The first time my mother visited the American Hotel at 928 Main Street she was seven years old and wearing a shiny new faux-snakeskin jacket. A trip to the city with her dad usually meant a special visit to Woodward’s or to the Normandy restaurant on Granville Street, so she had every reason to believe she’d be showing off her new duds. This day would not be one of those days.

My grandfather came from a very, very poor family — one of those 1930s Irish immigrant families mired in addiction and a litany of Angela’s Ashes-y childhood horrors. After a young adulthood of moonshining and illegal Chinatown gambling dens he conquered his demons when his kids were young, and gave up the drinking and the cards for good. But his family? They didn’t. By the early 1970s, when this story takes place, he had numerous cousins, aunts and uncles living hand (and bottle) to mouth in the early SROs of the Downtown Eastside.

Of course, back then the department stores still lined Hastings Street and the cafes were all still open and the area hadn’t yet adopted the “Eastside” part of its name — it was still decidedly “Downtown” and so my wee little mum had every reason to believe that the afternoon would be spent shopping. Instead, when my grandfather parked the car he looked down at her. “Hold my hand. Don’t let go of my hand.” Into the lobby of the American they went.

The 900 and 1000-blocks of Main Street are lined with the remnants of a series of hotels and rooming houses built in the first two decades of the twentieth century. The area had long been a hub for travelers coming from New Westminster and the US border, and when a huge part of False Creek was filled in to make room for the new Pacific Central and Great Northern Railway train stations during the first World War, the area became even more integral to the city as a convenient place to stay.

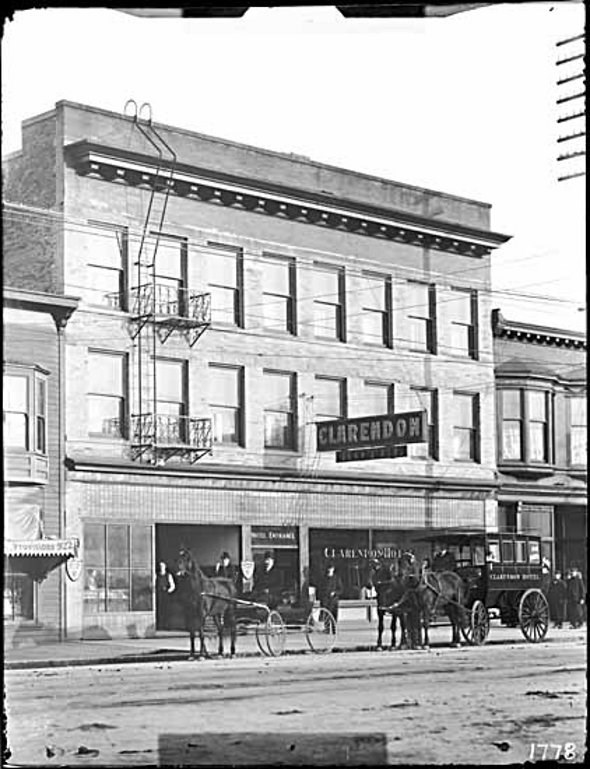

It was in 1907 that the American (originally the Clarendon) and the Ivanhoe (VanDecar) Hotels were built, followed a few years later by the Cobalt (Royal George) in 1911 and the BC Electric Railway Men’s Quarters in 1913. While none of these lodging options were ever posh, they were clean, reliable places to stay.

By the 1970s, however, the whole area was experiencing an economic shift. In addition to the beer parlours and nightclubs that the East Hastings Street has always been known for, hard drugs began to stake their claim. The rooming houses and cheap train station hotels that were the only housing options many could afford began to take on a more dangerous air.

“I remember the hallway,” my Mum recalls, “it was musty and dark and people had their doors ajar. I wanted to peek inside but my Dad pulled me away. ‘You’ve got to respect people’s homes, no matter where they are,' he said to me.”

While my Grandfather believed in respecting everyone’s home, that didn’t mean he was happy that his sweet old toothless Auntie Annie and her hardscrabble alcoholic daughter Elsie were sharing a room in the hotel. Though they doted on my mother and offered her treats, it was clear that they were living in abject poverty, a reminder of my grandfather’s not-too-distant past.

“It wasn’t just the Old American,” my Mum remembers, “we used to go to the Cobalt and the Ivanhoe as well, sometimes even the Balmoral or the Patricia. Uncle Shorty, my dad’s uncle — he was down there too. They all were. Dad would bring them food and money, but they would just spend it on booze. It was sad.”

It was sad, indeed, until my grandfather fought and clawed with the early version of BC Social Housing to get his aunt and uncle (who were brother and sister) into subsidized seniors care closer to him in Surrey. It was there, next door to the IGA on 128th Avenue, that I remember going to visit Uncle Shorty in the 1980s (Auntie Annie had passed away). He was still on the sauce, but safe and warm and cozy in a little apartment far from the American Hotel. He loved my Grandfather like a son for everything that he did for him — for believing that he deserved better.

I ask my Mum why she thinks her dad took her down to those hotels in the Downtown Eastside, subjected her to such harsh realities so early in life.

She pauses.

“He wanted to show me that there were good people there. That even if you had a hard life, or were down on your luck that didn’t mean that you couldn’t be a sweet, kind person. He believed in family — that even when we were stepping over needles and broken bottles in the hallways, on the other side of those doors were good people. They were important, too. They were our family.”

In 2006 the city revoked the liquor license at the American Hotel and the owners evicted the residents. The hotel sat empty for nearly five years and to be honest, I was sure that any day I would see a Permit Application affixed to the front of the building asking for permission to tear the place down. Quite the opposite has happened.

Steven Lippman, he who resurrected the London Pub (and plans to re-open one of my very favourite Vancouver landmarks, Save On Meats this Summer) has just celebrated the grand opening of the space as the Electric Owl, a Japanese izakaya inspired restaurant/live music venue. Upstairs are 42 rooms (fraught with their own controversy) in the $400 to $750 a month range. Undoubtedly they will be cleaner and safer than the rooms that my Auntie Annie, Cousin Elsie and Uncle Shorty once called home. It's a new chapter in the checkered life of this 104-year-old building.