Daily air quality advisories are stretching into the double digits, while health indicators have reached dire levels that prevent even the fittest among us from being outside for extended periods.

Metro Vancouver was under its eighth straight day of an air quality advisory Tuesday, with the same precautions being emphasized daily: avoid prolonged physical exertion outdoors, keep tabs on the elderly and infants and seek out clean air in malls, libraries or community centres.

The photo on the left was taken on Aug. 17 near the north end of Commercial Drive looking west towards downtown. The photo on the right was taken from the same vantage point on Aug. 20. Photograph By JENNIFER GAUTHIER

The photo on the left was taken on Aug. 17 near the north end of Commercial Drive looking west towards downtown. The photo on the right was taken from the same vantage point on Aug. 20. Photograph By JENNIFER GAUTHIER

Last year was record setting in the amount of air quality advisories issued, as 19 warnings went out. The previous record, set in 2015, sat at 10. Central and southeastern B.C. have it infinitely worse, to the point of the sun being completely blacked out for extended periods.

Metro Vancouver climate engineer Francis Reis expected local advisories to continue until at least Wednesday if not into Thursday and Friday as well.

More than 560 fires are burning across B.C. and 500,000 hectares of forest are gone. Firefighting costs alone since April 1 are veering towards $250 million.

Satellite images show the smoke from B.C. wafting all the way to Ontario and across the northern U.S.

Considered an anomaly even 10 years ago, a summer in B.C. without these conditions may not happen again for a generation.

How has this happened?

According to UBC professor Lori Daniels, the reasons are many and complex.

The easiest piece of the puzzle is population. There are simply more of us, in more pockets of the province, which inevitably increases the chance of man-made fires. Varying estimates suggest anywhere between 30 to 50 per cent of the current fires are caused by people.

Climate change is another easy and obvious answer, but far from the only one. A professor of forest and conservation sciences, Daniels says precursors to today’s fires were seen more than two decades ago.

The mountain pine beetle epidemic that started in the 1990s was a substantial sign of things to come. For starters, it killed millions of hectares of trees and created an abundance of fire fuel across B.C. that was never properly disposed of on a large scale.

The beetle’s proliferation also highlighted how certain trees — lodge pole pine, for example — were planted above others, namely for economic reasons. Those decisions created uniform forest types, which in turn, created untold amounts of fuel and a weakened resiliency to fires.

Tree species like aspen or paper birch weren’t planted with the same frequency as Douglas fir, cedar or other types of wood coveted by industry. In some instances, aspen and paper birch stands were killed off or overharvested. Referred to as broadleaf trees, those species are critical to large stands of trees: they’re less prone to burning, create shade on the forest floor, reduce temperatures and promote more humidity.

The ideal scenario, according to Daniels, is a forest full of mixed species and mixed densities of those species. That diversity allows for more fire resilience, more nutrients in the ecosystem and less fuel.

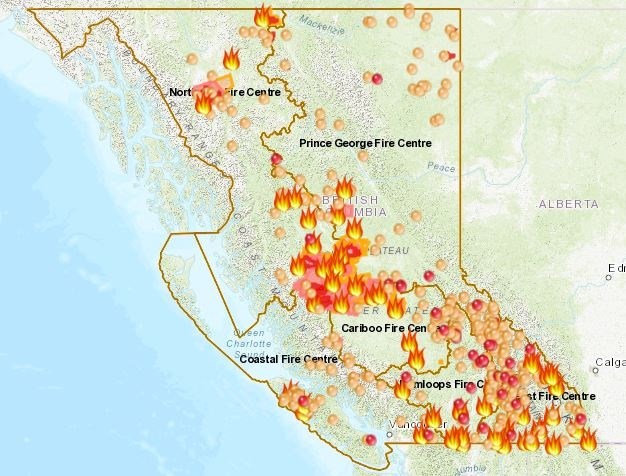

This map provided by the province shows the number and severity of wildfires across B.C. as of Aug. 21.

This map provided by the province shows the number and severity of wildfires across B.C. as of Aug. 21.

“If we’re just going to plant primarily lodge pole pine over large areas in our Interior forests of B.C., we’re setting ourselves up so that the next generation, our kids and grandkids, will be fighting off the next mountain pine beetle epidemic and all those forest fires,” Daniels said. “We have to learn from those mistakes and do better.”

Another mitigating factor is the nature of how we fight fires — in short, we’ve gotten too good at it.

Daniels said some remote fires should left to burn off, albeit in a controlled manner, so new ecosystems can start from scratch. That practice has already begun in parts of B.C.

“It seems kind of wasteful in the short term because you create all this smoke and you burn all this timber,” she said. “But it creates diversity in the landscape. If you let a fire burn, it rejuvenates a new forest.”

Another remedy is the immediate need for fuel mitigation around B.C.’s cities and towns. Daniels pointed to a 2004 study that suggested 1.6 million hectares of forested areas around B.C. are on the cusp of urban areas and chalked full of fuel. Those forests need to be thinned out, and the fuel on the ground removed before any sort of predetermined burn can happen.

That process also includes an unpopular notion, at least politically — cutting a bunch of trees down.

Where older, thicker trees are more fire resilient, younger trees often act like wicks that pick up flames from the forest floor and transport the blaze up in to the tree canopy.

“We need a substantive investment, in the order of billions of dollars, in order to treat those fuels, to create safeguard zones around those communities,” she said.

Those costs will rise exponentially under the status quo approach. Estimates for a full recovery — including rebuilt infrastructure, human health costs and job loss — from the 2016 Fort McMurray fires are in the range of $10 billion.

Firefighting costs alone from last year’s wildfire season in B.C. have been pegged at $580 million. Daniels said that number can jump anywhere from two to 30 times higher once other factors like rebuilt infrastructure and human health costs and are tallied.

Places such as California and parts of Australia that were once seasonal fire worries are now year-round concerns. Fire season in those locales is every day, every year.

Daniels doesn’t foresee that happening in B.C., largely because we’re too far north.

But a summer without haze is a different story altogether.

“I think we’ve crossed a threshold. The tipping point is happening,” she said. “Even in the past we’ve had variations from one year to the next. But I think what we’ve seen in the last 15 years is more of these years with fairly big fires with greater impacts. I think that part of it is here to stay.”