It almost seemed like the world was changing in fast-forward.

The Sony Walkman had just arrived on the scene, the second wave of punk rock was coming, oil prices were at record highs, the political landscape in the Middle East was unraveling and Pierre Trudeau was out of the Prime Minister’s office — albeit briefly — for the first time in a decade.

After 40 years, China Creek skatepark remains an integral space for Vancouver’s skateboard community, including Jeff Cole, Scott Kiborn, Peter Ducommun — a.k.a. “P.D.” — and Alexis MacRae. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

After 40 years, China Creek skatepark remains an integral space for Vancouver’s skateboard community, including Jeff Cole, Scott Kiborn, Peter Ducommun — a.k.a. “P.D.” — and Alexis MacRae. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

The year was 1979 and a small patch of park near Clark Drive and Broadway had a similarly life-changing effect on generations of Vancouverites past and present.

The China Creek skatepark turns 40 this year, and members of Vancouver’s skating community will gather July 19 for a birthday bash at the Smiling Buddha Cabaret (SBC).

In advance of Friday’s shindig, the Courier spoke to members of the Vancouver skateboarding community who were there long before the park was built.

Between the five of them, they have roughly two centuries’ worth of skating and skateboarding knowledge.

Peter Ducommun, aka P.D., achieves maximum zen as Scott Kiborn shreds the bowl behind him at China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Peter Ducommun, aka P.D., achieves maximum zen as Scott Kiborn shreds the bowl behind him at China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Their rap sheets are as follows:

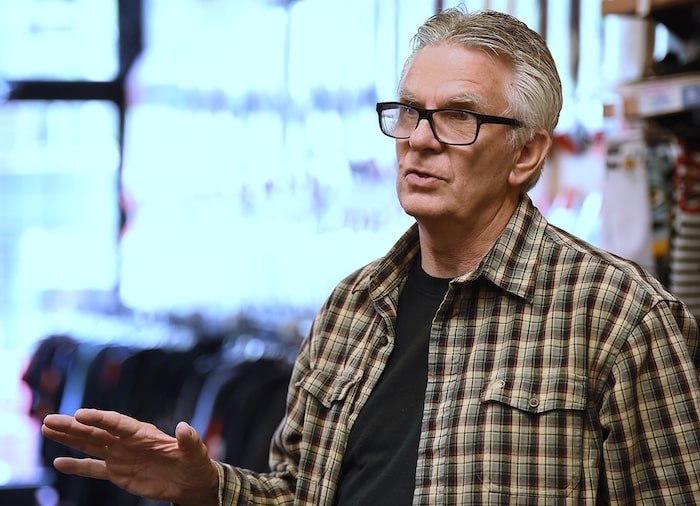

Peter Ducommun, a.k.a P.D.: 57, owner of Canada’s oldest skateboarding brand (Skull Skates); started skating in 1973; runs P.D.’s Hot Shop on West 10th Avenue.

Monty Little: 72, born in the U.S and arrived in Canada in 1965; started skating in 1963; helped design China Creek; began organizing skate contests across Western Canada in the 1970s.

Scott Kiborn: 56, moved to East Van from Cloverdale in 1977; started skating in the mid ’70s; claims to have skated China Creek every day during the 1980s.

Jeff Cole: 45, arrived in Vancouver in the mid-1990s; started skating in 1985; teaches kids to skate via his company UnderToe Skateboard Academy; president of the Vancouver Skateboard Coalition and works at P.D.’s Hot Shop.

Alexis MacRae: 28, moved to Vancouver six years ago; started skating in the late 1990s and only took to China Creek three years ago; competes in local events and contests.

Peter Docommun, aka P.D., gets after it at the China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Peter Docommun, aka P.D., gets after it at the China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Each was asked to put into words what the park means to them individually, and to the collective skateboarding community. Cole’s answer, in particular, resonates with everyone.

“You might see it as a sports facility like a basketball court or a tennis court,” he said.

“But China Creek, since its beginning, you can just show up and there are people of all ages, ethnicities and orientations hanging around or skateboarding. It’s a community centre.”

Skateboard enthusiasts let their sentiments be known about the possible closure of the skateboard bowls in China Creek Park on May 7, 1987. Photo by Ian Smith/Vancouver Sun

Skateboard enthusiasts let their sentiments be known about the possible closure of the skateboard bowls in China Creek Park on May 7, 1987. Photo by Ian Smith/Vancouver Sun

Boom and bowls

The area near Clark and Broadway was a lot of things long before skating arrived on the scene. It was farmland, a garbage dump, a drainage hub for numerous local waterways, a velodrome and home to the Clark Park Gang.

P.D. suggests the generally accepted birth of skateboarding is sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s, though skating was still in its incubation phase on Canada’s west coast in the early 1970s.

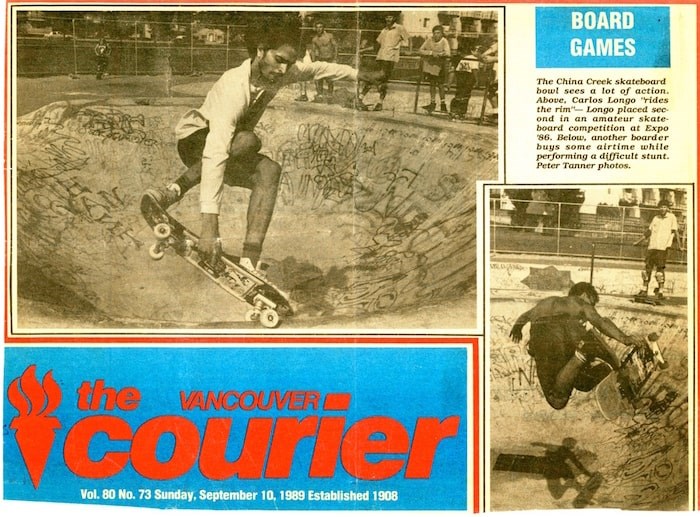

Carlos Longo skates at China Creek in 1987. – Submitted photo by P.D./Skull Skates

Carlos Longo skates at China Creek in 1987. – Submitted photo by P.D./Skull Skates

It was a time of massive sea shifts in skate technology, coupled with a confluence of environmental factors: water shortages in California meant lots of empty pools and reservoirs; wheels shifted from clay to urethane; the Duraflex Cal-240 became the board to own in 1975 and skate mania was on its way.

It’s around this time that Little started to become the lynchpin of the Vancouver skateboard community. He organized the first B.C. Skateboard Championship in Stanley Park on Sept. 11, 1976.

In attendance was Ray Addington, president of Kelly Douglas and Company, which owned Super Valu stores across Canada. His two sons had taken part in the Stanley Park competition, prompting Addington to ask Little to help him promote skateboard safety through a series of skateboard contests.

“He called me and he said he was tired of the bad rep going on in the papers and on TV,” Little recalled. “He said, ‘I want Supervalu to go down in history as the people who taught skateboarding safely. What do we do?’”

From 1977 to 1979, Little organized more than 150 contests in Super Valu parking lots across the country and the boom was born.

David Hakkarainen works out his $300 skateboard in China Creek Park on June 8, 1987. – Rick Loughran / Province

David Hakkarainen works out his $300 skateboard in China Creek Park on June 8, 1987. – Rick Loughran / Province

“It was the most successful promotional event that Super Valu ever did — nothing even came close,” Little said. “Every town we went in to, every radio station, TV station and newspaper was there. We shut whole towns down to watch seven kids compete. It was crazy.”

The country’s first outdoor skateparks arrived in three successive years: West Vancouver in 1977, North Vancouver in 1978 and China Creek in 1979.

“There was this sort of greaseball scene — the dudes with the cut-off sleeve jean jackets and the deck of smokes doing one-handed wheelies on 10-speeds with the bars flipped up,” P.D. recalled. “People went from being these long-haired greaseballs to chopping their hair off and starting punk rock bands and going to punk rock shows. That was the backdrop that skateboarding kind of grew out of in this town.”

Having designed both parks in West and North Vancouver, Nelson Holland approached Little for advice when it came time for China Creek’s design. Holland’s preference was to create a “Key Hole Pool” layout and Little referenced photos of a reservoir in southern California that would eventually help shape the two bowls that are there today.

Fanfare and excitement ruled the day in late August 1979, but the opening press conference did not go according to plan. Chunks of concrete disintegrated as the assembled skaters went on their inaugural runs.

Monty Little helped make skateboarding culture what is today through his many promotional efforts dating back to the 1970s. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Monty Little helped make skateboarding culture what is today through his many promotional efforts dating back to the 1970s. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

“There were people who came at nighttime after the top coat went on that were skating it, but the concrete didn’t marry properly to the surface,” Little recalled. “It’s opening day, people from the city are there and it’s falling apart. Not the best PR. It was devastating.”

A fence went up that was patrolled day and night by the locals, and the new top coat set within three weeks.

Into the ’80s and beyond

With a new park in tow, Vancouver’s first wave of skateboarding rock stars rose to prominence such as Cory Campbell and Carlos Longo.

“Cory Campbell was the dude,” P.D. said. “Imagine looking at a magazine and seeing people doing these things and you want to do these things. You’re skateboarding but you’re not doing the things Tony Alva is doing and then all of a sudden you see this guy right in front of you doing that stuff. That was Cory. It was mind blowing s***.”

1980s Vancouver skateboarding luminary Carlos Longo on the cover of the Vancouver Courier in 1989.

1980s Vancouver skateboarding luminary Carlos Longo on the cover of the Vancouver Courier in 1989.

Cole found his way onto a board six years after China Creek opened. It was 1985, he lived in Ucluelet and Back to the Future was in theatres. A singular skateboard was brought to his elementary school, and a contest was held to see who could make it down a nearby hill without stopping or falling.

“I made it to the bottom in one try and nobody else had made it,” Cole said. “There was a feeling, there was a freedom and all this stuff that was encapsulated in this hundredth of a second that I wanted more of instantly. I begged my dad to buy me a skateboard. I was the first of my crew to buy a skateboard and I never looked back.”

Despite the emergence of skating luminaries such as Tony Hawk and Rodney Mullen, Kiborn recalls something of a lull around the time Cole was getting started. What was cool one year started to fizzle out the next.

“In the ’70s when I started, it was fad just like hula hoops — and then it died,” he recalled. “In the ’80s I’d ride China Creek all the time and there were only a few regulars who were coming. Towards the end of the ’80s and the early ’90s it got big. The punk rock, grungy attitude of the ’90s made it so marketable.”

Mainstream exposure

Peter Ducommun, aka P.D., runs the oldest skateboard brand (Skull Skates) in Canada. His shop is located on West 10th Avenue near Alma Street. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Peter Ducommun, aka P.D., runs the oldest skateboard brand (Skull Skates) in Canada. His shop is located on West 10th Avenue near Alma Street. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Much like skateboarding in general, China Park’s continued glory days were never a guarantee.

The park has faced threats of closure a handful of times — safety was a big concern in the mid-1980s and the spectre of redevelopment loomed in 2005 and 2006.

As the sport gained more mainstream exposure, skaters started making huge sponsorship money. Some felt that the essence of skateboarding was being lost or sacrificed at the altar of the dollar.

To that end, P.D. is no fan of skateboarding’s debut at next year’s Summer Olympics. He doesn’t want the sport affiliated with Coca Cola, an Olympic sponsor he refers to as “poison.”

This is where a couple of fool proofs enter the picture. That skateboarding can be insanely difficult, time consuming and painful filters out many non-believers.

Alexis MacRae catches some air out of the bowl at China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Alexis MacRae catches some air out of the bowl at China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

“You can’t fake being a skateboarder,” P.D. said. “You can look like a skateboarder, but to ride a skateboard, there are no shortcuts.”

Skateboarding’s self-regulating, rules of engagement also come into play. It happens at parks and just about anywhere else the sport goes down.

P.D. explains it like this:

“If you show up to a spot and you’re not a local, it’s not an automatic,” he said. “It’s not that you have to earn your way in, but you have to show that you’re not going to get in people’s way, cut them off, make them get hurt and that you’re able to look after yourself. Once you’ve shown that you can hang, and this still goes on to this day, these people could become the best friends you’ve ever met in your life.”

‘More than just skateboarding’

It’s that reverence for friendship, freedom and individuality that binds together everyone who spoke to the Courier. They come from three different generations, different towns and different provinces.

Scott Kiborn cuts loose at the China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Scott Kiborn cuts loose at the China Creek skatepark. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

For MacRae, skating is solace. She grew up in foster homes and bounced around numerous locales between Alberta and B.C. before ending up in Vancouver permanently six years ago.

“When you skate, you’re in control,” she said. “I did team sports like soccer, volleyball, basketball and I was a ball hog. I couldn’t cope with the fate of the game being decided by other people. Skateboarding was my thing and if I screw it up, it was always on me.”

Cole’s life is all skate, all day. Between teaching kids how to skate, working at P.D.’s, serving as president of the Vancouver Skateboard Coalition and skating for pleasure, his schedule is pretty full.

He knows a skater when he sees one.

“I meet kids all the time where I think to myself that if we were the same age at the same time, we would have been best friends,” Cole said. “They come in the shop all the time with a burning fire in their eyes. You can see it and you can feel it. They’re skateboarders.”

Little refers to skating as a brotherhood bound by a “magic rolling board.” All of his best friends in life are skaters.

Ditto for P.D. and many of those bonds were forged in a park near Clark.

“Almost every time I’m there, there are one or two kids who are there because they have no place else to be — they’re often times kids who are of an age that they should probably being cared for by someone, but they’re not,” P.D. said. “They’re there caring for themselves. Sometimes some of the China Creek locals are caring for them. China Creek is more than just skateboarding, it’s like an energy vortex.”

Vancouver Skateboard Coalition president Jeff Cole gets some air at China Creek. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Vancouver Skateboard Coalition president Jeff Cole gets some air at China Creek. Photo by Dan Toulgoet/Vancouver Courier

Friday’s celebration at SBC will include photo installations and other historical mementos. The all-ages portion of the proceedings runs from 6 to 9 p.m., followed by a live DJ and beers.

Details are online HERE.