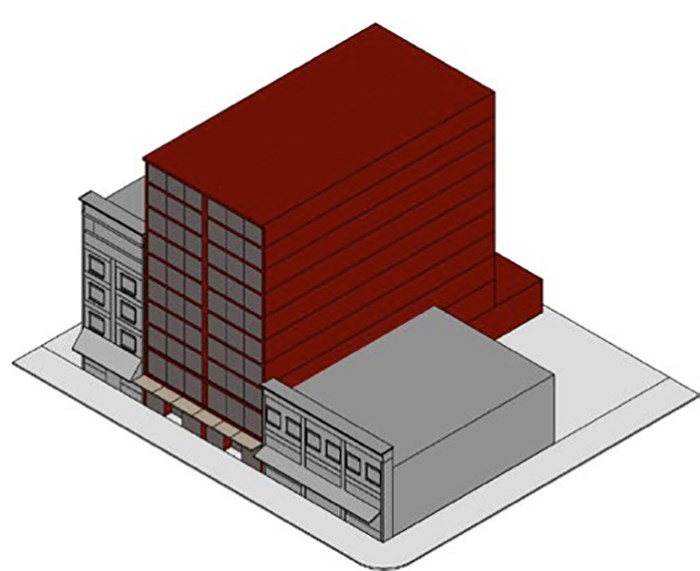

City staff say the downzoning is necessary to maintain traditional building height and character. And, in a couple of examples in the planning department’s presentation, they showed the impact on new vs old zoning on a sample new building.

Photo supplied

Photo supplied

On a 50’ wide lot, this represents about 6250 ft2 of commercial ground floor space, and about 52,000 ft2 of residential. 58250 total square feet.

It’s important to note that this doesn’t actually reflect any of the new buildings that have been built, it’s kind of a worst-case scenario used to illustrate what may be currently allowed.

A couple of things stand out for me – this is a 10 story building, and at 90 feet, each floor would be actually less than the standard 8’. I don’t think this building could even be built in the current building codes. Also, there’s no allowance shown for services on the roof, or for minimum retail ceiling height, which would cut into rest of the floors. The two similar buildings that have been built are actually only 8 stories, not 10. This design would never be approved, so someone is fudging here.

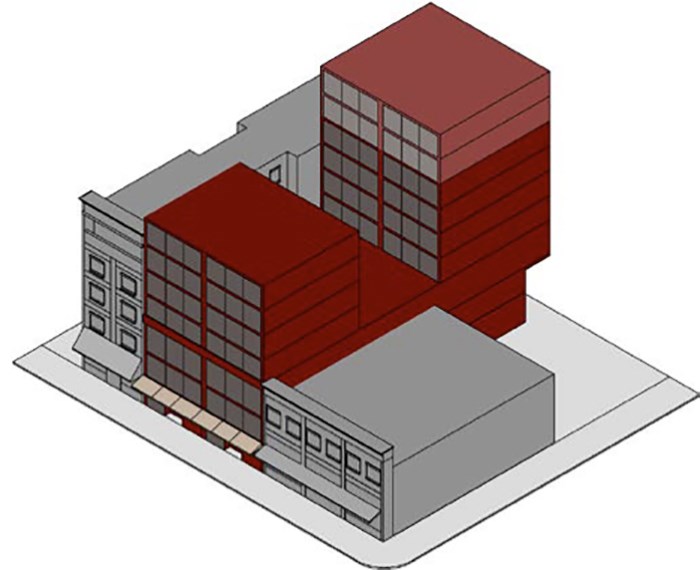

Okay, so now onto the new zoning.

Photo supplied

Photo supplied

So much nicer, right? That interior courtyard is cool, and would allow a lot more natural light, right? And the height of the building on the street is only 7 stories, not 10, so much lower and more in keeping with the surrounding buildings.

Wait, why are the top two stories at the back lighter? That’s because the last two stories are “conditional.” Conditional on what? They don’t really say.

But part of the new zoning is that community consultation is required.

If recent community consultation is any indication, anyone from anywhere can show up to a meeting and influence planning decisions. So you might as well cut those back two stories off.

So how much space are we talking about here? About 11,400 ft2 of commercial space (ground floor retail and second floor office). 17960 ft2 of residential. 29,360 total.

So the total square footage is down by 50%. Spreading the fixed costs over 50% less buildable space will add to the total cost of each unit. How much is hard to quantify, but assume $8 million for land, $1million for demo and site prep, $400,000 for design, engineering, and development fees (irrespective of community contributions). Assume 20 units, and the total cost increase amounts to $235,000 per unit.That’s in addition to increased construction cost (more exterior walls), and increased operating costs (less energy efficient design).

The bigger issue, of course is that the total housing, in addition to being more expensive to build, is reduced by a whopping 65%.

So the new zoning allows for residential development, but much less of it. And at a much greater cost. I know which building I’d rather live in, but I’d never be able to afford it.

City staff did a great job building a case for reduced zoning in Chinatown, but only by fudging their examples and hiding the single biggest issue facing Vancouverites. If we are going to solve our housing crisis, city staff are going to have to start taking it seriously.

–

Andrew Samuel has been a partner in a small Chinatown business since 2010, and is passionate about heritage, livability and coconut buns