An SFU transportation expert says the North Shore is getting short-changed by the province and TransLink – and that region should be next in line for rapid transit.

UBC LRT (Photo supplied)

UBC LRT (Photo supplied)

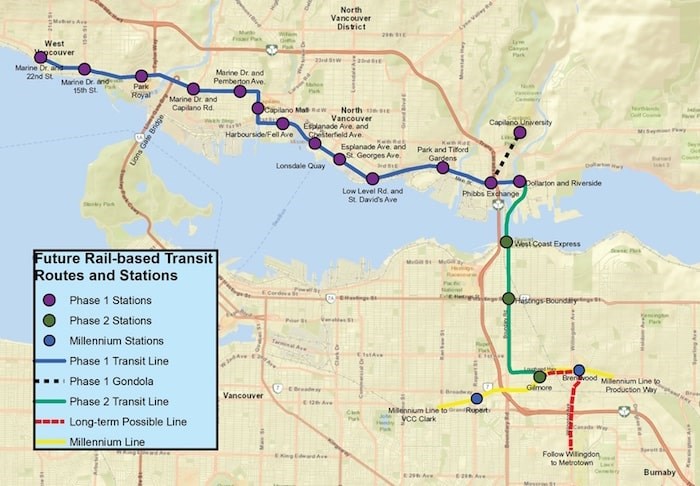

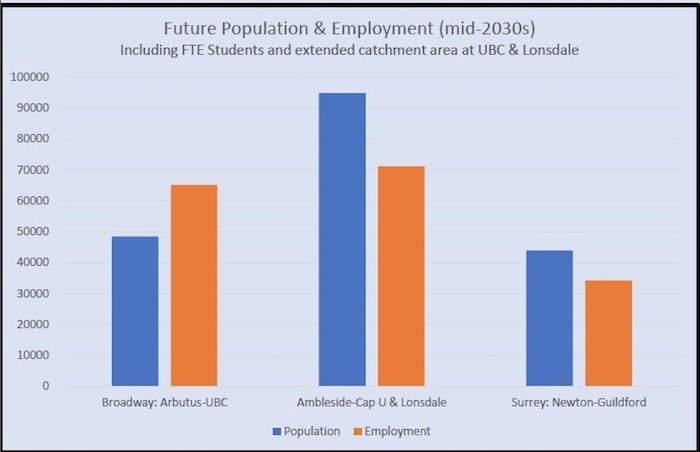

Stephan Nieweler, doctoral researcher and transportation instructor in SFU’s department of geography, and two former students have released preliminary findings from a study that concludes adding a fixed-rail link across the North Shore and, eventually, plugging it into the SkyTrain system across Burrard Inlet would result in more people choosing to get out of their cars and onto transit than either the Surrey-Newton-Guildford line soon to start construction or the contemplated Broadway subway line from Arbutus to UBC.

The study started as course work by two of Nieweler’s fourth-year urban transportation students, Gabriel Lord and Chris Humphries. But their professor was so impressed with their work, he encouraged them to continue on under his guidance. Together, the three used census data, official community plans and interviews with the North Vancouver Chamber of Commerce and major employers to make the case for North Shore light rapid transit.

“Anecdotally, it appeared the situation was really deteriorating on the North Shore yet the plans said there should be a subway to UBC. We were scratching our heads here,” Nieweler said. “My concern as part of the bigger picture is the North Shore is never going to see anything happen, probably for a couple decades if we go ahead with all of these massive projects that are planned for Surrey and Broadway. There’s only a limited pool of money for rapid transit.”

After a lengthy study, Simon Fraser University transportation expert Stephan Nieweler is calling for a fixed rail LRT line for the North Shore. photo Mike Wakefield, North Shore News

After a lengthy study, Simon Fraser University transportation expert Stephan Nieweler is calling for a fixed rail LRT line for the North Shore. photo Mike Wakefield, North Shore News

Trains, trucks and gondolas

Nieweler is pitching a light rail line from Dundarave to Phibbs Exchange that travels along Marine Drive jutting south at Capilano Mall, down to the CN Rail corridor through Harbourside, on to Lower Lonsdale and then east via either Low Level Road or Third Street to Phibbs. Nieweler envisions a gondola based at Phibbs taking students, staff and visitors up to Capilano University. A second phase of the project would join the light rail line to the Maplewood area, which is under consideration for rezoning into a major jobs and residential centre, over a new Second Narrows bridge designed to accommodate freight rail, LRT and truck traffic, before connecting to the Boundary Road corridor with stops at the West Coast Express and eventually Gilmore or Brentwood SkyTrain stations. A third light rail line would run the length of Lonsdale from the Upper Levels Highway to the SeaBus terminal.

A new B-line bus is scheduled to start making the same 11.5-kilometre Dundarave-Phibbs run starting next year, one of the transit improvements coming to the North Shore as part of the Mayors’ Council 10-year vision. TransLink estimates the trip will take 40 minutes. Nieweler says that’s not good enough.

“At 40 minutes, are you really going to get massive uptake? In my opinion, no. You need to get that down to the low 20s,” he said. “(It’s) an OK first step but they’re saying that’s going to be enough for the foreseeable future. What I’m saying here, based on the data, it’s not. And the congestion we see at the bridges is only going to get worse.”

Nieweler estimates it would take 30 minutes for commuters to get from the SkyTrain in Burnaby to Dundarave using his proposed line. That could coax a lot of North Shore employees out of their cars and off the bridgeheads, he said.

As for possible highway expansions like the Lower Lynn Improvement Project, the benefits are always short lived, Nieweler added.

“That band aid they’re doing by Mountain Highway maybe that gives you a few years. But we need rail rapid transit,” he said.

Us and them

Nieweler based his analysis on the work of American transportation expert Robert Cervero who studied 23 light and heavy rail systems across North America. He separated out the top 25 per cent based on ridership and studied how many people live and/or work within 400 metres – or a five-minute walk – of a station. Cervero concluded a range of 14 to 30 residents/jobs per acre was needed to justify the expense for light rail and 27-45 to justify metro lines like a subway or SkyTrain.

The population and employment density of the Main-Marine corridor today ranges from 14 at the sparest points to almost 60. The Lonsdale corridor itself has 74.9 per acre.

“Those are big numbers,” Nieweler said. “I mean, that’s Toronto subway density.”

In raw numbers, Nieweler’s analysis found the North Shore LRT, if it existed today, would have more than 111,000 people and employees within 400 metres of the line, compared to 93,500 on the proposed Arbutus to UBC line or 46,680 for Surrey LRT.

They also forecast into the future, using the Official Community Plans to gauge population and employment growth. Over the next 20 years, the case is even stronger, Nieweler found, with almost 160,000 residents or jobs within 400 metres of the North Shore line, compared to 113,500 for the Broadway extension and 78,100 in Surrey.

“Why is the North Shore excluded when, in theory here, it looks like it would be a really, really good generator of the new trips?” Nieweler asked. “The key thing is here, we have the densities right now that justify light rail, if not more than light rail on the North Shore.”

Based on the average cost per kilometer of LRT lines in Canada, Nieweler estimates the North Shore portion of his LRT proposal could be built for $600 million to $1.1 billion compared to $3.5 billion ballparked for the UBC proposal.

UBC and the North Shore also differ in that the North Shore suffers from daily traffic congestion while students and faculty at UBC are already much more likely to be taking transit because of the U-Pass program, Nieweler said.

“When I worked at TransLink, we had this mantra called performance-based investment. It’s basically this idea that public funds should be dedicated to projects that have the biggest impact rather than just the political aspect,” he said. “We could do something on the North Shore at a much lower cost that would have a much bigger impact.”

Not so fast

Nieweler presented his preliminary findings to the Integrated North Shore Transportation Planning Project team when it was compiling ideas and research over the last year, but when the INSTPP report and recommendations were released last month, several components of Nieweler’s plan were outright rejected.

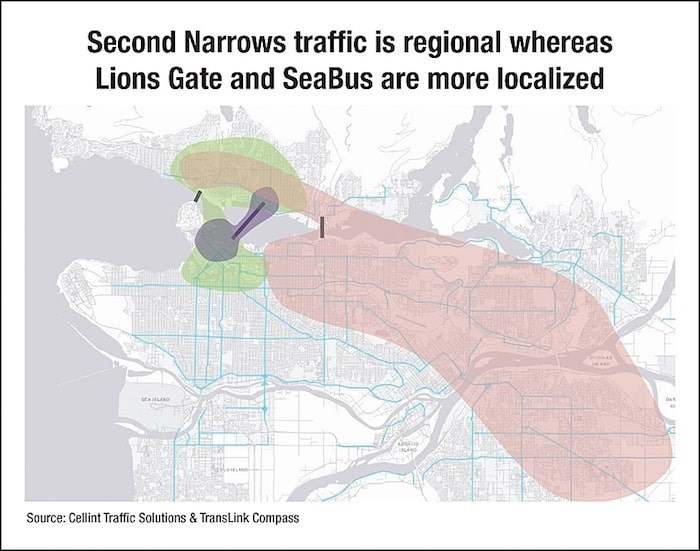

A gondola would not decrease travel time between Phibbs and Capilano University enough to justify the costs, it found. CN has no plans at all to replace its rail bride over the Second Narrows. And while the report did recommend further investigation into a Lonsdale-downtown rail tunnel, the commuters who currently drive over the clogged Ironworkers every day tend to originate in areas too far from the existing SkyTrain lines to make a North Shore connection an appealing alternative. Nieweler questions those conclusions but North Vancouver-Lonsdale NDP MLA Bowinn Ma, herself a transportation engineer, said she stands by them.

The North Shore will very likely be getting a new express bus connecting Phibbs to the SkyTrain as a result of INSTPP’s work, Ma said, and the Main-Marine B-Line could be seen as a precursor to eventual rapid transit.

Geoff Cross, TransLink’s vice-president of transportation planning, expressed similar sentiment.

“I think the conclusion that we need better transit connections east-west and north-south is the right one. I wouldn’t jump to the exact technology, alignment and stations yet. There’s a lot of work that needs to be done to make sure that we’ve got the right priorities set,” he said.

When it comes to Nieweler’s methodology, Cross said there is more to consider than jobs and population densities. TransLink also studies things like car ownership rates, population demographics, employment types and current commuting patterns.

“He doesn’t have all the tools to look at what would drive ridership,” Cross said. “I think he’s kind of jumping the gun on that.”

At the very least, TransLink should commit to conducting the same type of study it did when determining the business cases for the Surrey and Vancouver megaprojects, Nieweler argues.

Barring any changes in the way TransLink, the mayors and the province select which projects get approved, Ma said, the North Shore LRT would have to go through the same process as the current Mayors’ Council plan.

“The 10-year vision is a consensus plan agreed to by 22 different local governments. This is an incredible feat if you really think about it. A lot of hard work went into those negotiations to reach the conclusions that they did,” she said.

TransLink is kicking off its next major regional transportation plan next year.

“They’ll be looking at all potential corridors that may warrant high-capacity transit over the next 30 years,” Ma said. “Because of the work of INSTPP, I expect to see some kind of North Shore connection to the Burrard Peninsula to be looked at very, very carefully.”

That timeline is exactly what Nieweler is worried about.

“Unfortunately, I feel the congestion on the North Shore is going to get much worse over the next decade and at this rate, we’re not going to see a significant solution for 20 years maybe,” he said. “I don’t think the North Shore can wait that long. I think it’s going to be a crisis situation with the traffic if we wait that long.”