Kim Shattuck and her band the Muffs performed at the Commodore in 2017, playing with the Smugglers. It would be their final show. Photo Paul Clarke

Kim Shattuck and her band the Muffs performed at the Commodore in 2017, playing with the Smugglers. It would be their final show. Photo Paul Clarke

The international underground music community went into collective mourning last week when news emerged Oct. 2 of the death of L.A. rocker Kim Shattuck.

Shattuck had been the lead singer of the beloved band the Muffs for the past 29 years. She died at age 56 after a mostly secret two-year battle with ALS. The Muffs last-ever performance of their long, international career was in Vancouver, playing with my band the Smugglers, at the Commodore Ballroom, May 13, 2017, just a few months before Shattuck’s diagnosis.

For her 35 years in rock ‘n’ roll, Shattuck personified cool. She was the complete package: an excellent singer, guitarist and songwriter who had an inherent knack for melody and hooks. Shattuck was also brazenly confident — a high energy, tall, beautiful and tough front person, usually clad in her signature “baby doll” dresses and thigh-high stockings.

Kim Shattuck personified cool, says Grant Lawrence. Photo Paul Clarke

Kim Shattuck personified cool, says Grant Lawrence. Photo Paul Clarke

Shattuck’s vocal screams were also legendary, introducing her guitar solos and punctuating choruses. And while almost every lead singer has made an attempt at a cool howl, Shattuck’s scream was no question amongst the best ever in rock ‘n’ roll — on the same upper larynx-ripping echelon as Little Richard, the Who’s Roger Daltrey and the Sonics’ Gerry Rosalie.

I knew personally this musical force of nature for 30 years. I consider Shattuck a mentor, a hero and, most importantly, a friend. She took shit from no one. In 1989, when I was still in high school, I snuck into the 86th Street Music Hall to see the Pandoras, a ’60s-style band that Shattuck had been the bassist in since 1985. I was also there to help budding music journalist and high school pal Nardwuar the Human Serviette film an interview.

Back then, Nardwuar had to wait around at the end of the show for a chance to talk to the band. That night, it was Shattuck who was the only willing member to emerge. She proceeded to give a hilariously profane and sexually charged interview during which she flagrantly hit on Nardwuar to the point of propositioning him, to his obvious physical discomfort.

A saucy clip of Shattuck’s interview wound up on my band the Smugglers’ debut single a year later.

After the Pandoras took a horrible turn to glam metal, Shattuck quit to form the Muffs. She wrote to Nardwuar about the new band, which would specialize in major chords and high-energy pop punk — music that swam against the prevailing currents of the emerging grunge era. She sent us a six-song demo cassette, and we flipped out over what we heard.

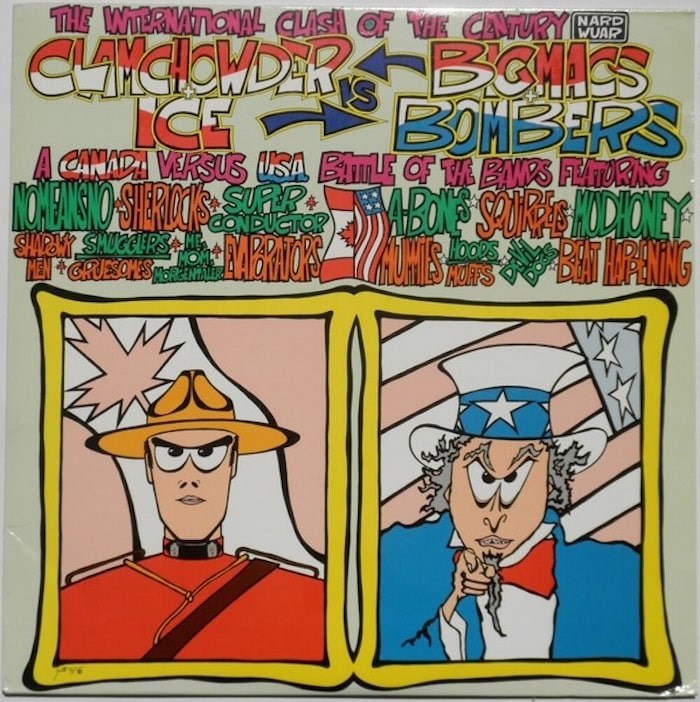

At the time, Nardwuar and I were working on releasing a Canada versus U.S. compilation LP entitled Clam Chowder and Ice versus Big Macs and Bombers. We asked Kim for a Muffs’ track, and to our extreme delight she said yes.

The Canada vs. U.S. compilation LP Clam Chowder and Ice versus Big Macs and Bombers

The Canada vs. U.S. compilation LP Clam Chowder and Ice versus Big Macs and Bombers

“Get Me Out Of Here” became the first Muffs’ song ever to be released to the world, on Nardwuar Records in 1991. The compilation still stands up today, with Canadian contributions from NoMeansNo, Superconductor and the Gruesomes, and American cuts from Mudhoney, the Mummies and Beat Happening.

Later in ’91, the Muffs toured up the West Coast for the first time. In what appears to be a group effort, we booked them a gig at the Cruel Elephant on Granville Street, where they performed alongside Young Youth, a one-off all-star band of Vancouver punks that included bassist Stephen Hamm of Slow, Tankhog and the Evaporators. Hamm has proven to have uncanny knack for being in the right place and the right band for some of Vancouver’s most memorable musical events.

The Muffs were a blur of explosive energy that night, blowing everyone in the small crowd away. They were also a hell of a lot of fun to hang out and party with after the show.

In the short time that followed, the Muffs gained rapid momentum. They released their self-tilted first album in 1993 on Warner Brothers Records, a rare major label debut.

Photo Grant Lawrence

Photo Grant Lawrence

And while it failed to yield any big breakthrough singles, many critics and underground music fans, including myself, consider it a landmark pop-punk record that has stood the test of time. Besides an Angry Samoans cover, Shattuck wrote or co-wrote every song.

The Vancouver connection would pop up a couple years later, again thanks in part to Nardwuar. During a CiTR Radio interview with the Muffs in 1994, after chatting about various bands, affable bassist Ronnie Barnett asked Nardwuar, “What about cub?”

That led to a wild 1995 North American tour with the Muffs and cub, Vancouver’s all female “cuddlecore” sensations, which featured future Grammy nominee Neko Case on drums. The tour was so successful it concluded with Barnett and cub lead singer Lisa Marr eloping in Las Vegas. Marr moved to Los Angeles, and the marriage lasted for eight years.

The friendships between the Muffs and various Vancouver musicians continued to endure for decades. When the Smugglers decided to reunite in 2017, we were totally delighted when the Muffs agreed to play with us at the Commodore Ballroom, along with Chixdiggit and Needles//Pins.

The Muffs delivered in a major way that night, playing fan favourites from their entire catalogue to an adoring, sold out audience, many of whom had flown in for the show from as far away as England, Japan and across North America. No one could have guessed then that it would be the Muffs’ final performance.

In October 2017, Shattuck began noticing she was losing her grip in her left hand. After doctors blamed it on everything from carpal tunnel syndrome to a pinched nerve in her neck, she eventually received the devastating diagnosis of ALS. Both her father and aunt had died from the same disease.

And even though the physical toll happened rapidly, Shattuck and her Muffs bandmates — Barnett on bass and Roy McDonald on drums — managed to create a final album, the band’s seventh. Shattuck was still able to oversee all production and design, and once again wrote all of the songs. “No Holiday” will be released on Oct. 18.

Neither Nardwuar nor I knew she was sick. Few did outside of Shattuck’s closest circle of band mates, family and friends, and that’s the way she wanted it. I was shocked to learn after her death that Shattuck couldn’t move or talk for the last year and a half, because we commonly got in touch online. Despite not being able to type or speak, Shattuck was able to communicate using an incredible device called a Tobii Eye Tracker.

A shot of the Muffs playing a packed Starfish Room on March 21, 1996. Photo Paul Clarke

A shot of the Muffs playing a packed Starfish Room on March 21, 1996. Photo Paul Clarke

According to Barnett, who dated Shattuck at the beginning of the Muffs’ long run, Shattuck handled her fatal diagnosis with grace and humour. And she could still smile right up until the end. She leaves behind her husband of 16 years, a legacy of undeniably great rock ‘n’ roll and a legion of fans from around the world who will never forget the impact of Kim Shattuck.