|

THE OPENING is all about introducing the fascinating, quirky and wonderful people working in and around the visual arts in Vancouver. Each week, we'll feature an artist, collective, curator or administrator to delve deep into who and what makes art happen! |

Instant Coffee is an artist collective originating from Toronto, now based in Toronto and Vancouver. If you don’t subscribe to their weekly listserve detailing openings, lectures, open calls, employment, studios for rent and more about this fair city, you probably should. Instant Coffee is more than just an email however – they have a long CV of work hosting and engaging people in art, in locations all over the world. Regular members of the collective are Cecilia Berkovic and Kate Monro (Toronto), and Jinhan Ko, Kelly Lycan, Jenifer Papararo, and Khan Lee (Vancouver). I sat down with the Vancouver members in a nook they had created in their new studio.

The Vancouver members at Light Bar during the 2010 Olympics. Photo courtesy Instant Coffee.

Jinhan Ko: We went to [UBC art history professor] John O’Brian’s lecture on Tuesday.

Anne Cottingham: How was that? I wanted to go to that.

Jinhan: It was really different. I thought it would be more about the Cold War. But I don’t really know his writing. Otherwise maybe I would have known that.

Jenifer Papararo: Well it was one talk. I mean we only heard one out of three. I think it was really hard to gauge. It was pretty specific. This one he was making an argument about photography in relation to the atomic bomb and its development, but it was a very technological discussion of photography. It wasn’t an aesthetic one necessarily. In the question period he articulated he was interested in both of those things, in melding both of those things together. We really only got one side of it for the talk.

Kelly Lycan: And then too the questions brought out a lot more information.

Jinhan: Part of the reasons I wanted to go were totally selfish reasons. For example, like the one project we made was Disco Fallout Shelter, and it was our sense of being nostalgic for the Cold War era. Because officially it ended when the wall came down ’89, the Berlin wall, and since then it’s like… there’s this sense that the left has failed, that capitalism is winning. So I was kind of curious about being nostalgic for something. Something that’s recently passed like the Cold War era. You know like living with the bomb. So that was the bunker, living with the bomb, the fall out shelter.

Jenifer: I think our interest in the fallout shelter took on a more domestic scale. How it infiltrated everybody in their household and how it shifted it or affected the way that they lived. And how they were actually used. So even though it was this sweeping fear, and this global perpetuation of fear… how it actually was articulated in people’s backyards, and how it was used aesthetically and architecturally mainly as a site of leisure in the end.

Jinhan: Particularly in North America. Because the bomb never came this far.

Khan Lee: Oh that’s true actually.

Jenifer: But all the hype about it, even very close to the site that we built the first one. The CBC themselves built one and had a family live in it.

Jinhan: But that was in the ‘50s right?

Jenifer: Yeah, it was a long time ago. They did studies, these stats projecting what would happen if a nuclear bomb was dropped in the area, and how many people would die and all this, and had these sweeping predictions. So they were inflating that fear for sure.

Kelly: But I mean that’s also, the fear… there’s a certain living with the fear now. Because it really got perpetuated after 9/11.

Jinhan: Well that’s a different kind of fear.

Kelly: Really?

Jinhan: Yeah. The interesting thing about the Cold War was that we knew the enemy. The enemy was very palpable, over there. Whereas contemporary fears are more abstract.

Kelly: But you know it’s still the same, the propaganda, the fear.

Jenifer: It was timely for us, the war in Iraq and against terrorism, watching people go out and buy duct tape and anthrax things, and just watching fear spread and incite such violence. Even though there were these protests, the world’s biggest protests, they were totally ineffective.

Disco Fallout Shelter. Photo by gadjo via flickr.

Anne: Disco Fallout Shelter was locked right, nobody could get in? I was really interested by that. When I read that, it was like there was this party downstairs, that it was this community that nobody could get into. This cool party that nobody could get into.

Jinhan: Yeah that was kind of what it was.

Jenifer: This exclusivity.

Jinhan: I think we were playing with the survival of the collective. But at the same time ended up being the cool party. Or “this is the surviving party” kind of thing.

Khan: And also, when you were inside, I just couldn’t trust anyone. Who do you know are your friends or not just by the sounds of banging? Can’t just let them in.

Jenifer: But we had a good time in there.

Anne: Were you always in there?

Jinhan: No. But in a way there’s a connection between this nook and a bomb shelter. Because… the first time we built this, it was for this show in Columbia, and we built one of these. The idea was we were going to have dinner parties in here. But of course, you can only fit maybe 4 or 5 people like this. It ended up spilling over into the rest of the gallery. And that was kind of the irony. Because the idea was that the cool kids get to.

Kelly: The idea was that we were having it to have artists, like having studio visits with artists.

Jinhan: Well that was another use too, but a dinner party is a little bit different.

Jenifer: The space was to be used and people did use it. The staff had lunch there, and people came into the space. But yeah for us, when we were there...

Kelly: We activated it, and other people activated it.

Jenifer: We did studio visits with people from Medallin, but also people who were in the exhibit with us, which was an international exhibition. It was also… our interest is in looking at social spaces and what that looked like. This nook that was in my old apartment was a very social space, it was a place that I always socialized and we socialized in. And just looking at it as that, but then realizing that if you’re not in the nook then you’re outside of the nook.

[Laughter]

Anne: You’re somehow excluded.

Jenifer: Yeah, so we wanted to kind of explore that, because you know, people have kind of talked about our practice as being all-inclusive and we always invite and incorporate other people into it. But it’s never been a free for all, there’s always been choices on who participates. And generally it tends to be artists. Our audience mainly tend to be people involved in the art scene. Although we do expand outside of that for sure.

Kelly: We always have some hospitality outside of the nook. In Columbia we had these padded platforms that were on wheels, and so people could lay on them and read. A lot of stuff happened on those that we didn’t really control. So we still had outside hospitality.

Anne: I guess that makes me think of Light Bar too. Like, behind the bar was like this little nook where you guys all hung out, and then the rest of the space was where everybody else hung out.

Kelly: We were working though!

Khan: Some cool kids tried so hard to get behind the bar, but not everyone made it.

Jinhan: Well, actually it was kind of easy to, because all they had to do was just volunteer to bartend, and then it’d be like “Woohoo, ok you get to bar tend now!”

Anne: You’ve done Light Bar a ton of times, but is the biggest installation the one you did during the Olympics?

Jenifer: Yeah definitely.

Anne: Do you think you’ll ever do it again?

Kelly: Well we’ve done it twice.

Jinhan: Actually three times.

Anne: To that scale I mean?

Jenifer: We opened it in Victoria. It was definitely a smaller scale. We didn’t take over the space in quite the same way. We did use the bar of course. But yeah that’s the first time we did it to such a scale, and that consistent of events for that long of a duration, and that many people came.

Light Bar during the 2010 Olympics. Photo courtesy Instant Coffee.

Jinhan: You know actually, in hindsight the location we had in Victoria was really fantastic because it was kind of close to party central but it was kind of off the beaten street. It was an unoccupied space, but it was maintained by the mall. So it was well kept. And obviously the gallery and the management company had a relationship. So that worked out. I mean we got to try a lot of different things. I think space wise, Victoria was probably bigger. I mean, square footage wise.

Kelly: Hm, I don’t know.

Jenifer: No.

Kelly: It was just the layout.

Khan: The ceiling was higher.

Jinhan: We actually had back staging. A staging area. But maybe it was comparable.

Jenifer: That’s where we built the Disco Fallout Shelter. So we turned the light bar in Victoria into a partial studio.

Jinhan: And then shot the video. So in a way it looked like we were living in the shelter but it was just a video.

Jenifer: We had a kiosk at the end of a yellow brick road that was leading to the Disco Fallout Shelter. And in that we did 4 different views of us in the Fallout Shelter, and we built that as a set. And then we stayed in there for a duration of time. Played records, danced, ate pasta, napped, we cried, laughed.

Jinhan: Why did you cry?

Jenifer: I was kidding!

Khan: Didn’t you fight?

Jenifer: We didn’t fight, but it was pretty funny, it was pretty high anxiety going in there. We were just in the back of the studio, and there was no roof on it, it was just all set up for the camera, and we had troubles breathing. So we opened the wine right away. It was an elimination process – can you survive with that set?

Jinhan: Did I tell you there are six Instant Coffee members?

Anne: I know there’s the four of you here and then there’s some in Toronto.

Jinhan: Two in Toronto. Kate and Cecilia live in Toronto.

Anne: Were you all based in Toronto before?

Jinhan: It started out in Toronto.

Anne: Why did you come here?

Jenifer: Well, basically I got the job at the CAG [Contemporary Art Gallery], so Jin and I came out here. And we set up camp. Then we met Kelly and Khan.

Anne: How are you finding it from Toronto? Between art scenes? Negotiating those communities I guess?

Jinhan: It’s so different really.

Jenifer: I guess we haven’t really thought about the difference so much lately. But when we first got out here we noticed that in Toronto it’s a very scene-based art scene. Here it’s more mentorship based so there’s a real focus on history and a perpetuation of that history and a dedication to it. In Toronto there’s an awareness of history but it’s way more about different social scenes. And different ideas.

Jinhan: Art as being more social. Certain openings are a big event.

Jenifer: It’s pretty social here too.

Jinhan: Oddly more so.

Jenifer: One thing I did notice recently - since we came here we’ve started going to Europe way more often. When we were in Toronto, we were going to South America and Mexico and we were showing there and in the States. And since we got here we’ve been consistently going to Europe. It’s funny, I’m not exactly sure that’s a difference between here and there, it just kind of seems somewhat related.

Jinhan: That’s an interesting point. I don’t know if that’s true but that’s an interesting observation.

Jenifer: I mean it’s true, whether it’s related… So it’s just different here. I mean this is the first time we’ve ever had a studio so we’re definitely making sculptural work and have been more formally driven since we’ve come out here.

Anne: Right, like your show [at MKG127 in Toronto]… make more formally driven work out here but then show it in Toronto…

Jenifer: That’s true! Yeah we haven’t had a show here in a while. I guess the Light Bar was our show. So it hasn’t been that long.

Jinhan: We’re kind of involved in more public art projects.

Jenifer: Yeah that’s true. Working with Translink and the city.

Anne: I actually wanted to talk about that because I know a lot of your signs were vandalized. I was wondering how you felt about that. Did you want that to happen? I mean, probably you knew it would happen.

Kelly: I think it was inevitable.

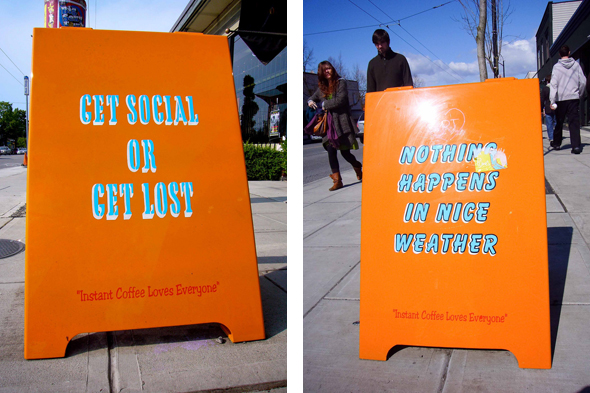

Two sandwich boards from the Main Street installation. Photos by sashafatcat via flickr.

Jenifer: Well it was so low to the ground, we wanted it as a space that would be graffiti’d and tagged, but there was supposed to be… the City was supposed to clean it every once in a while, and then they didn’t do that. So that was the disappointment. So without any maintenance at all it got out of control.

Kelly: But also people vandalized in ways that we didn’t imagine, like kicking them in so they got totally dented. Scratching... we expected some stuff that we could maybe take off, but the vandalism went to a degree we weren’t expecting.

Jinhan: I think we would have designed it a bit differently knowing what we know now. Like having the slogans show through somehow even if somebody tagged it. Or maybe it being the venue for people to post. Or just kind of play around with the eventualities of street.

Jenifer: Make it easier to graffiti in a way, and easier for us to come and take it over again. That shift back and forth. Basically I feel like it… if it had been maintained, it would have stayed cleaner. But it was always only a semi-permanent project.

Jinhan: It was also kind of an experiment on their part as well. I mean I didn’t realize this, but Translink and those guys had never actually tried to have public art. So it was learning on their part as well. In a way it was a positive experience. But the difficult thing is that they’ve stopped the project since.

Anne: Yeah, I thought it was supposed to go on for a while.

Jenifer: There were supposed to be three other projects after ours, four in total. One was going to be a group show and then two other solo artists that they had picked. I’m not exactly sure what fell through. I think the economy for one, and Translink is broke. I’m sure that has something to do with it. That’s the only reason I can see for it falling apart.

Anne: I’ve noticed that your work is really community-based, obviously that’s on purpose. I’m interested in this idea of community involvement and the different ways that you’re exploring it. Like the Watts Towers - somebody who was trying to be involved in his community and was basically denied. Light Bar - obviously that’s a huge involvement. And Disco Fallout Shelter, also a denial of involvement in a way.

Kelly: I think we’re interested in a pretty specific community.

Jinhan: The art community, for example.

Anne: The art community? How?

Kelly: I mean, that’s who we think our audience is, and what we gear our work towards.

Jenifer: We really want to talk to who were generating for. The art community view - it can shift from music to architecture to design. But we do tend to try to engage an audience of people who are also producers, who are also making their own work, or have things to show. So we create cultural venues. I think that would probably the most consistent thing that we do. We’re interested in opening those spaces to make culture happen, to see what we’re interested in seeing, but also as a necessity, coming from a place in Canada where those things are few and far between. Also our history, it’s a political gesture to create a space for culture to happen.

Kelly: But that’s also part of Instant Coffee’s.... it defines itself as a service-oriented collection. So not only with the listserve, but I really felt that the Light Bar was really about that. Because people really needed a space like that in this city and you could tell by the reaction to it that it really did provide a necessary service. So that’s important. I think our interest is to have it manifest in other cities.

Khan: Locally I kind of think that it influenced quite a few different people to think about potentially creating a space that serves a similar kind of function. The idea of being able to do such a thing sort of manifests itself.

Kelly: Yeah it kind of gave permission or possibility.

Jenifer: And it’s not like these things hadn’t been happening. There are these underground places here, but we were just able to do it very publicly. Not that we wouldn’t do it above board as much as we could, but we still got busted by the police all the time and got hassled by the fire department.

Jinhan: But that’s part of the climate of Vancouver. It’s very strict.

Jenifer: I think that’s kind of interesting that [Vancouver city councillor] Heather Deal is really trying to shift those laws and acknowledge the fact that Vancouver has a ‘No-fun City’ slogan, and trying to create at least these small spaces where that can be usurped.

Anne: I know you guys have your own separate practices or your own separate things. Do they tie in really well with what you do as a collective?

Jenifer: I guess Jinhan is the only one without a bifurcated practice. So Jinhan is the only one that’s Instant Coffee 100%. All of us have other practices.

Jinhan: But it’s also different. I mean part of the reason we can work as a collective is because those different skills feed into making a collective. We tend to take on these installations, things that have different components. There’s an organizational aspect, there’s a building aspect, there’s media components. So in a way, the different characters that make up the collective, there are certain roles that people play. Instant Coffee first started with a different make up. Some people have come and gone. Partly because their fit was good at the time and then the group can change. Or you know, “I want to do different things” and they just move on.

Jenifer: We’ve always been interested in incorporating people with different skills and different interests. So we started off with a designer and you know I’m a curator, and Jin’s a visual artist and so is Kate. But Kate was also really involved with online media. And so we kind of came together like that. But our interest is really in the visual arts. Before we even knew what we were doing or why we were even coming together under this name of Instant Coffee, we were just using it as a place to aestheticize. We were creating whether it would be an identity or an aesthetic and just kind of hashing it out that way. Figuring out what we wanted to do from there.

Kelly: Intentionally using some of the advertising models. Addressing how that information is disseminated.

Jinhan: In the beginning there was a lot of discussion around this idea of branding. Because when you’re starting out making new work and starting a collective, how do you promote yourself and how do you locate your practice within the rest of the community? There were a lot of discussions around this. When Jenifer and I were first talking about Instant Coffee, there were a lot of discussions around art systems. How does art get made, how does it get distributed, how does it find this audience? Then looking at different models.

Jenifer: We talked about it as trying to jumble it up. Where it would get produced, where it would get viewed, how it would get presented. Would it all be mixed? The order might be different when you produce it in your studio than when you present it in the exhibition space. And then it gets distributed in text and advertisements. So we wanted to play with all those parts and then mix it up. Things didn’t have to happen in such a particular order - they got made at the same site where they were being presented. And for a long time the exhibition space was our studio, and that was really one of the few times that we would get together and build together. Things have shifted since then.

Kelly: But still addressing that consumer culture that comes through the sandwich boards, using slogans a lot became a real anchor early on. It still kind of carries through. That was a part of the interest of using sandwich boards like that.

Anne: What about the use of light?

Jenifer: I guess that would really be about Vancouver! [All laugh] That’s borne of necessity.

Kelly: That was another service provided.

Jenifer: When Jin and I moved out here, it was the rainiest year. That September it rained 30 days in a row when we landed. It was one of the rainiest years that Vancouver had in a long time. The next year was the same and the next year was the same and so it was just something we had to address.

Khan: I never thought of it this way, but the place that these guys moved into when they first moved to Vancouver actually did have a huge bank of lights. It was like, super intense. Once you get in there and turn on the light it was really intense. Maybe subconsciously... then there was Light Bar four or five years later.

Jinhan: That’s true actually, it was like a bunker.

Khan: It was like a bunker.

Kelly: Good thing you moved into that place.

Anne: So what’s next?

Jenifer: That’s a good question. The Watts Towers are really what’s on our minds right now.

Kelly: We have a public commission in Edmonton. It’s a recreation centre, and we’re doing this... it’s a three-dimensional afghan sculpture mural. It relates to the billboard. You know the billboard that turns 3 sides, that’s basically what the model is. It’s basically afghans on each side, but people can access it so they can spin the sides around.

Jinhan: There’s no motorized system.

Jenifer: And then we’ll have three different designs so people can change it. So we’re doing that for a community centre in Edmonton. And then we’re doing the Light Bar again in the Netherlands. And we’re working on our studio. How we can shift it up and actually invite people in here and make it a social space. Or make it some sort of place for commerce to happen. So we’re working on how to try to figure that out. We also enjoy hosting. It’s key. It’s important to have a space where we can invite people in.

Kelly: The space would feel underused if we didn’t host.

-------

Instant Coffee have just completed a solo show based around the Watts Towers at MKG127 in Toronto. They are working on the aforementioned public sculpture in Edmonton, planning a ‘mock retrospective’ at Western Front, and designing an installation for the next Powerball at The Powerplant in Toronto. Their storefront studio is being turned into an art multiple shop, to be launched during this year’s Powell Street Festival (July 30-31), and will be hosting some art and music events in the studio prior to that. They also host Whittling Wednesday’s at their studio every second week.

To sign up for their listserve or for more information, visit their website at instantcoffee.org. They can also be followed on Twitter @InstantxCoffee.