SFU scientist Chris Mull studies a common thresher shark (Alopias vulpinus) in southern California during a west coast juvenile thresher survey.

SFU scientist Chris Mull studies a common thresher shark (Alopias vulpinus) in southern California during a west coast juvenile thresher survey.

The dead sharks found days apart on a beach in Delta might be part of a “nursery” of sixgill sharks living off the Vancouver coast, says a local shark researcher.

Unlike humans, when a sixgill shark is born, it needs no help from mom or dad, says Chris Mull, a post-doctoral scientist at SFU. “The mothers will pup and leave…. Because [shark pups] are miniature versions of adults, they don’t need parental care.”

Shark pups don’t lactate like mammals or get food from their parents like birds. But they do need protection from predators until they get a bit bigger and can fend for themselves.

“The Howe Sound and Strait of Georgia may serve as a nursery,” Mull says. “Most of the sixgill sharks here are less than a metre to two and a half metres and once they get longer they move offshore.”

A sixgill shark can reach six metres in length and survive 2,500 metres under the surface.

Mull looked at the photos of the two shark carcasses found on different days in Delta.

“I think they are both sixgill sharks,” he says. “Unfortunately these photos don't show characteristics which could be used to easily identify them including the dorsal fin, pectoral fins, which are decomposed here, and the teeth.”

This shark carcass found on Centennial Beach in South Delta might be a juvenile sixgill that is part of a population of sharks spending their youth in Howe Sound and Strait of Georgia. Photo Tami Ryder

This shark carcass found on Centennial Beach in South Delta might be a juvenile sixgill that is part of a population of sharks spending their youth in Howe Sound and Strait of Georgia. Photo Tami Ryder

Although the person who found one of the carcasses speculated that it was a thresher, Mull says “I would be more confident that this is a sixgill shark, based on the carcasses, how common they are in the region, and the fact that two washed up in such close proximity within a short time.”

While common thresher sharks can be found in B.C., this is the northern extreme of their range and they are uncommon or rare here, he says.

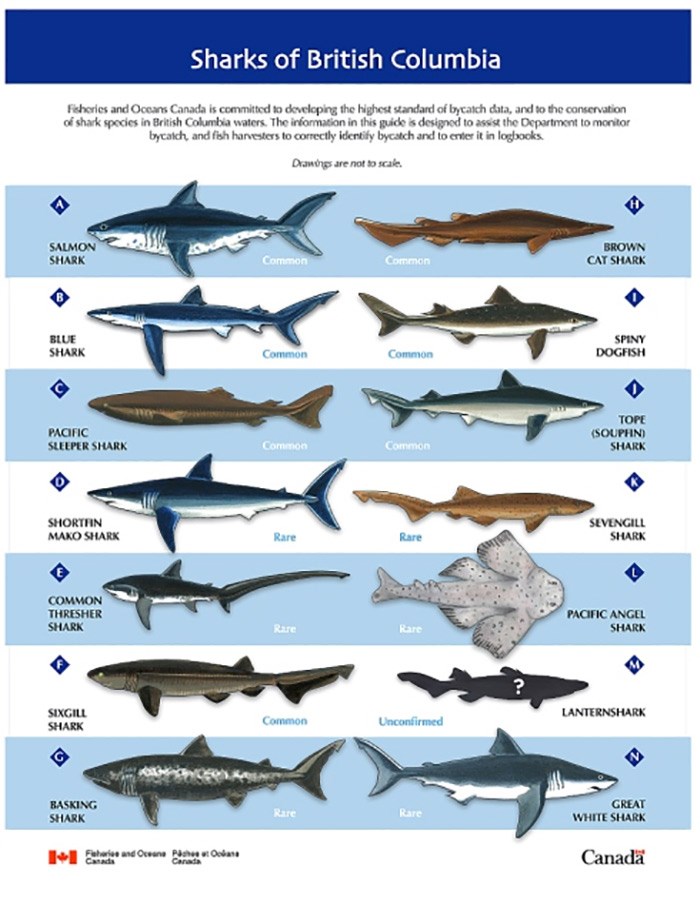

The appearance of two sharks in Delta seems to have caught most people by surprise. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans says 14 types of sharks are known to frequent B.C. waters but some of them, including the great white, are rare.

This shouldn’t make us afraid to go for a swim in the ocean, says Mull, who never grew out of a fascination with sharks and stingrays that began when he was a child growing up in Hermosa Beach, Calif.

“People should have absolutely no concern about being bitten by a shark in B.C. waters,” he says. Not only has there never been a recorded attack but sixgills are “pretty slow moving and docile” and they’re “not particularly interested in humans.”

“Humans aren’t dinner for any sharks,” he adds. “We’re not part of their natural ecosystem….. Sharks have much more to fear from humans.”

From the turn of the 20th Century to the 1950s there was a small commercial shark fishery in the Puget Sound. Sixgills and basking sharks have large livers that are filled with lipids and fats, an attribute that helps them maintain buoyancy but also created a demand for their liver oils. But that demand didn’t last long and the fishery closed. In the 1990s there was a small recreational fishery, Mull says, but it too was shut down, this time because there was not enough information about whether the fishery was sustainable.

Basking sharks were once common off the shores of British Columbia. Now they are endangered here. Photo Wikicommons

Basking sharks were once common off the shores of British Columbia. Now they are endangered here. Photo Wikicommons

People tend to have an irrational fear of sharks including, it appears, U.S. President Donald Trump who reportedly told Stormy Daniels “I hope all of the sharks die.”

It’s not just the movie Jaws that did sharks a disservice. Mull says that “people tend to fear what they don’t understand,” which is why he’s hoping his ongoing research lets people know how much we will lose if certain shark populations continue to be endangered. Basking sharks, which were once abundant in BC waters, are on that list.

Chris Mull holds up a finetooth shark in Bulls Bay, South Carolina. “We were sampling as part of an Atlantic coast shark population and nursery survey. This shark was caught on a baited drumline, but before we could pull it in an even bigger shark came and bit this one clean in half. There were several larger lemon sharks caught and tagged this same day so one of them may have been the culprit.”

Chris Mull holds up a finetooth shark in Bulls Bay, South Carolina. “We were sampling as part of an Atlantic coast shark population and nursery survey. This shark was caught on a baited drumline, but before we could pull it in an even bigger shark came and bit this one clean in half. There were several larger lemon sharks caught and tagged this same day so one of them may have been the culprit.”

“Basking sharks represent about 95 million years of unique evolutionary history,” Mull told the Bowen Island Undercurrent. “They are slow growing, reach maturity at a late age and also have few offspring. What is really unique about them, though, is that they provide a rare example of filter feeding. This is only seen in two other species of shark and a single family of rays.”

The broadnose sevengill shark and white sharks are other examples of sharks found in Canadian waters that are evolutionarily distinct and imperilled.

Mull recently published a study ranking all 1,192 species of sharks and rays according to their evolutionary distinctiveness as a way to prioritize species for conservation. You can follow his fascination on Twitter at @drsharkbrain.