Two spans of the Second Narrows Bridge sit stuck in Burrard Inlet following the bridge’s collapse during construction on June 17, 1958. Eighteen men died in the collapse and another was killed days later while diving to recover a body. photo supplied North Vancouver Museum and Archives

Two spans of the Second Narrows Bridge sit stuck in Burrard Inlet following the bridge’s collapse during construction on June 17, 1958. Eighteen men died in the collapse and another was killed days later while diving to recover a body. photo supplied North Vancouver Museum and Archives

I crossed a bridge in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001 to save my life. On June 17, 1958, my grandfather died building one.

John Wright is the very last name listed on the plaque honouring those who lost their lives building the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing. I never got to meet him – my mother was only 16 when he was killed.

He loved to read biographies. He was interested in true stories about real people. That’s how he preferred to learn about history.

Eighteen men died that day. One more died a few days later in a recovery dive. I know some true things about one of those men. I know that he was a real person with a real family who has felt his absence at weddings and at births of grandchildren and great-grandchildren with a gnawing sadness and sudden stabs of anger at what he missed out on, and what those kids, including me, missed out on.

He was born in Tisdale, Sask., on Jan. 7, 1918. His father had two boys and a daughter from his first marriage that he brought into his second. His mother’s first child – the fourth of his father’s 11 children – he was pulled out of school in the sixth grade to work trap lines alongside his father in the wilderness of Manitoba. He was 21 when he married my grandmother, Margaret Blanche Hume, 19 at the time. He was 40 when he died. Before his untimely death, he had four children. To support them, he worked as a miner in Flin Flon, Man.; a longshoreman in Port Alberni on Vancouver Island; and an ironworker for Local 97 in Vancouver. “Wright,” a Scottish name, means “worker.” By all accounts, John Alexander (“Jack”) Wright lived up to his name.

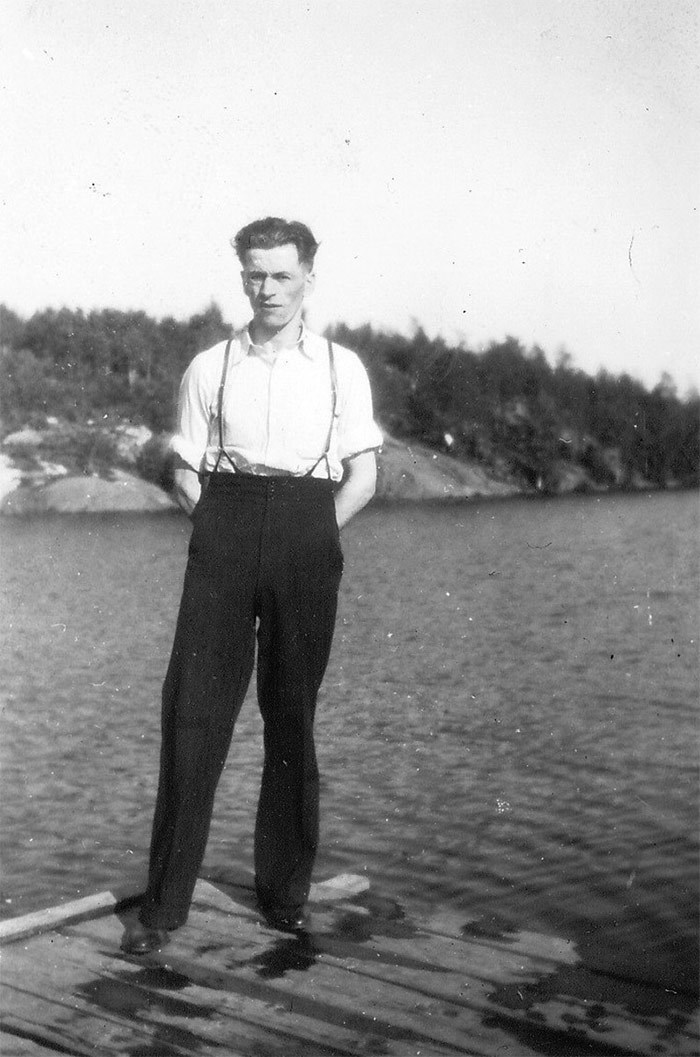

My mother, her sister and her two brothers adored their father. He was a handsome man with a chiselled profile who cut a lean figure from years of hard, physical labour. He’d tell his kids, “Get an education so you don’t have to work with your body like me.”

If he were alive today, he would have turned 100 this year.

John Alexander (“Jack”) Wright was one of the men who died in the fall – photo supplied

John Alexander (“Jack”) Wright was one of the men who died in the fall – photo supplied

For the 19 families, it isn’t grief, but something more permanent, like an empty chair, that has been welded to them and their descendants. Yet each one of the families has done something that the bridge itself could not: over time, we have withstood the unbearable weight that a tragedy of this scale imposes.

Whenever life throws a sucker punch at me, my mother tells me with something etched into her bones: “You’re a survivor.”

I was on my way to work in New York City, three blocks from the World Trade Center, when a plane tore through steel, glass, and human beings on a beautifully clear Tuesday morning. After being trampled and nearly suffocating in a toxic cloud of debris, I ran over the Brooklyn Bridge as it swayed under the weight of those fleeing the grinding crush of a collapsing skyscraper. It was the bridge that brought me home to Brooklyn – covered from head to toe in ashes, but home.

It was almost quitting time when the Second Narrows went down at 3:40 p.m. on a warm and sunny Tuesday afternoon in Vancouver. In a little home in nearby Burnaby, my mother set her father’s plate at the head of the dinner table. It wasn’t until 8:45 that night when they learned that his name was included on the list of the dead. A business agent named Norm, the same man who had secured the job for my grandfather, came to the house, but my grandfather’s brother Art had already broken the news to the family.

Widowed with four children, my grandmother never remarried. As a kid, I remember her telling us that she wasn’t interested in finding another man – Jack Wright had been the love of her life.

This real man, this true man.

Once, he was working on the Agassiz Bridge. He was living in a bunkhouse, but he’d come home on the weekends. The Fraser River was rising, so the men were told to get their cars to higher ground. My grandfather’s car was leading the procession, but it got stuck in a hole. As the water flooded the Agassiz and took his car, he crawled onto its roof. Eventually, he was lifted out by a crane. He drove all the way home to Burnaby in a rigged apple crate. Later, always the resourceful one, he removed the car’s seats and dried them out for reuse.

He wouldn’t let my mother date anyone who drove a car until she was 16. To get around this rule, she would have her dates drop her off a block away from home. She remembers that time when a car was driving slowly behind her while she was walking the one block home, and later found out it had been her father. She doesn’t remember if he grounded her or not, but she remembers what he told her: “It’s easier to tell the truth, even if you’re in trouble.”

This real man, this true man.

And if you want to know how he treated his wife, his daughter will tell you that he was very loving and protective. He’d wash his own work clothes because they were too heavy for my grandmother to lift. Her knees were bad, so he would get down on the hardwood floors and scrub them when they needed it.

He was the unifier of his family who always got relatives together for picnics and dinners. Family was everything to him.

He was a quiet man. He wasn’t a big drinker, but after a few rum and cokes, he livened up a party, and he loved to dance. My mother remembers him waltzing with her mother, and “he was good,” she says.

New Westminster didn’t have enough spaces in its Little League, so when the Burnaby boys were denied access, their parents formed their own league. My grandfather was the league’s manager, my grandmother its player agent, my mother and her sister were scorekeepers, and their two brothers were players. A boy that my grandfather had benched for being a hothead later organized the entire league, dressed in uniform, as honour guard at my grandfather’s funeral.

True story: my mother married a man with the surname “Bruckman,” which means “bridge man” or “toll taker” in German. So I was born into this name, and this story, and it will always be who I am.

I met a survivor at the 57th bridge memorial in 2015. He told me, “I knew your grandfather. He was a good man. You should be proud of him.”

There were 19 men who lost their lives. Jack Wright was one of them. Pulled out of school in the sixth grade, he liked to learn about history by reading biographies. He liked true stories. He liked stories about real people.

Cynthia Bruckman is a writer currently living in Victoria, B.C. You can read more about her at cynthiabruckman.com.