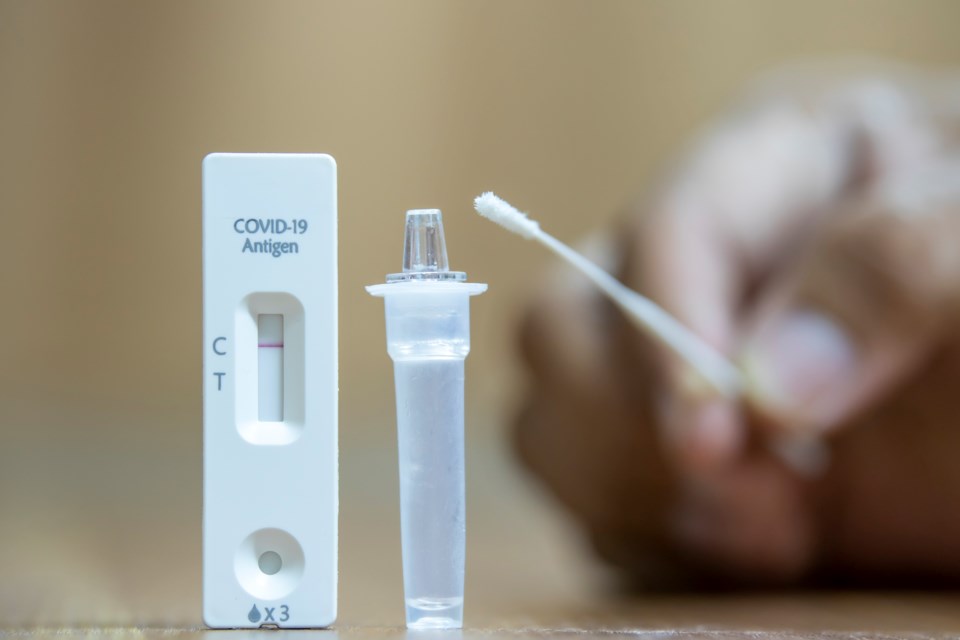

It was a sad day last week to have to send funds to another province to buy a rapid antigen test to enhance my safety and the safety of those around me.

It was a sad day, mainly, because my province’s health and political authorities have chosen not to provide what is freely available many other places, and I cannot understand how a province that has been so smug at times about its handling of the coronavirus has fumbled the ball so far into the game.

But it was a sad day, also, because I am among the millions of British Columbians who have abided every restriction, every guideline and every adaptation in the last 21 months, only to find there was a limit from authorities on the commitment to my safety.

On the eve of our second pandemic-infested holiday season, with the Omicron variant rewriting the script and spreading more virulently worldwide than anything we’ve seen, these authorities have failed to honour the covenant with the public to provide every available resource to moderate harm and risk.

Along this exhausting journey, few have questioned whatever it has cost, and most everyone has argued for whatever it has taken to pursue the only objective: to make us as safe as possible each day as COVID morphed and defied. The assumption was that even modest measures to mitigate would be applied without hesitation.

Yet there is no accelerated schedule for booster shots for the twice-vaccinated, as there is elsewhere, and the mass-produced self-administered antigen tests are only going to arrive in the province long after the holidays, long after they could have helped us curtail what experts expect will be a serious spike in cases. Instead, as announced Friday, a new wave of restrictions instead of a new wave of relief.

This is reminiscent of the federal delays a year ago in procuring vaccine when other countries were jabbing and the excruciatingly slow start of the provincial rollout, except that in this case the country has procured and the province has demurred. The supply into B.C. has targeted long-term care facilities and places where there are outbreaks, but the general public has been left out of the plan for the time being. Less than 10% of the supply has been used.

The test is by no means perfect. In the pandemic, after all, what so far has been? We are getting by with good enough. In an ideal world, we’d be able to take regular polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, which have more accurate results.

But the antigen tests are excellent at identifying infectious people, whether they are vaccinated or not. While it seems counterintuitive, people are most infectious before they display symptoms, which is why their routine use when you aren’t feeling bad is so valuable.

But beyond the antigen test’s sheer scientific attributes is a social science of psychological comforting, particularly at this sociable time of year, in that they help us understand when we are not threatening infection to others.

It doesn’t prevent transmission, of course, and it is no substitute for a vaccine. And after watching the manufacturer’s tutorial video, the test itself when it arrives is going to require a careful process that approaches a 15-minute version of the delicate creation of a great meal.

But practice ought to make pretty much OK, and where it is used widely it serves as a guardrail to encourage those with positive test results to isolate and to get a PCR test to confirm the finding. They’re best employed shortly ahead of an activity.

It is, as Health Canada puts it, “an extra layer of defence.” Yet our provincial health authorities have strangely downplayed their importance at this important time. Their explanations have seemed peevish: difficult packaging, a better test is soon available, too difficult to self-administer, yada yada, even though other jurisdictions are self-testing away. If we are living in a world of good enough, then the tests at hand need to be applied, not hoarded, even if it means pulling in the professionals to perform them.

The problem for our provincial health officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry, and Health Minister Adrian Dix is that they are for once lagging behind their federal counterparts and most infectious disease experts.

One such expert I follow, Dr. Victor Leung of Vancouver, notes the tests are there to protect, to enable, to stay (as in the classroom in an outbreak), to treat and to empower. Meanwhile, Dr. Theresa Tam, the federal health officer, is warning that Canada is about one week behind the Omicron hot mess of the United Kingdom and advocates the greater use of rapid antigen tests (OK, let’s finally call them RATs) in the overall fight.

It has taken public patience to withstand what have been conflicting, shifting directions in the iterative science of how to contend with coronavirus. But the public has largely held up its end of the bargain and followed the guidance, in large part because it has trusted authorities to have their backs.

In an era of anti-vaxx and anti-mask protests, it’s a strange phenomenon to witness the circulation of a fast-growing Free The RAT petition for access to no-cost self-tests – people demanding even more measures to make them safer. This is a certain signal to Henry and Dix that, far from anger about a heavy hand, there is an emerging cohort upset with the unusually light touch at this moment.

Granted, we have found the marathon of the pandemic to be an ultra and Omicron has caught governments flat-footed, but an underlying principle is that trust in authority is what separates us from chaos. We may never learn who decided this was the time to keep one of the tools tucked in the toolbox. The province’s rationale for its reticent use and short-selling of the tests – followed by an assurance that they’re coming, they’re coming – has the peculiar flavour of a deflection from a mistake that won’t be politically admitted.

I smell a rat, even if I can’t yet use one.

Kirk LaPointe is publisher and editor-in-chief of BIV and vice-president, editorial, of Glacier Media.