On the same day new provincial data showed most drug-related deaths occur in private residences, local health agencies announced a research project that works toward combatting that very phenomenon.

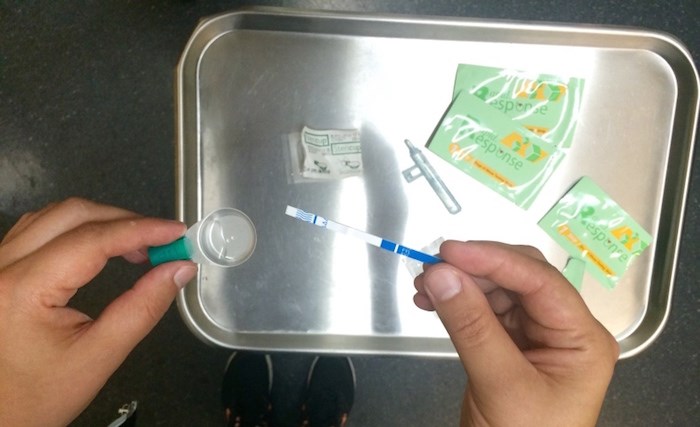

New home-drug testing kits determine whether drugs are contaminated with fentanyl or a fentanyl-analogue, ideally encouraging users with drugs that test positive to take more caution and not use alone. Photo Vancouver Coastal Health

New home-drug testing kits determine whether drugs are contaminated with fentanyl or a fentanyl-analogue, ideally encouraging users with drugs that test positive to take more caution and not use alone. Photo Vancouver Coastal Health

On May 15, Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) and the B.C. Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) announced a pilot project that provides take-home testing kits to people who use drugs. The kits determine whether drugs are contaminated with fentanyl or a fentanyl-analogue, which produces a similar response to fentanyl, ideally encouraging users with drugs that test positive to take more caution and not use alone.

Drug testing is already administered by trained technicians at Coastal Health sites in Vancouver, but researchers want to see whether users can successfully test for drugs on their own.

“We see signals that people do want this information, that they do change their behaviour… when they have that information,” said Dr. Mark Lysyshyn, a medical health officer at VCH. “We believe [the drug-testing kits] will prevent overdoses.”

According to the new B.C. coroner’s report, fentanyl or its analogue was a factor in approximately 85 per cent of all overdose deaths in the province in the first quarter of 2019. The latest provincial statistics also revealed that nearly nine out of 10 drug-related deaths in the first three months of this year occurred indoors, mostly in private residences. Lysyshyn believes the majority of those deaths happened because users were alone and could not be revived with naloxone, a synthetic drug that can reverse an overdose. No deaths were recorded at any supervised-consumption or overdose-prevention sites, according to the coroner’s report.

Each take-home kit contains five free drug-testing strips. To test for fentanyl-contamination, people mix a small amount of the drug in a few drops of water and then insert the strip, which should indicate whether fentanyl or an analogue is present within seconds, similar to a home pregnancy test. The kits can be picked up at Insite, the Molson Overdose Prevention Site, the Overdose Prevention Society and the St. Paul’s Hospital overdose prevention site, as well as seven different locations throughout the Southern Interior of the province.

While Lysyshyn believes the kits could save lives, he acknowledged the drug-testing strips have significant limitations. They only test for fentanyl or fentanyl-analogues, not other dangerous substances that show up in Vancouver-area opioids, such as benzo analogues which can knock out users for hours at a time. They also don’t indicate how much fentanyl may be present in the drug. Nor are the test-strips always successful in detecting traces of carfentanil, a tranquillizer typically used to sedate large animals. Carfentanil has experienced a recent resurgence in the local opioid market, according to this week’s coroner’s report.

“It does cross-react with carfentanil, but it's less sensitive to carfentanil than it is to fentanyl,” Lysyshyn said. “The other problem is because carfentanil is so potent, when it's present in street drugs it's present in a very low amount. So, we are seeing situations where the strip will be negative, but then later we'll find out that carfentanil was present.”

Since most regular opioid users already expect what they’re buying to contain fentanyl — Lysyshyn said 90 per cent of all opioids they checked tested positive — the take-home drug-testing strips might prove most valuable to people who use other drugs, according to Lysyshyn.

“We see much lower levels of contamination in some other drug types like stimulants or ecstasy,” he said. “So, the strips may actually be more useful in those situations where the person is not expecting, not desiring to take an opioid — and it could be devastating if they took fentanyl because they're not tolerant and they're not prepared.”

The new coroner’s report also details what many on the frontlines of the overdose crisis have long known. Males are dying much more often than women in overdoses where fentanyl or an analogue was nearly always present.

There was one bright spot among the report’s findings. In the first three months of this year, drug-related deaths in British Columbia were down about 32 per cent from the same time last year. Between January and the end of March, 268 British Columbians died from fatal overdoses. In 2018, that number was 395.

However, Leslie McBain, co-founder of Moms Stop the Harm, a Canada-wide network of parents who have lost their children to drug-related deaths and advocate for stronger government action on the overdose crisis, said she’s not necessarily encouraged by the latest figures.

“Statistically, it looks significant, but let's wait three more months and see what happens,” said McBain, who lost her only child, Jordan, to an opioid overdose in 2014. “I'm just thinking it might be a blip.”

Speaking to the Globe and Mail earlier this week, BCCDC researcher Michael Irvine said different harm reduction measures, including overdose-prevention sites, take-home naloxone and opioid replacement therapy, could explain why the province saw a decline in drug-related deaths earlier this year.

Rather than take-home drug-testing kits or the recent decline in overdose deaths, what brings McBain the most hope is the federal government’s decision this week to expand injectable opioid-replacement treatment and add diacetylmorphine (heroin) to its List of Drugs for an Urgent Public Health Need, two moves that bring the government closer to a policy of safe supply.

Both McBain and Lysyhyn agree safe supply is the only solution to the overdose crisis, while Lysyshyn said measures such as drug-testing strips are mere “Band-Aids.”

“Everybody in the know knows that that is the bottom line. That is the only way we're going to stop the overdose crisis,” McBain said. “Everything else we do, whether it's test strips, safe consumption sites, naloxone — nothing is going to stop it until we have safe supply. Period.”

@benjaminmussett/ [email protected]

See related video: