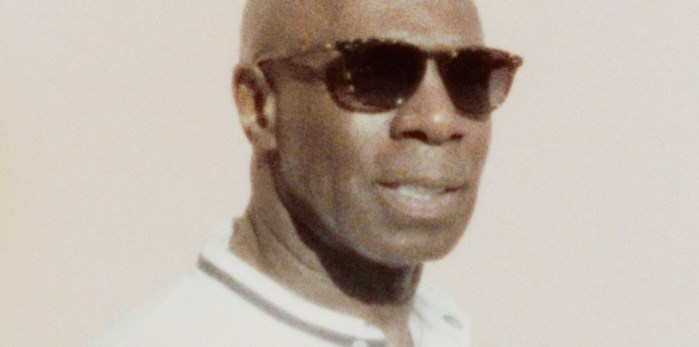

The Day Don Died is a difficult film to write about, despite the fact that the conceit of the film is explicitly laid out in its title. It really is about the day jazz singer Don Stewart died — or rather, the day everyone at Vancouver’s Performing Arts Lodge came to believe that Stewart, one of its residents, had suddenly and unexpectedly passed away.

Short film The Day Don Died details how residents of Vancouver’s Performing Arts Lodge came to believe that jazz singer Don Stewart, one of its residents, had suddenly and unexpectedly passed away.

Short film The Day Don Died details how residents of Vancouver’s Performing Arts Lodge came to believe that jazz singer Don Stewart, one of its residents, had suddenly and unexpectedly passed away.

Am I giving too much away? That’s the challenge in writing about this cleverly crafted short documentary that has its world premiere on Saturday at the Vancouver Short Film Festival. I want people to experience a critical moment in the film as I did: wide-eyed and gasping and desperate to talk to everyone I know all about it.

So I’m not going to tell you how Stewart died. Or didn’t die. Or did he? You’ll have to discover that for yourself at the VSFF screening, or when the film eventually hits the web and Telus Optik.

What’s important is that the residents of PAL — a retirement community in Coal Harbour for retired and disabled artists — believed that he died. And The Day Don Died is about how the news travelled through the community and how the story changed as it passed from one distraught resident to another.

Filmmakers Sean Horlor and Steve Adams had a front row seat to the spectacle. They were originally in the building — an eight-story structure at the foot of Georgia Street — to shoot footage for a National Film Board of Canada documentary about unique retirement communities for queer artists. “We pitched it as a ‘gay Golden Girls,’” says Horlor.

They had seven interviews lined up that day. “From the very first interview they’re like, ‘Have you heard the story? Have you heard about Don Stewart?’” recalls Adams. “And we’re like, ‘No — who is Don Stewart? What story?’ And they’re like, ‘No, no, we can’t tell you, it’s too sensitive, it’s too fresh.’” But then the residents would proceed to tell the story — about how they’d learned that Stewart had died the weekend before.

“And as they’re telling us the story, everyone had their own version of it. We can tell, as we’re talking to different groups of people that the story has completely shifted as people are retelling it.”

“One side of the building had one story, the other side had a completely different story, and we were interviewing people in twos and one person would say, ‘It didn’t happen that way, it happened this way,’” adds Horlor.

When Horlor and Adams left that day, they realized they had a different story to tell, and it wasn’t “gay Golden Girls.” It was about how news — possibly fake news — can spread throughout a tight-knit community.

They reached out to Storyhive, and a year later, they received funding for the project.

News travels fast, but not always accurately, in a tight-knit retirement community.

News travels fast, but not always accurately, in a tight-knit retirement community.

But in the interim, the residents had grown unwilling to talk about Stewart.

“Everybody was on board at first, but then we said, ‘We’ve got the funding for the film,’ and then they said, ‘Well, I don’t know if I want to be on camera, and who else have you talked to? Who said yes?’” says Horlor. “There was a building group mentality.”

But, ultimately, everyone agreed to participate in the film, which weaves interviews together with recreations and musical performances to create something that is at once deeply moving and wildly entertaining.

“We learn better when we laugh,” says Adams. “We always try to find humour in the situations. We really like toying with that line between hybrid and documentary, and creating our own scenes and seeing what we can do with that.”

One lesson that The Day Don Died offers up relates to one of the American President’s favourite phrases: fake news. “As we were hearing this story, we were realizing that people were reacting based on their emotions and not using logic at all,” Adams says. “It was interesting to see how fake news could unfold on a small scale.”

The Day Don Died is the Jan. 26 closing night film for the 2019 Vancouver Short Film Festival.

The Day Don Died is the Jan. 26 closing night film for the 2019 Vancouver Short Film Festival.

The Day Don Died is the Jan. 26 closing night film for the 2019 Vancouver Short Film Festival. The filmmakers and PAL residents — including, just maybe, the titular resident — will be in attendance.

“I think it will be beautiful for them because they get to hear the crowd’s reaction to their performance,” says Adams. “No matter what, a lot of them are still performing. As soon as the camera goes on, they turn into a character.”

Tickets and details at vsff.com.